Famous T. rex had a bone infection, new medical scans reveal

The T. rex, named Tristan Otto, has a distinctive mass on its jaw bone.

A Tyrannosaurus rex that perished some 68 million years ago was just diagnosed with a bone infection in its jaw, new research finds.

The T. rex fossil was originally discovered in 2010 by commercial paleontologist Craig Pfister, who excavated the bones from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana; the skeleton contains 170 jet black bones, including 50 skull bones, making it one of the most complete T. rex skeletons ever found. After being jointly bought by two collectors, who named the dinosaur Tristan Otto after their sons, the fossilized skeleton was lent to the Natural History Museum in Berlin, Germany, where it stands to this day, according to the museum's website.

And recently, Dr. Charlie Hamm, a radiologist at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin, and his colleagues got a chance to zap this famous fossil with X-rays.

Related: Image gallery: The life of T. rex

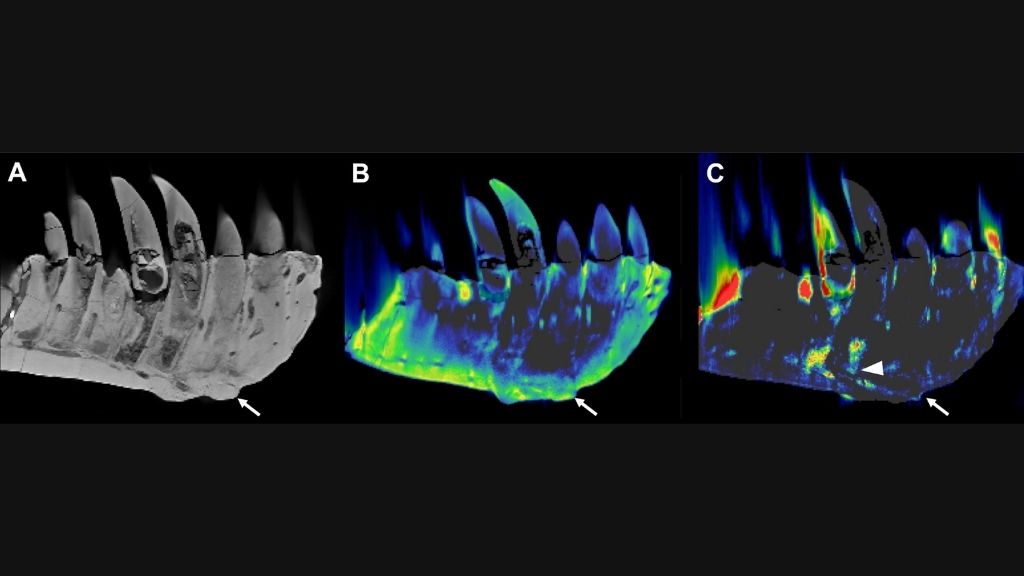

The team used a medical imaging technique called dual-energy computed tomography (DECT), which is a type of CT scan. Standard CT scans deploy X-rays at a target from different angles, and taken together, these individual snapshots can be compiled to generate a virtual 3D image. DECT works similarly to standard CT but uses X-rays of two different energy levels.

Each chemical element absorbs a different fraction of an X-ray beam at each energy level, according to a 2010 report in the journal RadioGraphics. So by applying DECT to Tristan Otto, the researchers gathered detailed information about the chemical composition of the dinosaur's bones. This would not be possible with a typical, single-energy CT scan, which only provides information about tissue density, Hamm told Live Science.

"To our knowledge, this is the first time that we were able to really implement this method on fossils," he said. Previously, Hamm and his colleagues used a standard CT scan to examine Sue, the famous T. rex fossil housed at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Those scans revealed that Sue had chronic osteomyelitis, a persistent bone infection, according to a 2020 study in the journal Scientific Reports. But until now, no one has reported scanning a fossil with DECT, Hamm said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team scanned a large portion of Tristan Otto's lower left jaw, which measured 31.3 inches (79.5 centimeters) long and had a maximum thickness of 3.2 inches (8.1 cm), they wrote in an abstract. To do so, they carefully placed the bone in a protective box and then slid that box into a CT scanner. The team was particularly interested in examining a tumor-like mass on the surface of the bone that extends into the root of one of the tyrannosaur's teeth, Hamm said.

Their scans revealed that this lumpy mass contains a high concentration of the element fluorine, compared with the surrounding bone. The abundance of fluorine hinted that this region of bone was significantly less dense than the surrounding tissues at the time of Tristan Otto's death, Hamm said.

Related: Photos: Newfound tyrannosaur had nearly 3-inch-long teeth

That's because, as part of the fossilization process, groundwater containing fluorine would have penetrated the dinosaur's bones and transformed a bone-borne mineral called hydroxyapatite into fluorapatite, which is more chemically stable. So in regions of the bones that were less dense, possibly due to an ongoing infection, more fluorine would have seeped into the bone tissue and thus remain preserved in the resulting fossil, Hamm said. Based on this analysis, the team diagnosed Tristan Otto with tumefactive osteomyelitis, a bone infection that can drive the development of tumor-like masses.

The team presented their new research today (Dec. 1) at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. As a continuation of the proof-of-concept study, they've already begun scanning additional fossils at the Natural History Museum in Berlin; looking forward, the team plans to hone the imaging technique so that it might be applied to many more fossils around the world.

DECT could offer scientists a simple way to examine the chemical composition of fossils without damaging them, and could also help researchers spot fossils while they're still trapped within samples of sediment, Hamm said.

"This is really the first kind of glimpse of what might be possible," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.