Voluptuous 'Venus' of the Ice Age originated in Italy

The famed figurine is approximately 30,000 years old.

An ancient carved statue of a very full-figured woman, known as the Venus of Willendorf, originated far from where it was found in the early 20th century, in Willendorf, Austria. Scientists recently peered inside the voluptuous Ice Age figure for the first time since its discovery and found clues that helped them trace the origins of the stone to a location hundreds of miles away, in northern Italy.

The statue, which measures just 4.3 inches (11 centimeters) tall, dates to about 30,000 years ago during the Paleolithic period (2.6 million to 10,000 years ago). An Ice Age artisan would have carved the figure with flint tools, and researchers with the Natural History Museum of Vienna (NMW) excavated the ochre-painted carving from a bank on the Danube River on Aug. 7, 1908, according to the museum's website.

Related: Back to the Stone Age: 17 key milestones in Paleolithic life

Though small, the Venus statue is highly detailed, representing "a symbolized adult and faceless female with exaggerated genitalia, pronounced haunches, a protruding belly, heavy breasts, and a sophisticated headdress or hairdo," researchers wrote in a new study, published Feb. 28 in the journal Scientific Reports. In fact, archaeologists who discovered the statue named it after a deity of love, because at the time they presumed that ancient female statues with prominent sexual features were surely fertility goddesses.

It was the statuette's raw material rather than its representational detail that intrigued the scientists. It was carved from oolitic limestone, a type of sedimentary rock made of spherical grains cemented together, according to the Kansas Geological Survey. However, there are no oolitic limestone deposits for at least 124 miles (200 kilometers) around Willendorf, according to the study.

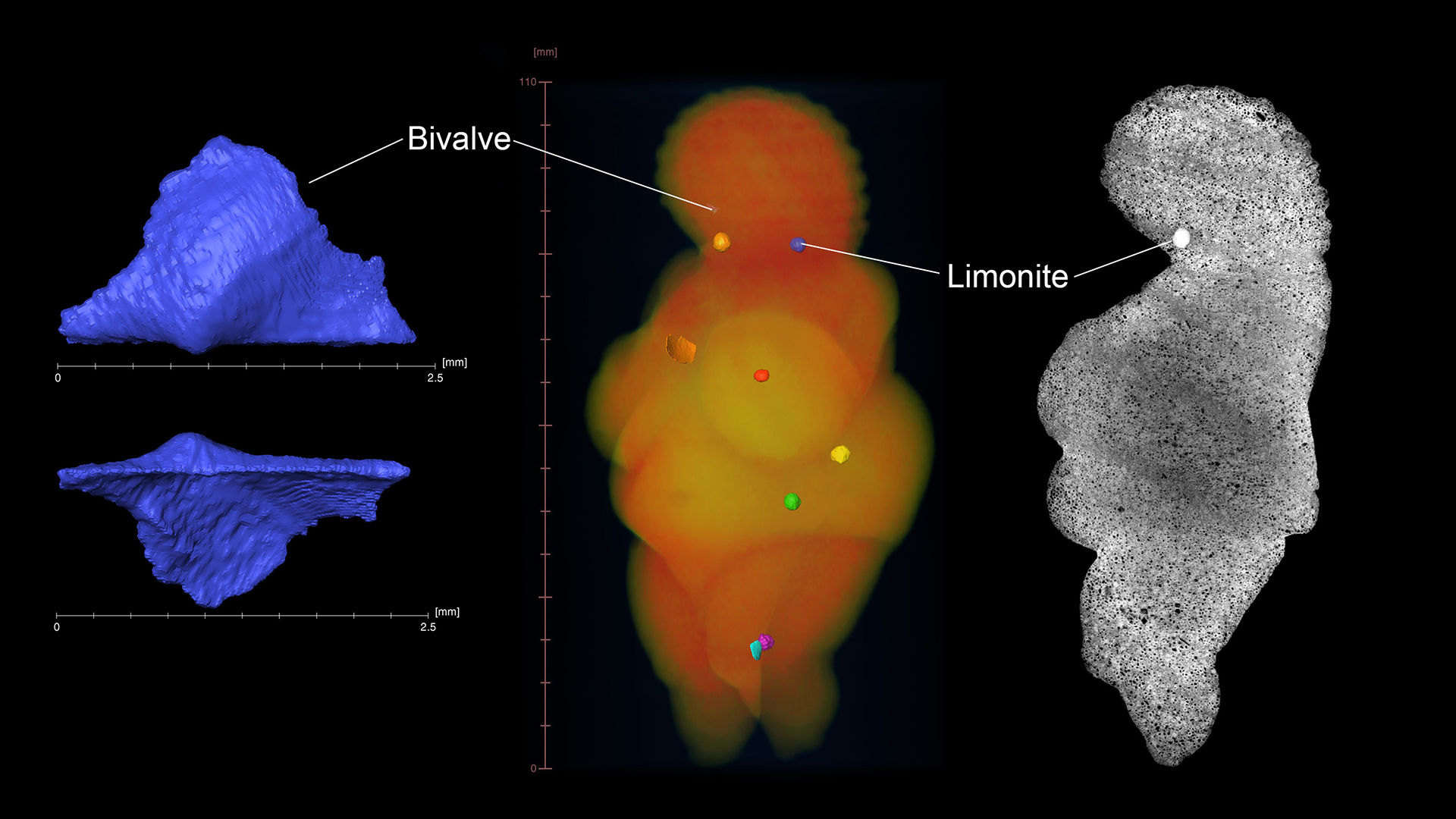

As one of the oldest examples of figurative sculpture, the Venus figure is considered too rare and valuable to risk investigating it with invasive methods. But micro-computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans offered scientists a chance to noninvasively examine sediments and particles inside the statue. They looked at the clumps of ooid spheres in the limestone, comparing them with clusters from similar oolitic limestone deposits that were sampled from locations across Europe: from France to the Ukraine and Crimea in the east, and from Germany to as far south as Sicily. Limestone samples from Saga de Ala, a site in northern Italy's Lake Garda valley, were "virtually indistinguishable" from the Venus limestone, suggesting "a very high probability for the raw material to come from south of the Alps," the scientists wrote in the study.

Their scans also showed that Venus' rocky interior contained fragments of tiny bivalve fossils, which the scientists identified as belonging to the genus Oxytomidae. That placed the age of the stone between 251 million and 66 million years old, when that now-extinct genus was alive. Oolite limestone from northern Italy likewise held bivalve fragments, the researchers reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

How then did the carved figure wind up hundreds of miles from northern Italy? The Willendorf Venus is associated with people in the Gravettian culture, which emerged about 30,000 years ago and was distributed across Europe. While it's impossible to tell when the limestone was collected and when the figure was carved and brought from the Alps to the Danube, the journey may have spanned generations and suggests that Gravettian hunter-gatherers were highly mobile, according to the study.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.