Does UV light kill the new coronavirus?

Ultraviolet light has been used to stop pathogens in their tracks for decades. But does it work against SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the pandemic?

The short answer is yes. But it takes the right kind of UV in the right dosage, a complex operation that is best administered by trained professionals. In other words, many at-home UV-light devices claiming to kill SARS-CoV-2 likely aren't a safe bet.

UV radiation can be classified into three types based on wavelength: UVA, UVB and UVC. Nearly all the UV radiation that reaches Earth is UVA, because most of UVB and all of UVC light is absorbed by the ozone layer, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And it's UVC, which has the shortest wavelength and the highest energy, that can act as a disinfectant.

Related: What is ultraviolet light?

"UVC has been used for years, it's not new," Indermeet Kohli, a physicist who studies photomedicine in dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, told Live Science. UVC at a specific wavelength, 254 nanometers, has been successfully used to inactivate H1N1 influenza and other coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory virus (SARS-CoV) and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), she said. A study published June 26 to the preprint database medRxiv from Kohli's colleagues awaiting peer review now confirms that UVC also eliminates SARS-CoV-2.

UVC-254 works because this wavelength causes lesions in DNA and RNA. Enough exposure to UVC-254 damages the DNA and RNA so that they can't replicate, effectively killing or inactivating a microorganism or virus.

"The data that backs up this technology, the ease of use, and the non-contact nature" of UVC make it a valuable tool amid the pandemic, Kohli said. But responsible, accurate use is critical. UVC's DNA-damaging capabilities make it extremely dangerous to human skin and eyes, Kohli said. She cautioned that UVC disinfection technologies should primarily be left to medical facilities and evaluated for safety and efficacy by teams with expertise in photomedicine and photobiology.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When it comes to a-home UVC lamps, their ability to damage skin and eyes isn't the only danger, Dr. Jacob Scott, a research physician in the Department of Translational Hematology and Oncology Research at Cleveland Clinic, said. These devices also have low quality control, which means there's no guarantee that you're actually eliminating the pathogen, he said.

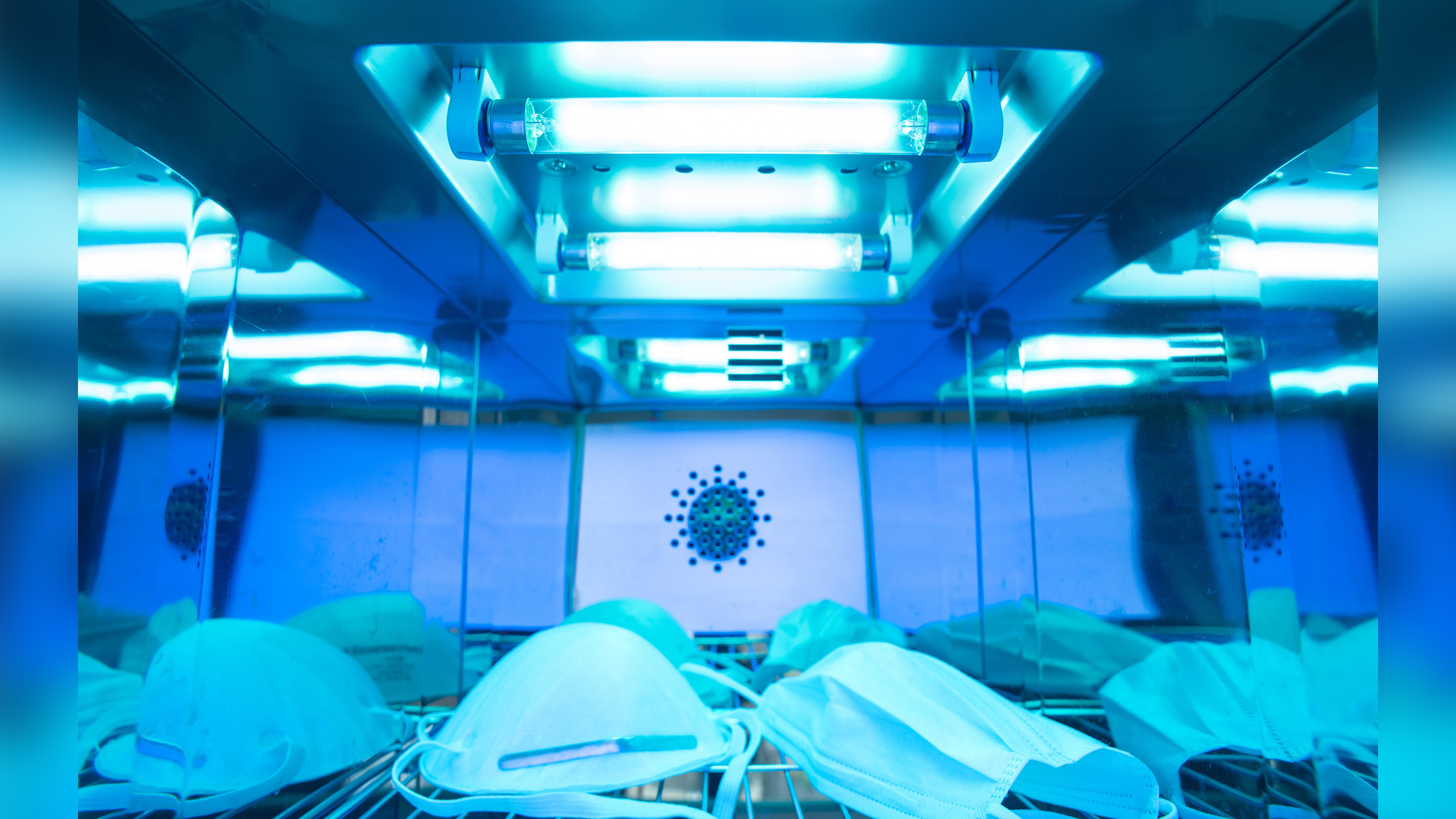

"UVC does kill the virus, period, but the issue is you have to get enough dose," Scott told Live Science. "Particularly, for N95 masks, which are porous, it takes a pretty big dose" of UVC-254 nm to eliminate SARS-CoV-2. This kind of accuracy isn't possible with at-home devices.

In hospitals, the geometry of the room, shadowing, timing and the type of material or object being disinfected are all accounted for when experts determine the right dosage of UVC needed to kill pathogens. But that kind of "quality assurance is really hard out in the world, out in the wild," Scott said. At-home devices don't offer that kind of precision, so using them could offer a false assurance that SARS-CoV-2 has been eliminated when it hasn't, he noted. "Having something you think is clean, but it's not, is worse than something that you know is dirty" because it affects your behavior toward that object, he said.

Both Kohli and Scott and their teams are working to make UVC disinfection of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as face masks and N95 respirators, more efficient. Kohli's group advises hospitals and vendors repurposing existing UVC equipment for N95 respirator decontamination. Scott's group developed a machine that can be used by smaller medical facilities and a software program that helps users factor in the geometry of the disinfection room so that staff can deliver the most effective dose of UVC.

There are ongoing conversations in the field about installing UVC units in ceilings to decontaminate circulating air, Kohli said. And others are researching another wavelength of UVC called UVC-222 or Far-UVC, which may not damage human cells, she added. But that will require more research, Kohli said. Still, it's clear that "used accurately and responsibly, UVC has enormous potential."

Originally published on Live Science.

Donavyn Coffey is a Kentucky-based health and environment journalist reporting on healthcare, food systems and anything you can CRISPR. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired UK, Popular Science and Youth Today, among others. Donavyn was a Fulbright Fellow to Denmark where she studied molecular nutrition and food policy. She holds a bachelor's degree in biotechnology from the University of Kentucky and master's degrees in food technology from Aarhus University and journalism from New York University.