Venus and a newly discovered comet will cross paths in December. Will sparks fly?

If a meteor shower falls on Venus and no one sees it, does it still make a flash?

Venus is Earth's twisted twin in so many ways, what about on the skywatching front?

Alas, stargazing isn't great from the Venusian surface: The thick carbon-dioxide atmosphere that blankets the planet means there's no catching a break in the clouds. But above those clouds — where, come to think of it, conditions are rather less lethal for human stargazers anyway — the view of the night sky might be pretty similar to that on Earth.

A skywatching session on Venus would require being, say, 35 to 40 miles (55 to 60 kilometers) above the surface, where the temperature and pressure are surprisingly Earthlike, Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis who focuses on Venus, told Space.com.

"It is the only other place in the solar system where room temperature and pressure conditions are present and, potentially, an astronaut could stand on the railing of a gondola with a breathing apparatus on but otherwise in shirtsleeves," he said. Perhaps the stars would twinkle a little differently or the atmosphere would tinge meteors a different color, but the gist would be the same, he predicted.

Related: Amazing photos of Comet NEOWISE from the Earth and space

Let's stick with meteor showers, since plenty of skywatchers are fresh off that terrestrial experience, thanks to August's stunning Perseid meteor shower.

As long as you're above the clouds, Byrne said, if the planet swings through the necessary debris, a meteor shower should work more or less the same way on Venus as it does on Earth. "At that point and above, presumably it would be similar to watching a meteor shower at sea level on Earth," he said. "I cannot think of any reasons why you would not see shooting star streaks as stuff burns up."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Perseids are caused by Earth plowing through a trail of dust shed by the Comet Swift-Tuttle. Comets are notoriously messy objects, the cosmic equivalent of Pig-Pen in the Peanuts comics, scattering dust wherever they go. And most meteor showers are caused by the same short-orbiting comet leaving a trail of debris along the path it takes, lap after lap through the solar system.

But there's a second, much rarer type of meteor shower that relies on just one pass of a long-period comet, one that treks through the solar system on a path so long the icy lump will never retrace its steps during a human lifetime. Trickier might be an understatement: Earthling skywatchers have never caught a meteor shower caused by fresh debris from a long-period comet, at least not according to existing records. Theoretically, since the two planets orbit the sun at similar distances, the same long odds hold for Venus, despite the abysmal lack of skywatching records from that world.

But implausible doesn't mean impossible, and if this scenario were ever to unfold in our lifetimes, the best chance of it happening may come this December.

Meet Comet Leonard

In December, Venus and a long-period comet called Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) will nearly cross paths, with the planet crossing the comet's debris trail just three days after the icy body dashes by Venus on its first visit to the inner solar system in some 80,000 years.

"There's a lot of unknowns here that could affect things a lot," Qicheng Zhang, a planetary science graduate student at Caltech and lead author of a new paper exploring the scenario, told Space.com. "The chances aren't particularly good for observing this event, but it's not out of the realm of possibility and it wouldn't be completely surprising if something ends up being observed."

Zhang is fascinated by comets for their brightness and unpredictability, so every day he checks a list of newly discovered comet candidates to see what scientists have spotted. In January, he stumbled on an announcement for Comet Leonard, which immediately stood out to him.

"I'm interested in those comets that pass fairly close to the sun," Zhang said. "This one didn't pass super close to the sun, but it still got closer than Earth's orbit, which is more interesting than most comets that are discovered these days." So, Zhang took a closer look at Comet Leonard to see how its path aligned with the sun and the inner planets.

"The one thing that stood out was that the comet's orbit and Venus' orbit almost perfectly intersect," Zhang said. Their orbits come within 31,000 miles (50,000 km), equivalent to the distance from Earth to the ring of geosynchronous satellites orbiting high above our heads. The bodies themselves will come within 2.7 million miles (4.3 million km) of each other on Dec. 18; the next day, Venus will cross the comet's trail three days behind the icy body.

But Comet Leonard is making just one pass and hasn't built up such a clear path of debris, so Zhang wanted to determine whether its rubble might be substantial enough to trigger a meteor shower on Venus come the December intersection — and, if it would, whether there was any possibility humans could somehow observe it.

The research is described in a paper posted on July 26 to the preprint server arXiv.org and submitted to the Astronomical Journal.

A Venusian meteor shower?

According to Zhang and his colleagues' calculations, the most promising scenario for an observable meteor shower as Venus intersects the comet's trail would require high levels of activity on the icy body when it was at the very least 30 times the average distance of Earth from the sun (or about the distance of Neptune), perhaps more like 100. That's not impossible, but it is rare, and would mean that Comet Leonard was coated in particularly volatile ices, prone to turn to vapor under still quite frigid conditions.

For a display dramatic enough for scientists on Earth to spot the fireworks on Venus, according to Zhang's calculations, that activity would need to have begun at a distance from the sun more like 500 or even 1,000 times that of Earth.

"That's really far away, and well before the comet was discovered. We don't know if the comet was actually even active at that distance," he said. "If we did have a positive detection of meteors on Venus from this event, it would tell us that this comet was quite active at high distances from the sun."

And not much about the comet's swing through the solar system itself can improve the odds. "The only thing that could possibly change or add meteors to the shower from now on is if there were to be a highly explosive outburst of the sort that very few comets in history have produced," Zhang said. "That's not something that you would normally expect to see in a comet and would be highly unusual" — more unusual than spotting meteors on Venus, even.

That means it's all unlikely — but still possible.

Extraterrestrial shooting stars

If Comet Leonard does trigger a meteor shower that humans can manage to observe, it wouldn't be the first such data from beyond Earth.

In October 2014, a comet dubbed Siding Spring swung past Mars, with the Red Planet plowing through the comet's dust trail about three hours later. The meteors fell on the side of Mars facing away from Earth, but NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft picked up the fleeting signature of magnesium that the comet debris dumped into the Red Planet's upper atmosphere.

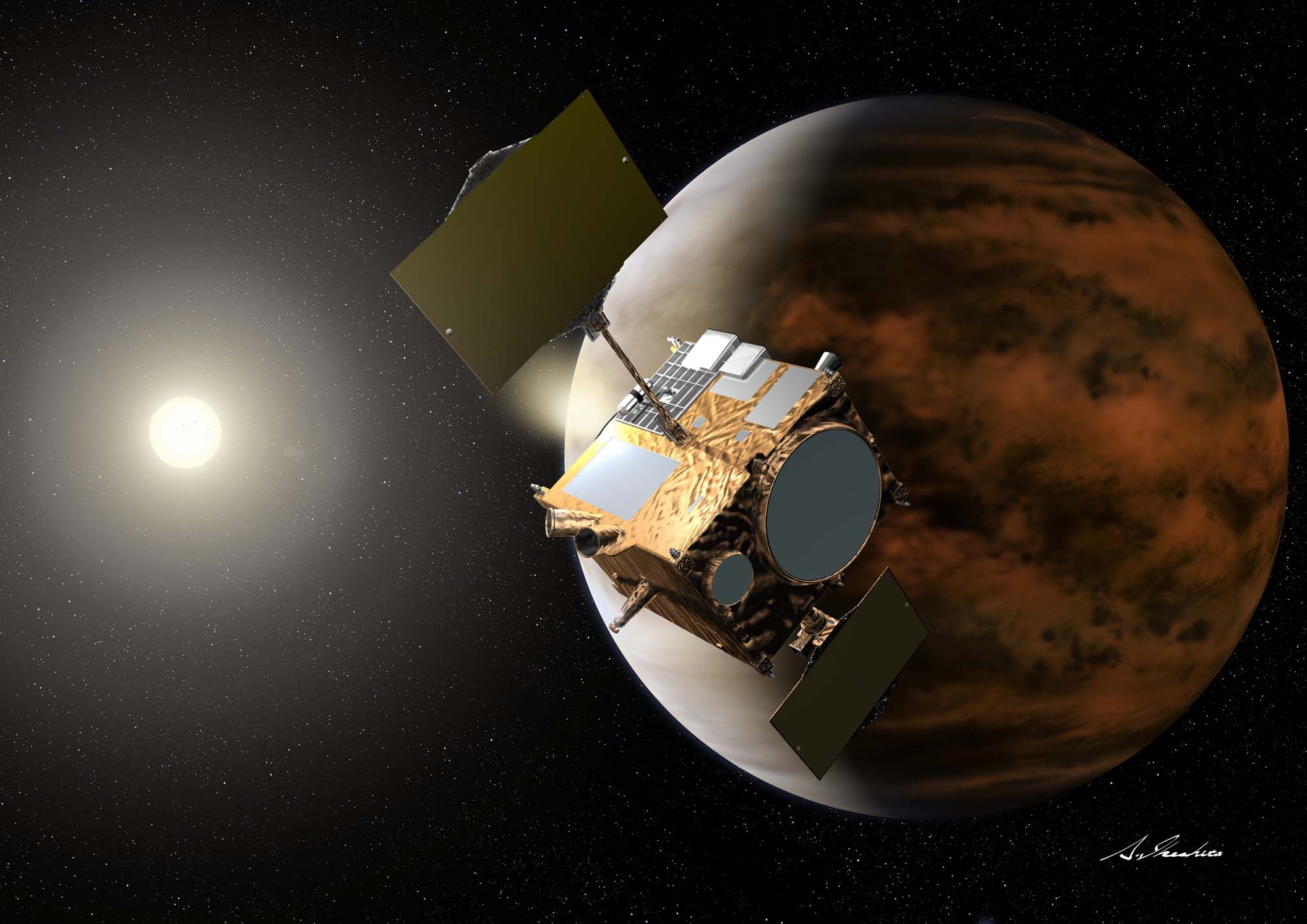

Siding Spring's encounter with Mars doesn't make for an easy comparison with this December's potential fireworks at Venus. Comet Leonard will never come as close to Venus as its predecessor did to Mars, and Venus hosts only one orbiter, Japan's Akatsuki spacecraft, unlike the four orbiters and two rovers that were stationed at the Red Planet in 2014, according to NASA.

But Earth, Venus and the sun will be oriented such that observers on Earth may be able to catch faint flashes from Comet Leonard's debris, Zhang noted, which was impossible during Comet Siding Spring's encounter. "There was never a chance to see any Martian meteor shower from Earth," he said.

"Venus will be much closer to Earth than Mars was, and so there's the possibility that maybe if there were something interesting," — remarkably large meteors born of cometary activity at huge distances from the sun, for example — "that could potentially in theory be visible from Earth by fairly small, even advanced-amateur class telescopes," he said. (The Hubble Space Telescope won't be able to attempt observations because Venus will be too close in the sky to the sun at the time.)

And although Zhang isn't holding his breath for an impressive display, if the encounter does produce a spectacle, it could produce the same sort of metallic traces in Venus' atmosphere as Comet Siding Spring did at Mars.

"Our uncertainties can't rule out that there could be a very large meteor storm, a large impressive meteor storm the sort that would be needed to generate a meteor layer of the sort that appeared on Mars," Zhang said. "That's still a possibility, but a much smaller possibility than a very small meteor shower."

Once in a lifetime

Chances are, neither Comet Leonard nor any other will have a similar opportunity to make its mark on Venus within our lifetimes.

Such close cometary flybys of the inner planets are unusual, Zhang noted. "Probably this event has a recurrence time scale frequency on the order of maybe once every few centuries or so per planet," he said. "It's a fairly rare event, as far as comet close encounters go."

And whatever happens at Venus, Zhang said, Comet Leonard is on its last pass through the solar system. The sun's heat may shred the icy body, a risk comets always take during their excursions.

If it doesn't, Zhang and his team calculated that the rest of the solar system will jostle the comet's orbit enough that this time around, Comet Leonard will slip away from our neighborhood and end up stranded in interstellar space.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.