China gets 'mixed report card' in its coronavirus response. How will the US do?

Now that the new coronavirus is expected to spread across the United States, many people are wondering whether the country is up for the challenge.

The first U.S. death linked to the coronavirus was reported in Washington state over the weekend, where officials say up to 1,500 people may have been infected, The New York Times reported. A rising number of cases with unknown origin are being reported in the U.S., indicating community spread to individuals who haven't traveled to affected areas, or been in contact with those who have.

In China, where the virus originated, government officials have put about a half billion people on partial or total lockdown, built two new hospitals with a combined total of 2,600 beds in 12 days and deployed 40,000 health care workers from other parts of China to help fight the outbreak in Wuhan.

So, how is China faring, overall, and how might the U.S. stack up?

Related: Live updates on COVID-19

China's report card

China has handled the outbreak admirably in some regards, but poorly in others, so it gets "a mixed report card," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious-diseases specialist at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee.

Schaffner gave China's scientists an A+ for discovering that the mystery illness was caused by a novel coronavirus, sequencing its genome "in record time" and sharing that data with the world, he told Live Science. But the country earned a C- on sharing epidemiological data on the disease, such as the number of ill people and their clinical symptoms. "They changed their case definitions [the criteria used for diagnosing the disease], and people just didn't have confidence in the data that they were reporting," Schaffner said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He gave China another C- for delaying work with the World Health Organization (WHO) and ignoring an offer of partnership from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); those organizations hoped to work with China "on behalf of their own people and the world's population to help to find the nature of the problem," Schaffner said.

But China gets an A for "instituting the largest public health experiment in the history of humankind, which is the quarantine of Wuhan [city] in Hubei province," Schaffner said. "Nobody has ever tried that before." He awarded China another A+ for successfully implementing the quarantine.

Or, as a Feb. 24 report that China and the WHO collaborated on put it, "In the face of a previously unknown virus, China has rolled out perhaps the most ambitious, agile and aggressive disease containment effort in history."

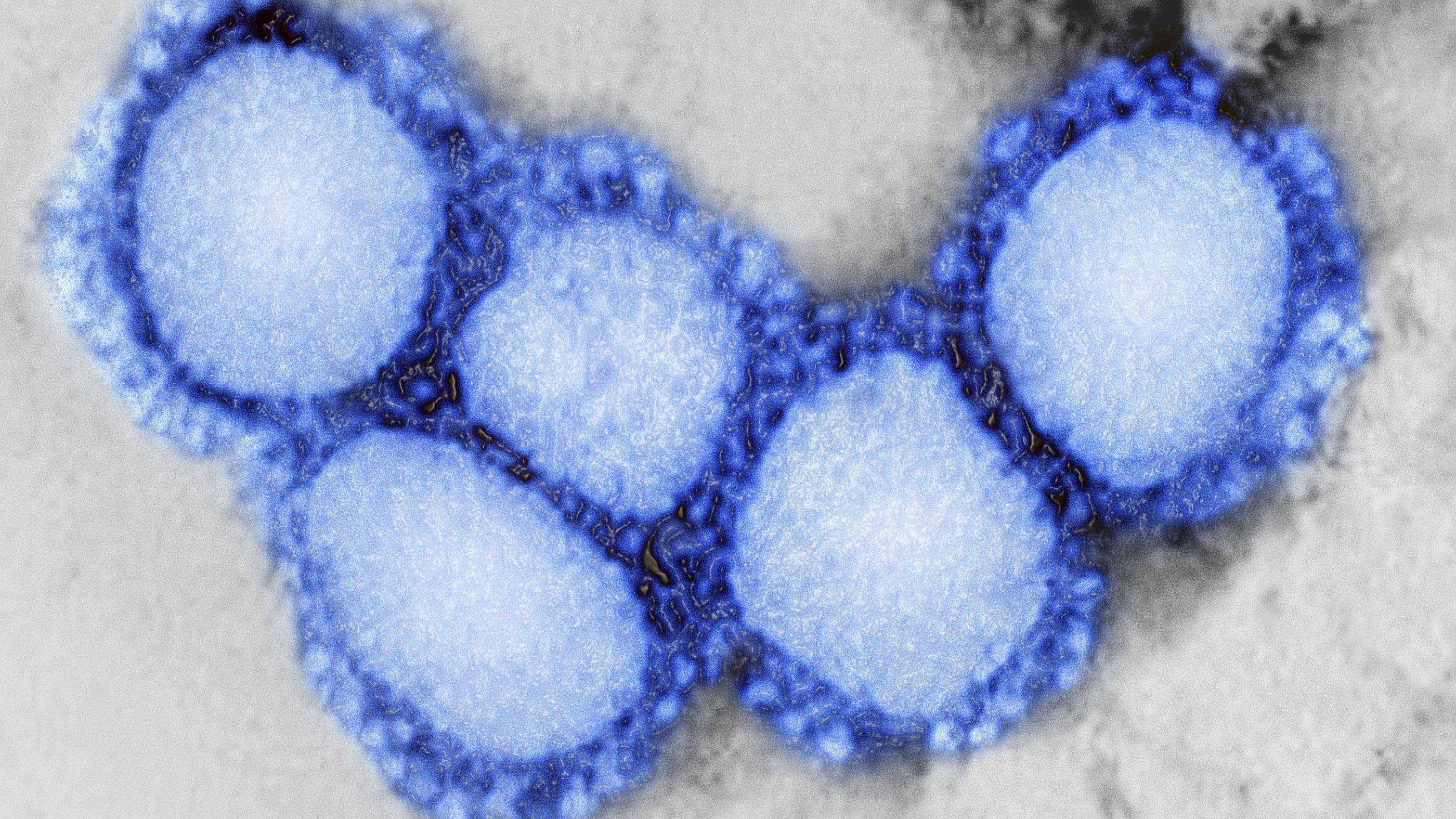

It's difficult, however, to see how effective the quarantine is because China hasn't consistently studied the virus' spread among subpopulations, so Schaffner gave them a B- in that regard. According to a Feb. 28 opinion piece in the journal JAMA, "it appears that the strict measures China took may have 'bought the world some time' but did not prevent the global dissemination of SARS-CoV-2," the virus that causes the disease COVID-19.

Meanwhile, China gets a B for treating people with SARS-CoV-2. "They were swamped and they struggled with that, and of course they set up all kinds of ancillary facilities," he said. "You have to give them some extra points."

Even though it's a mixed report card, Schaffner said China's response to the virus was "impressive" given the circumstances. But "they still have lessons to learn on transparency, communication and international cooperation," he said.

How will the U.S. fare?

The United States has the opportunity to do well, so long as medical services are made available and the government issues clear and science-based directives to help stem the spread of SARS-Cov-2, experts told Live Science.

Related: Going viral: 6 new findings about viruses

"I think that our challenge is not so much scientific or operational, because I do think we do have a lot of expertise, capability and capacity in this regard," said Eric McNulty, associate director at the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative at Harvard University. "The real challenge of whether we're up for the task is going to come down to the challenge of leadership."

In a place that's as large and diverse as the United States, it's essential that those involved with the response "have abundant coordination, cooperation, collaboration and communication," the four C's of disaster response, said McNulty, who is also an instructor at the Harvard School of Public Health.

It would be a mistake to downplay the seriousness of the virus or to make it into a political issue, which may happen given that it's an election year, McNulty noted.

Government leaders can issue fact-based guidelines so that businesses, organizations, schools and individuals can make informed decisions about how to protect themselves and others, McNulty said. While a China-like quarantine likely wouldn't happen here — the closest comparison would be the voluntary shutdown that happened in Boston during the 2013 manhunt for the marathon bombers; as with the marathon bombing, a good information campaign could do wonders to protect the public from the coronavirus, McNulty said.

For instance, if a sick person is self-quarantining but needs groceries, a campaign could highlight the best practice for getting supplies while limiting exposure, like by going to the store late at night and using self-checkout.

The government would also be wise to note that scientists are constantly learning new facts about the virus, so people won't be surprised if guidelines change, McNulty said.

If the virus spreads throughout the U.S., "I think we are up to the task," said Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. "But I think it's important, at this point, that we engage in larger-scale testing in order to get a better gauge on the prevalence [of the virus] in the community."

On Saturday (Feb. 29), the FDA announced it would give several certified labs and hospitals across the U.S. the green light for using test kits.

However, because up until just a few days ago, only the CDC lab had testing capabilities and the CDC only approved testing for those with travel to certain areas (or contact with those people), there is a backlog of cases at the CDC and many cases were likely missed — meaning those individuals were unknowingly spreading the virus.

Glatter added that "more aggressive immigration enforcement will drive people underground, [and make them] less likely to go to the hospital for testing and evaluation for COVID-19." Plus, people who are underinsured or don't have insurance might be hesitant to seek care, which highlights the need for an accurate, rapid and affordable test, he said.

"I think we, like every other nation, will struggle," Schaffner said. "It's going to be akin to an influenza pandemic outbreak."

- The 9 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 27 devastating infectious diseases

- 11 surprising facts about the respiratory system

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.