No, this dinosaur isn't vaping. It just breathed like a weirdo.

A well-preserved fossil is a "missing puzzle piece" for the evolution of dinosaur respiration.

A new illustration of a dinosaur exhaling a puffy cloud might look like the animal is vaping. But in reality, the artwork is simply depicting a dinosaur breathing on a chilly morning. And it turns out this dino breathed in a way unlike any seen in this group of dinosaurs before.

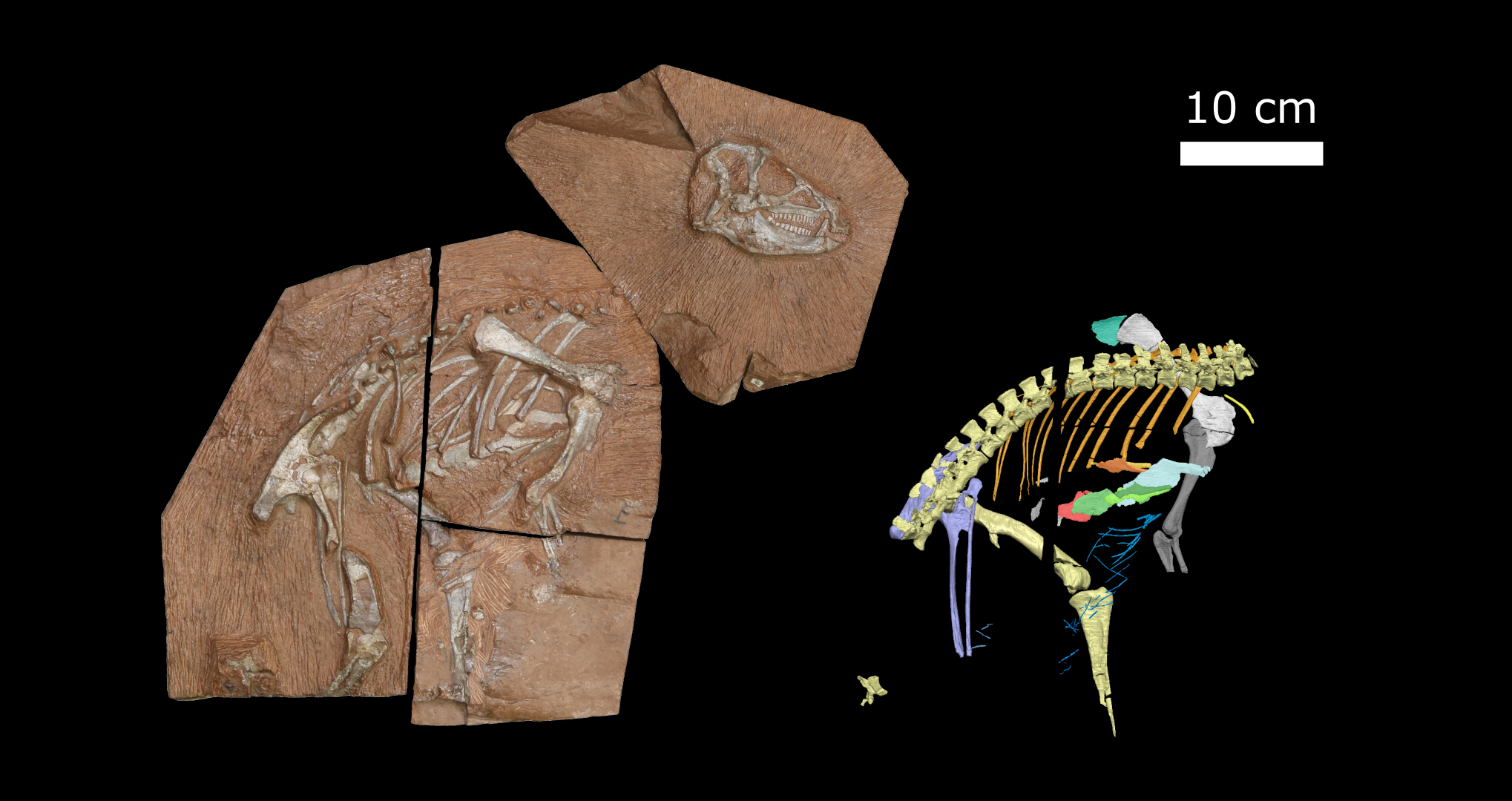

Scientists found unusual rib and sternum bones in an exceptionally well-preserved fossil skeleton of Heterodontosaurus tucki, a turkey-size, plant-eating ornithischian, or bird-hipped dinosaur — the group that includes duck-billed dinosaurs, frilled dinosaurs like Triceratops and armored dinosaurs like Ankylosaurus.

X-rays of the fossil, which was discovered in South Africa's Eastern Cape in 2009, enabled researchers to digitally reconstruct the skeleton in 3D. Their models revealed skeletal features that were previously unknown in ornithischians, showing rib and hip bones that were connected by muscles to help the animal breathe in a way that was novel for dinosaurs: through expansion of its chest and belly.

Related: 7 surprising dinosaur facts

H. tucki measured about 3 feet (1 meter) from nose to tail and roamed what is now South Africa about 200 million years ago during the early Jurassic period (200 million to 145 million years ago), according to the Natural History Museum in London. It's one of the earliest species to be included in the ornithischian group, which means that H. tucki can provide clues about the evolution of features that are common among ornithischians but differ from other dinosaurs, researchers reported July 6 in the journal eLife.

Because the H. tucki skeleton was nearly complete, paleontologists discovered a group of tiny, slender abdominal rib bones called gastralia. These rib bones are found in crocodiles and other modern reptiles and play a part in respiration, but were previously unknown in ornithischian dinosaurs, said lead study author Viktor Radermacher, a doctoral student in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

"Gastralia were thought to be absent from all ornithischians, but we show that they retained them for a very brief period of their early evolution," Radermacher told Live Science in an email. H. tucki also had paddle-shaped ribs and elongated breastbone plates, which could move with ribs that were attached to the sternum to facilitate breathing. Such features "are lost in later ornithischians," Radermacher said. This tells us that early members of this group "were doing something very different with their bodies," he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mammals breathe by expanding and contracting their lungs with the help of an organ called a diaphragm, which pushes air in and out. Birds — a modern lineage of theropod dinosaurs — use a different method, in which a network of air sacs distributes oxygen by running it in a loop through the birds' lungs and bodies. Paleontologists who previously reconstructed extinct dinosaurs' internal anatomy found evidence of similar air sacs, suggesting that most dinosaurs breathed like modern birds, Live Science reported in 2005.

But H. tucki's anatomy suggested that this dinosaur had a different strategy. By flexing muscles connecting the gastralia and the pelvis, and the sternal plates and bony paddles, the dinosaur would have inhaled air by inflating its belly and chest, and then relaxed those muscles to push air out, according to the new study.

This type of breathing resembles the respiration of certain reptiles; crocodiles breathe using their chests, bellies, "and truly weird muscles" in their bodies, while lizards breathe by expanding and contracting their entire bodies "and even the neck sometimes," Radermacher said. Pterosaurs, which are flying reptile cousins of dinosaurs, have some bony chest features resembling those of H. tucki, hinting that pterosaurs may also have breathed with their chests and bellies, he added. (Pterosaurs, crocodylians and dinosaurs all belong to the archosaur group).

Prior to this discovery, some scientists suspected that ornithischians might have breathed differently from other dinosaurs; this well-preserved H. tucki specimen "was the missing piece of the puzzle" for confirming that hypothesis, Radermacher said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.