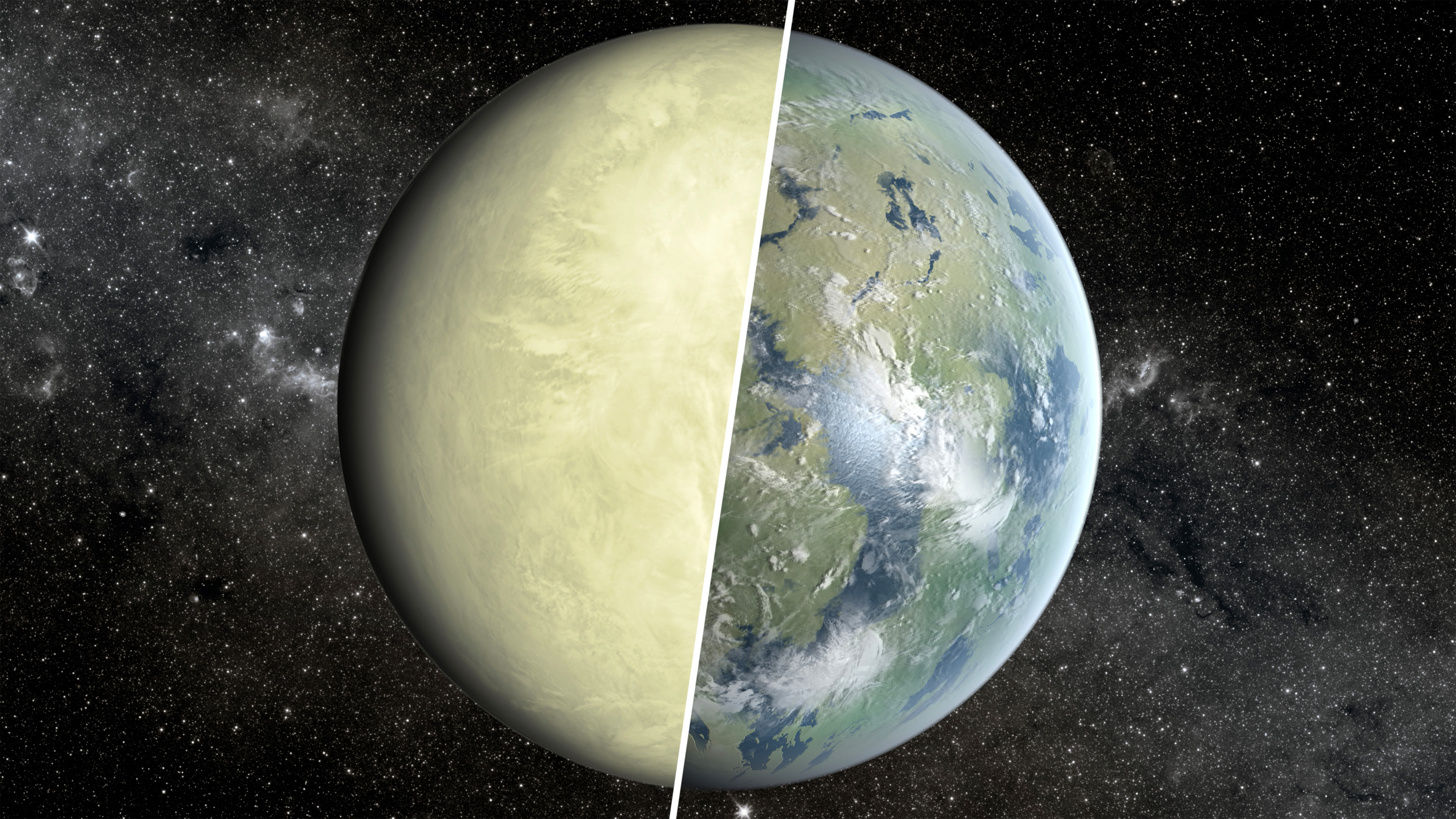

Venus, once billed as Earth's twin, is a hothouse (and a tantalizing target in the search for life)

As Earth's sister planet, Venus has endured a love-hate relationship when it comes to exploration. Now, new results suggest the presence of a signal of potential habitability on Venus, and the long-forgotten sibling may find itself back in the spotlight.

With its orbit near the rising or setting sun, Venus shone clearly to the first ancient astronomers. As humanity began to explore the solar system, a world with nearly the same mass and radius as Earth seemed like the most promising target. Venus sits on the border of our sun's habitable zone, the region around a star where a planet should be able to host liquid water on its surface, and ideas of a veritable twin planet swam before the eyes of scientists and the public alike.

Related: Venus clouds join shortlist of places to search for alien life

More: The greatest mysteries of Venus

"Ideas of a temperate or jungle-style environment at the Venus surface persisted until the mid-60s," Stephen Kane, a planet-hunter at the University of California, Riverside, told Space.com by email. He noted that "Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet," the last Hollywood movie to feature astronauts visiting Venus, came out in 1965, the same year the Soviet Venera 3 probe launched, bound to crash-land on the planet. In the movie, the fictional astronauts landing in 2020 encountered a swampland filled with dinosaurs, a very different environment from the Venus scientists know today.

When NASA's Mariner 5 flew by Venus in 1967, it revealed a surface temperature of 860 degrees Fahrenheit (460 degrees Celsius). "The swamps digitally evaporated before their eyes," Suzanne Smrekar of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California told Space.com by email. Smrekar is the principal investigator of NASA's proposed VERITAS mission to Venus. (The name is short for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy.)

No longer a swampy sister, our vision of Venus became a hellish world with thick clouds, losing much of the attention it had previously garnered in science-fiction lore. With a surface hot enough to melt lead, the planet was too broiling to host water on its surface. Its potential for life seemed to evaporate with the swamps.

But while the fickle public turned its eyes toward the redder world of Mars, scientists continued to study Earth's twin. "We started the task of trying to understand how the surface of Venus could be so far removed from previous ideas," Kane said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the past 50 years, humans have tried to solve that puzzle. The Soviet Union continued to send Venera missions to Venus until the early 1980s, some to orbit the world and others to land on its surface. NASA's Viking and Pioneer missions blew by, snapping photos and collecting data on their way to the outskirts of the solar system.

In 1990, NASA's Magellan mission mapped the surface of the planet and the European Space Agency's Venus Express orbited the world for eight long years, studying its atmosphere. In 2015, Japan's Akatsuki mission began a probe of the Venusian atmosphere that continues today. Meanwhile, missions across the solar system regularly use Venus as a gravitational boost to distant worlds, taking a few brief observations on their way past.

The myriad observations, along with advances made in understanding how planets evolve, have presented a slowly changing picture of Venus. The results may help to resolve questions about the evolution of life.

"Although the realization during the '60s regarding the hellish conditions of Venus caused many to believe that Venus has nothing to do with habitability, we have since changed our perspective to understand that Venus has everything to do with habitability," Kane said.

Earth's future, Earth's past

During the initial phases of exploration, scientists quickly realized that Venus was suffering a severe case of the greenhouse effect. The planet's thick atmosphere worked as a blanket to trap heat, raising the temperatures to unbearable extremes.

"Many people assumed Venus was a 'solved problem,' where a runaway greenhouse scenario had run amuck and that was the end of the story," Kane said. "However, we're realizing now that it is only the beginning."

The conditions that once led scientists to suspect Venus could be an Earth-like world hadn't changed. Both planets appear to have the same origins: rocky worlds large enough to hold onto their atmospheres with initial conditions ripe to collect water on the surface. So where did Venus go wrong?

That's a question that still plagues Venus researchers as they seek to determine the conditions that lead to habitability and those that lead to an overheated catastrophe. Close behind is the question of whether the Venusian atmosphere changed dramatically in a single catastrophe or whether it was a slow change over time.

Ongoing observations have also revealed that Venus is anything but inactive. Low-resolution radar images of the surface have shown evidence for recent explosive volcanism, within the past 100 million years. If our twin planet continues to belch gases into the air through its peaks, that would argue for a slow shift in the atmosphere rather than a single cataclysm.

These questions are especially relevant for Earth, where human-produced greenhouse gases continue to build up in the atmosphere. Some point to Venus as a sign of our planet's future if human behavior doesn't change.

But the planet next door may not only reveal our future, it may also show our past. According to Smrekar, Venus is the only place in the solar system that may have continents and subduction, the first step in kicking off plate tectonics. Despite an apparently long list of missions that have toured the planet, however, our view of the surface remains tantalizingly scanty. If Venus does have continents, planetary scientists want to know when and how they formed, which could help researchers to better understand early Earth.

"Earth's continents and system of plate tectonics have shaped the evolution of Earth's climate and habitability," Smrekar said. "But they came into existence billions of years ago; little data from that time remains."

It's even possible that it was Venus, not Earth, where life first appeared in the solar system. According to Smrekar, our twin planet has many of the characteristics required for a habitable world — an internal geologic engine to drive volcanism, tectonics, surface weathering, and even a potential ocean in the past. "Even though its surface appears supremely inhospitable today, in the past it may have been the first habitable planet," she said.

The exoplanet next door

As the number of known exoplanets climbs into the thousands, Venus may be the key to unlocking and understanding which of those worlds are habitable. Planets around other stars are viewed from an incredible distance, and it is unlikely that humans will step on any of them in the near future. But from a distance, a potentially habitable exo-Earth looks just like an exo-Venus.

"If viewed as exoplanets, Venus and Earth are identical," Smrekar said. "Yet they are entirely different today."

In 2015, Kane established a "Venus zone," the region around a star where a planet's atmosphere could devolve into a greenhouse world. At the time, he said that he wanted to emphasize that size alone, one of the primary methods of characterizing a world as "Earth-like," is not enough to indicate habitability.

Sorting out the hellish Venus-like worlds requires knowing what made Venus into the planet it is today. "The key to understanding planetary habitability and how it evolves with time resides in understanding the evolution of our sister planet," Kane said.

That's one reason scientists like Smrekar and Kane advocate for another mission to Venus. Further exploration could hunt for signs that water existed on the surface relatively recently, which could indicate the planet slowly lost its habitable state rather than suffering from a quick catastrophe.

"We absolutely must go back to Venus in order to answer the many outstanding questions, especially related to when Venus lost its liquid water," Kane said.

Kane adds that Venus can help provide better insight into the evolution of life on other worlds than other non-Earth terrestrial planets in the solar system.

"The topic of habitability in the context of exoplanets will always focus on Earth and Venus-size planets, not Mars-size," Kane said. "The quest for detecting life in the universe necessarily requires understanding the incredible Venus-Earth dichotomy."

New results

After decades of being ignored, Venus may soon be taking center stage.

New results, released Monday (Sept. 14), reveal the presence of a potentially biological signal that could come from life hidden in the planet's clouds. The clouds of Earth’s twin have long been considered a potential home to life, but the discovery of phosphine, a flammable gas that, on Earth, can come from the breakdown of organic material, gives the topic new urgency.

"Biology in the atmosphere could be the last surviving members of a prior Venusian biosphere," Kane said. "If confirmed as being the result of life in the clouds, this result would be an extraordinary lesson in how life can really adapt to all available riches within an environment."

But Kane did issue a few caveats for that conclusion. If life currently lives in the clouds of Venus, it must have found a way to continue to linger in the atmosphere rather than falling back to the planet's surface, which he calls "a difficult problem to solve." While life has been discovered in the clouds of Earth, that material has been lofted upward from the surface through convection, as hotter and less dense material moved upward. That mechanism doesn't exist on Venus, Kane said.

Additionally, the atmosphere of Venus is hot, dry, and surrounded by large reservoirs of sulfuric acid, all of which can make it difficult for life to have survived the past billion years, from the time when the surface may have once hosted life, Kane said. And the new research is based on phosphine production on Earth, while the surface and atmosphere of Venus are significantly different.

Smrekar agreed.

She thinks that the new results highlight the need to look for active and recent volcanism. While the authors dismissed active volcanism as an explanation for their detection, she points out that the process is difficult to observe on Venus, where the signal of lava can disappear within days or weeks. Understanding surface chemistry and the processes that produce volcanism is key to interpreting the new research, which she said "is intriguing and highlights the need to understand our sister planet better."

For Kane, the new results underscore the need to return to Earth's twin in the near future.

"Since the claim has been made and we don't currently have a good explanation for the observations, we have a responsibility to investigate further and determine what the true source of the phosphine is," he said. He pointed to upcoming missions, including VERITAS, that will help scientists understand the atmosphere and geology of the planet.

"It is through these kinds of missions that we will be able to fully answer this question of possible life in the Venusian clouds," Kane said.

Follow Nola on Facebook and on Twitter at @NolaTRedd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.