We finally know how trilobites mated, thanks to new fossils

A single fossil revealed the claspers.

Trilobites may not look like cuddly creatures, but come mating time, one species of these now-extinct arthropods — which looked like giant, swimming potato bugs wearing Darth Vader helmets — would come together for a little hug, a new study finds.

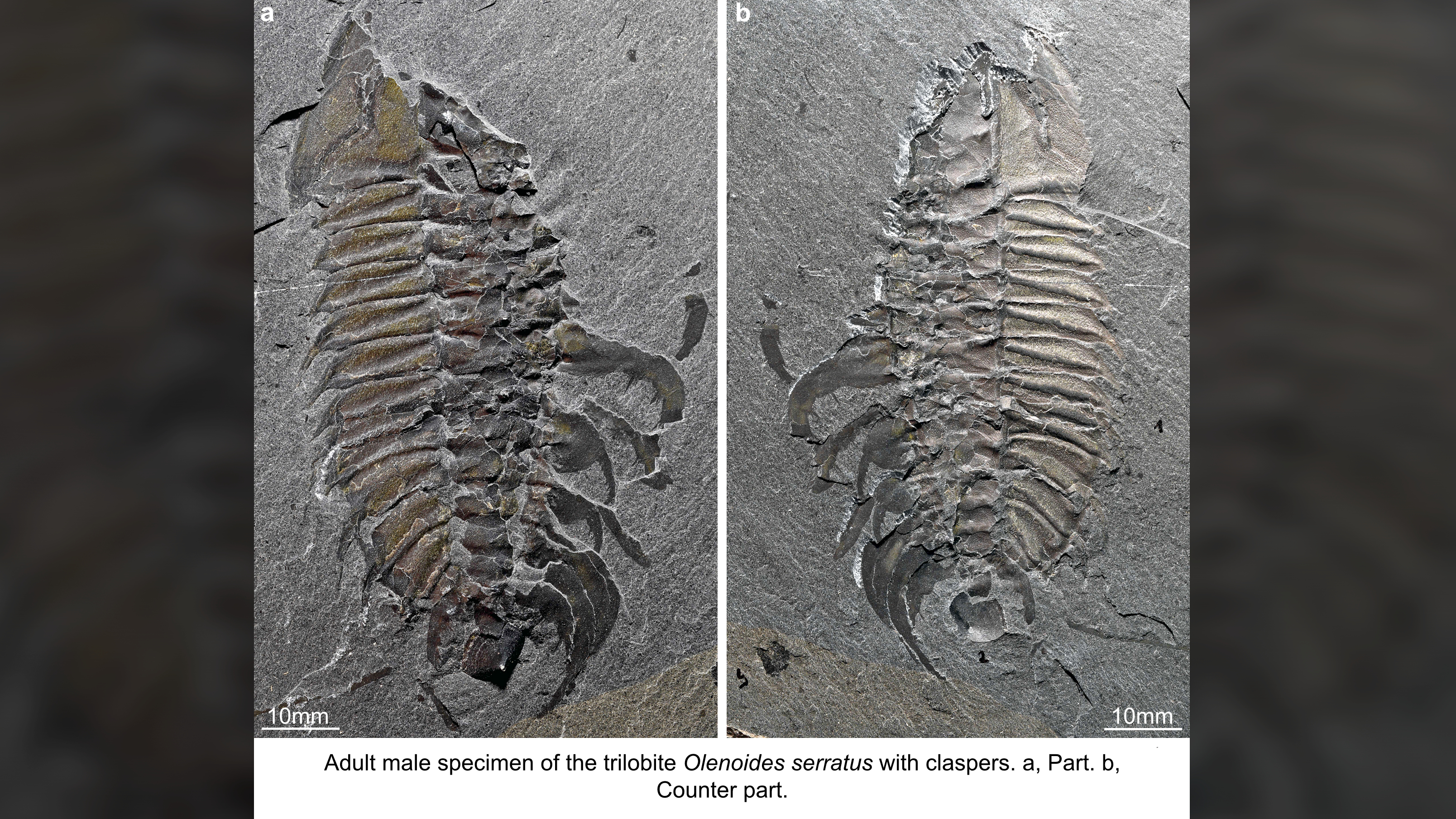

A scientist made this discovery after coming across an extraordinary fossil of Olenoides serratus, a trilobite species that lived about 508 million years ago during the Cambrian period. This well-preserved fossil revealed a pair of short appendages on the underside of its midsection, which were likely used as claspers, the researchers said. A female O. serratus probably stationed herself on the seafloor, and then a male would mount her from above, using the claspers to hold onto her body — a maneuver that would put him in the best possible mating position.

"The importance of holding onto the female is so the male is in the right position when the eggs are released," study lead researcher Sarah Losso, a doctoral candidate of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard University, told Live Science. "Because that increases the chances that his sperm will fertilize the eggs. It's a behavior that will increase the likelihood of successful mating."

Related: Why did trilobites go extinct?

There are more than 20,000 known species of trilobites that inhabited Earth for about 270 million years, until they went extinct around 252 million years ago at the end of the Permian period. Researchers have known about this species, O. serratus, for more than a century, after paleontologists found its fossil remains in the Burgess Shale, a fossil hotspot for Cambrian sea creatures located in what is now the Canadian Rockies.

Scientists have mostly focused on O. serratus specimens found in the early 1900s, meaning they have largely ignored additional specimens found at the turn of the 21st century, Losso said. However, while embarking on a big project to examine this beastie, Losso found a prized fossil at the Royal Ontario Museum.

"I had to look at every single specimen, so I came across this one and was like, 'That is weird. That's not what these appendages are supposed to look like at all,'" she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Trilobite fossils rarely preserve the creatures' legs; typically, only the hard outer shell fossilizes, Losso said. In fact, only 38 of the 20,000 known species have fossils with preserved appendages, she said. So, it's remarkable that this particular specimen preserved the shorter appendage pair at the midsection, she said.

"It's already a cool trilobite just because it has appendages at all," she said.

This unusual leg pair is narrower and shorter than the leg pairs in front and behind it, she said. What's more, these short appendages don't have spines — a hallmark on the trilobite's other legs that likely helped the predator shred its food.

So, why would a trilobite have a pair of short, slender and spineless appendages at its midsection? To investigate, Losso and study co-researcher Javier Ortega-Hernández, an assistant professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard University, compared O. serratus' appendages with those of living arthropods, a group that includes many modern invertebrates, including insects, spiders and crabs.

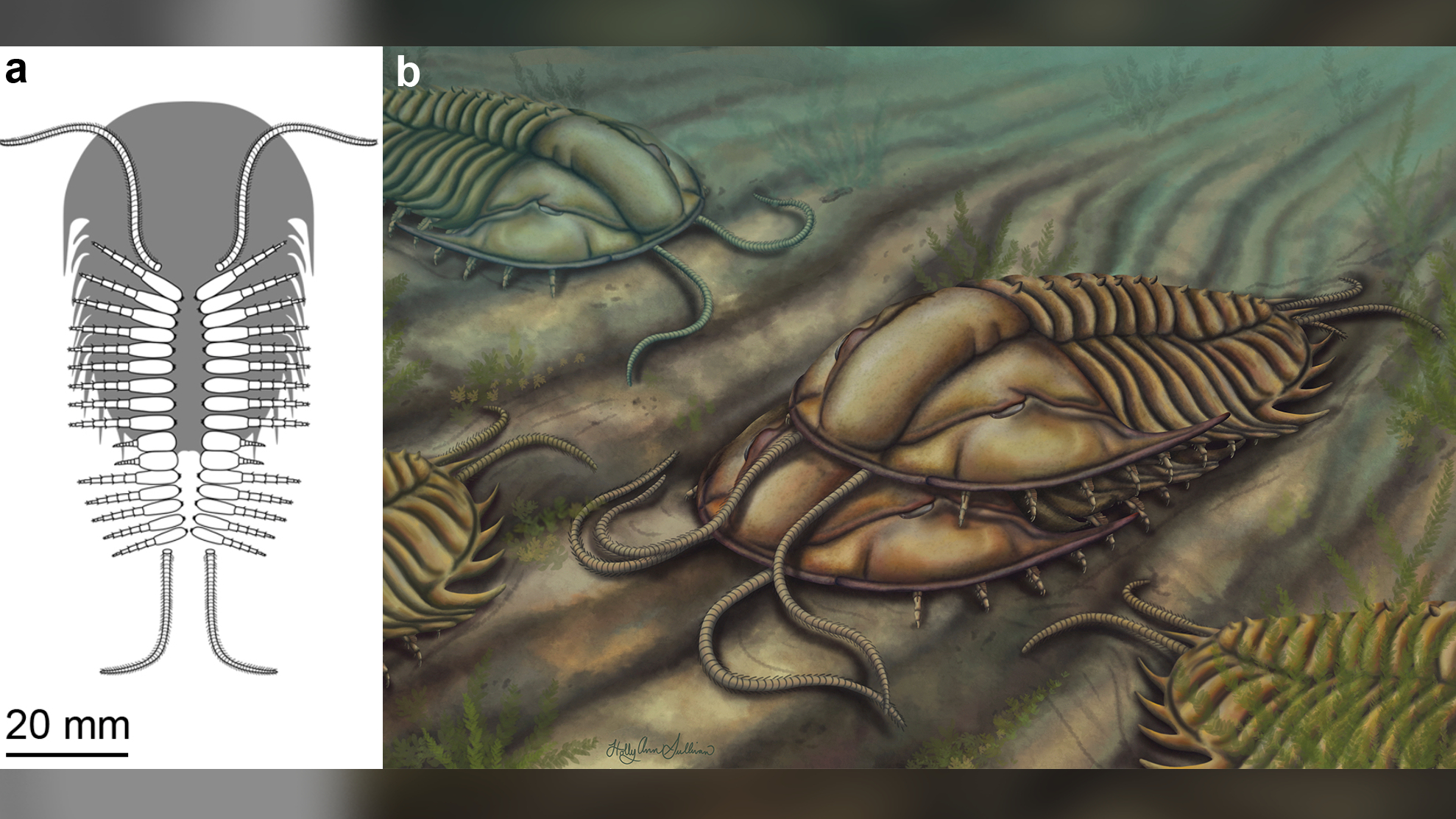

This analysis revealed that O. serratus' weird appendages were likely claspers, Losso said. During a mating session, it's likely that the male would go on top of the female, with his head lining up with the female's trunk, "so he's offset more toward the back, but on top of her," Losso said. "In this position on the exoskeleton, there are these spines that project off of the tail. The appendages of the male would line up well with those spines, so the claspers could grab onto those two pairs of spines."

Put another way, the males likely used their claspers to "hold onto the spines of her tail," Lasso said.

Another well-preserved O. serratus specimen "definitely does not have claspers," Lasso said. "We think that is likely [a] female." In other words, this species likely had sexual dimorphism, meaning that the males and females had different characteristics.

This "claspers mating strategy" is seen today in horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus), which are very distantly related to trilobites.

"In horseshoe crabs, they actually get pretty violent about this; Males will shove each other off," Lasso said. "You might get multiple males all holding onto one female. The males end up hurting each other and sometimes they rip off appendages because they're all jostling for a position to be in that spot [on the female] when eggs are released."

Related: What is the largest arachnid to ever live?

It's possible that O. serratus was equally competitive about mating, she said. But she cautioned against extrapolating this behavior to other trilobite species, as these creatures had a wide array of habitats and body shapes.

"This is the first time we're seeing [a] really significant specialization of appendages in trilobites," Lasso said. "It's interesting to see that complex mating behavior had already evolved in arthropods by the mid-Cambrian."

The study makes "a convincing case that the modified legs … are real biological variation, and not regeneration after being damaged," Greg Edgecombe, a researcher of arthropod evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science in an email. "Their shape makes sense if the specimen is a male and these specialized legs are used to hold on to a female during mating."

Earlier studies provided some evidence that trilobites reproduced like horseshoe crabs "because clusters of trilobites of the same species of the same (adult) size have long been known," Edgecombe added. "The idea was that they came together as a group to molt their exoskeletons and then mate. Now, we can add the detail that at least some trilobite males had claspers."

The study was published online Friday (May 6) in the journal Geology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.