Ancient 'Cockroaches of the Sea' Fossilized While Playing 'Follow the Leader'

The trilobites go marching one by one, hurrah, hurrah … well, at least they did, some 480 million years ago.

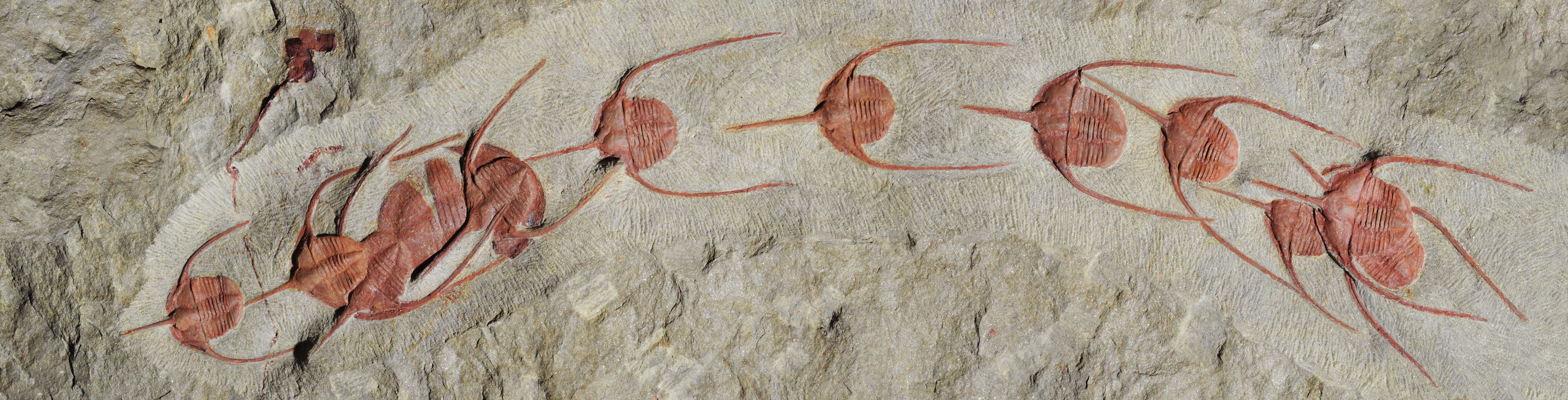

New fossils from Morocco show lines of trilobites in orderly queues, likely buried by a storm as they trekked from one place to another under the Ordovician seas in an ancient game of "follow the leader."

"I think people think that collective behavior is something new in the course of evolution, but actually sophisticated behavior started very, very early," said study leader Jean Vannier, a paleontologist at the University of Lyon in France.

Related: Photos: Trove of Marine Fossils Discovered in Morocco

Trilobites all in a row

Vannier and colleagues from Marrakech, Morocco, discovered the trilobites in the southern part of Morocco in an area known for well-preserved fossils of animals from the early Ordovician, a geologic period that began about 485 million years ago and is one of six periods that make up the Paleozoic era. The Ordovician is famous for its diverse marine life, from primitive fish to corals to undersea scorpions the size of human beings. Trilobites — arthropods that looked a bit like cockroaches — also scuttled around the Ordovician seafloor or swam through its oceans. These resilient creatures first evolved during the period before the Ordivician, the Cambrian, and survived two mass extinctions (one at the end of the Ordovician, about 444 million years ago, and one at the end of the Devonian, about 360 million years ago). Trilobites didn't disappear until 252 million years ago, when a mass extinction at the end of the Permian period wiped out 95% of all species on Earth.

Not much is known about how trilobites behaved, but some fossil evidence hints that they didn't swim or burrow solo. Paleontologists have found clusters of fossilized trilobites, apparently gathered in large groups to molt their exoskeletons or to mate.

Related: Image Gallery: Cambrian Creatures: Primitive Sea Life

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new Moroccan fossils were striking because the trilobites were cleanly arranged in lines and obviously hadn't floated into position after death, Vannier said: The animals were all facing the same direction, often touching each other with the spiny projections from their bodies. Their single-file arrangement is reminiscent of the migration of the modern-day spiny lobster, Vannier told Live Science. These Caribbean creatures queue up in lines to march to quiet waters during stormy months, resting their antennae on one another as they move.

Acting collectively

The rocks around the trilobite fossils showed evidence of repeated, rapid storm deposits, Vannier and his colleagues reported today (Oct. 17) in the journal Scientific Reports. The lined-up trilobites were probably buried instantly by an avalanche of sediment, possibly accompanied by the stirring-up of oxygen-poor waters that helped suffocate the animals rapidly. The fossils record no sign of a struggle in death; whatever took their lives didn't even disrupt the trilobites' careful queue.

Similar trilobite queuing has been found fossilized in younger rocks, Vannier said, and fossils from southern France show the same species (Ampyx priscus) lined up. The trilobites were blind, so they may have used their projecting spines to keep track of each other as they moved.

"It seems to be a normal behavior of this species in different parts of the world," Vannier said.

Trilobites aren't the only ancient animals that seem to have behaved collectively. Shrimp-like creatures called Synophalos from the Cambrian period 520 million years ago have been found fossilized in long chains in China. Scientists suspect they were migrating as a group. And horseshoe crabs, which first appeared on the scene 450 million years ago, still gather on shorelines today to breed under the cover of darkness.

- These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

- Photos: 508-Million-Year-Old Bristly Worm Looked Like a Kitchen Brush

- Photos: 'Naked' Ancient Worm Hunted with Spiny Arms

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.