Modern humans lived in eastern Africa 38,000 years earlier than thought

The remains were buried under a massive layer of soot from a gigantic volcanic eruption.

Modern humans emerged in eastern Africa at least 38,000 years earlier than scientists previously thought. That conclusion was drawn from traces of a colossal volcanic eruption used to date the earliest undisputed Homo sapiens fossils.

The remains, dubbed Omo I, were discovered at the Omo Kibish site near Ethiopia's Omo river in the 1960s. Previous estimates dated the human fossils to around 195,000 years old. Now, new research published Jan. 12 in the journal Nature, tells a different story — the remains are older than a colossal volcanic eruption that rocked the region roughly 233,000 years ago.

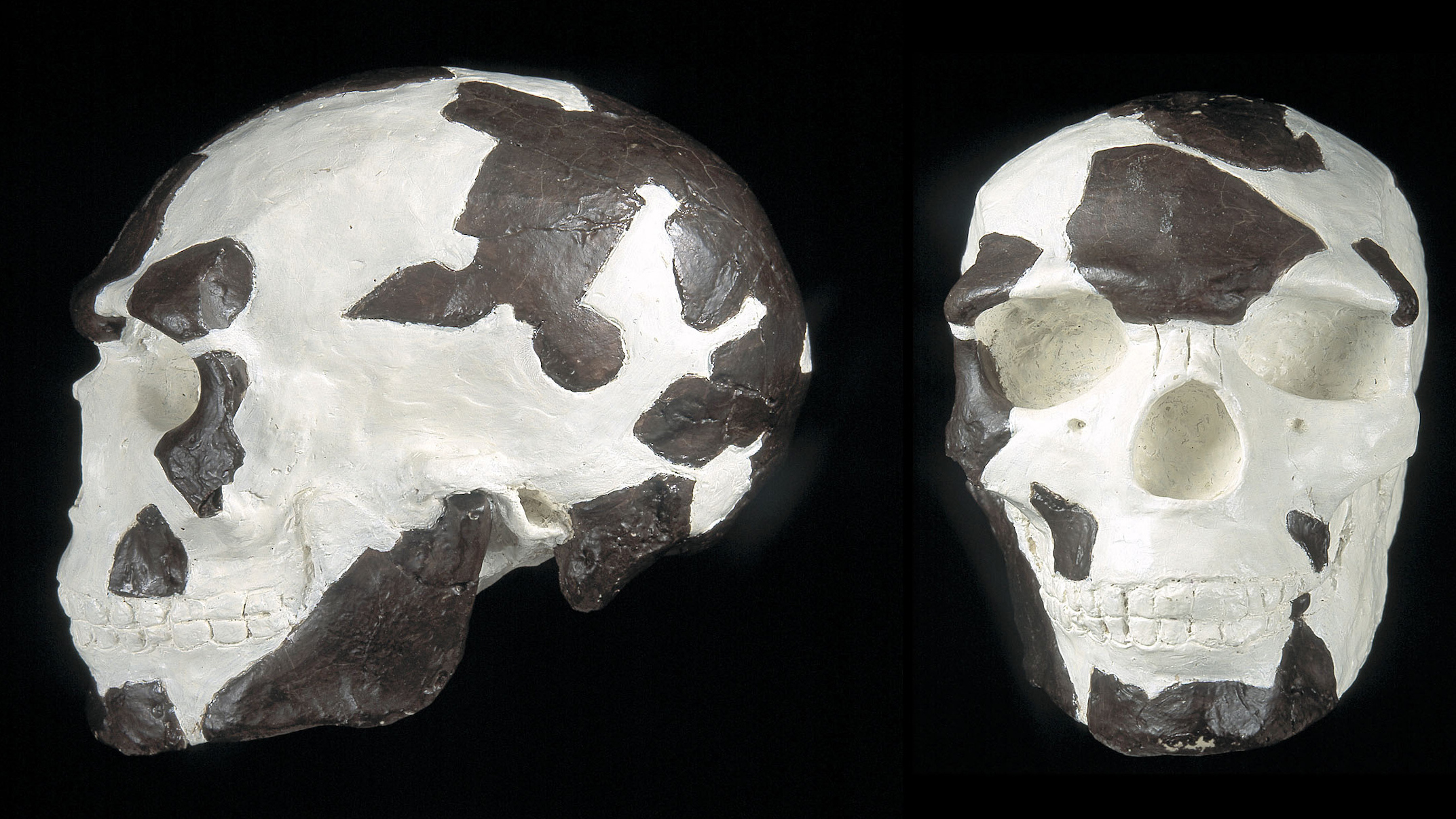

The new estimate places the fossils even more firmly among the oldest Homo sapiens remains ever discovered in Africa, second only to 300,000-year-old specimens found at the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco in 2017. However, the Jebel Irhoud skulls vary enough in their physical characteristics from those of modern humans for some scientists to contest their classification as Homo sapiens. This means that the new discovery marks the oldest uncontested dating of modern humans in Africa.

Related: See photos of our closest human ancestor

"Unlike other Middle Pleistocene fossils, which are thought to belong to the early stages of the Homo sapiens lineage, Omo I possesses unequivocal modern human characteristics, such as a tall and globular cranial vault and a chin," study co-author Aurélien Mounier, a paleoanthropologist at the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, said in a statement, referring to the globular cranial vault as the space where the brain sits inside the skull. "The new date estimate, de facto, makes it the oldest unchallenged Homo sapiens in Africa."

The remains were found in the East African Rift valley, an active continental rift zone where the African tectonic plate is in the process of splitting into two smaller plates, the Somali Plate and the Nubian Plate. Despite discovering the fossils more than 50 years ago, scientists have found it difficult to give the Omo I remains a conclusive age. The fossils lacked nearby stone artifacts or fauna that could be dated, and the ash they were buried under was too fine-grained for radiometry — a method that quantifies the amounts of certain radioactive isotopes (versions of an element with a different number of neutrons in the nucleus) with known decay rates.

To get around these issues, the researchers collected pumice samples from the Shala volcano more than 248 miles (400 kilometers) away, grinding them down until they were less than a millimeter in size. By performing a chemical analysis on the pumice found at the volcano and comparing it to the ash layer in the sediment above where the fossils were found, the researchers were able to confirm that both shared the same chemical make-up, and therefore came from the same eruption. It turned out the pumice samples, and the ash layer, are roughly 233,000 years old — meaning that the Omo I fossils found below the ash are at least the same age or older.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"First, I found there was a geochemical match, but we didn't have the age of the Shala eruption," lead author Céline Vidal, a volcanologist at Cambridge University, said in the statement. "I immediately sent the samples of Shala volcano to our colleagues in Glasgow so they could measure the age of the rocks. When I received the results and found out that the oldest Homo sapiens from the region was older than previously assumed, I was really excited."

It is probably no coincidence that some of humanity's earliest ancestors lived in a geologically active rift valley, Clive Oppenheimer, a volcanologist at Cambridge University, said in the statement. The tectonic activity created lakes that collected rainwater, not only providing fresh water but also attracting animals to hunt; and the 4,350-mile-across (7,000 km) Great Rift valley — of which the East African Rift valley is just a small part — served as an enormous migration corridor, for humans and animals that ran from Lebanon in the north all the way to Mozambique in the south.

Despite having found the minimum age of the Omo I samples, the researchers still need to find a maximum age for both these fossils and the wider emergence of Homo sapiens in eastern Africa. They plan to do this by linking more buried ash to more eruptions from volcanoes around the region, giving them a firmer geological timeline for the sedimentary layers around which fossils in the region are deposited.

"Our forensic approach provides a new minimum age for Homo sapiens in eastern Africa, but the challenge still remains to provide a cap, a maximum age, for their emergence, which is widely believed to have taken place in this region," co-author Christine Lane, a geochronologist at Cambridge University, said in the statement. "It's possible that new finds and new studies may extend the age of our species even further back in time."

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.