How to watch the 'ring of fire' solar eclipse on Thursday

Remember, never look directly at the sun.

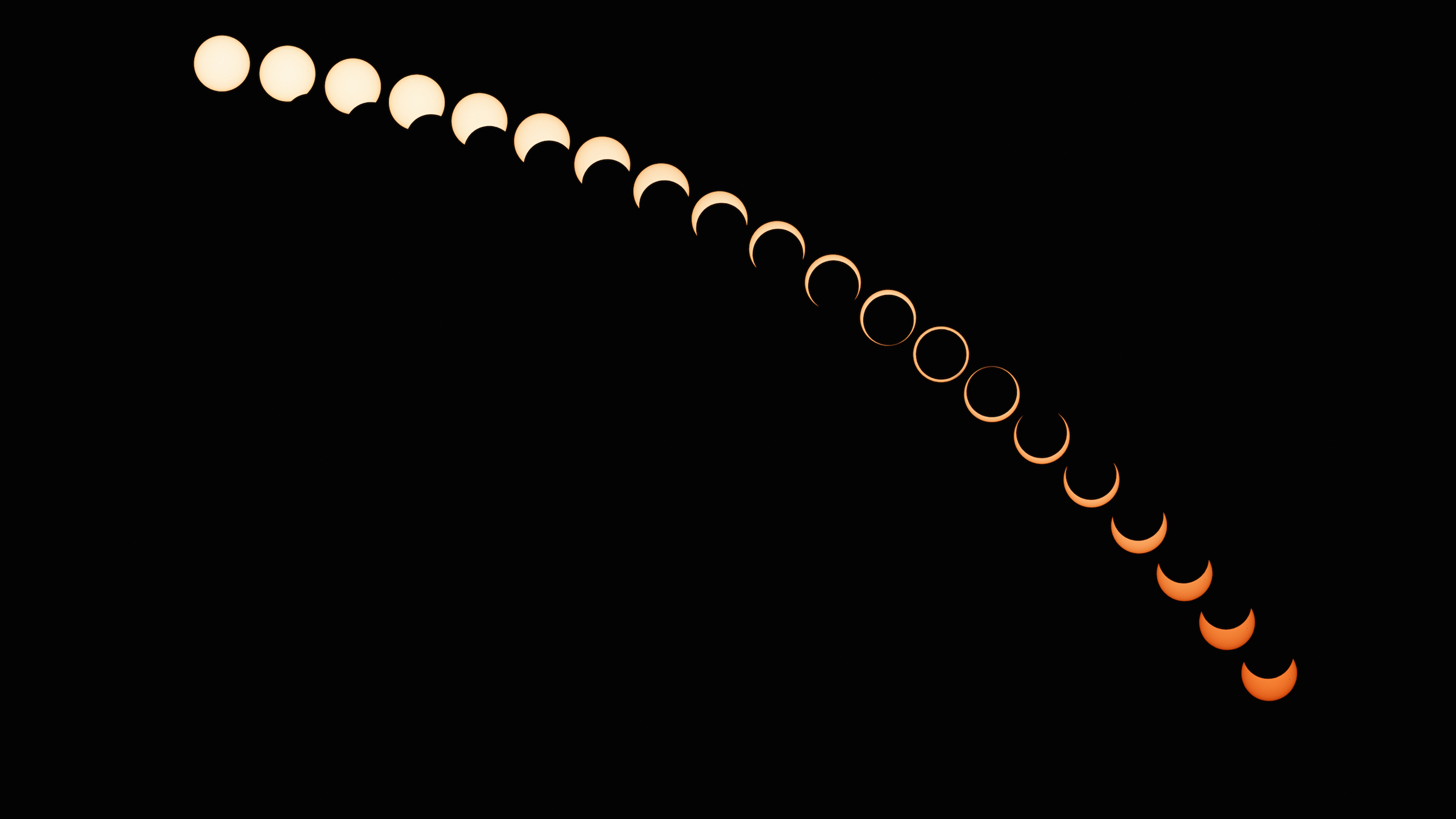

In the first solar eclipse of the year, the moon will almost entirely block the sun, leaving only a fiery ring of Earth's star visible Thursday (June 10) morning.

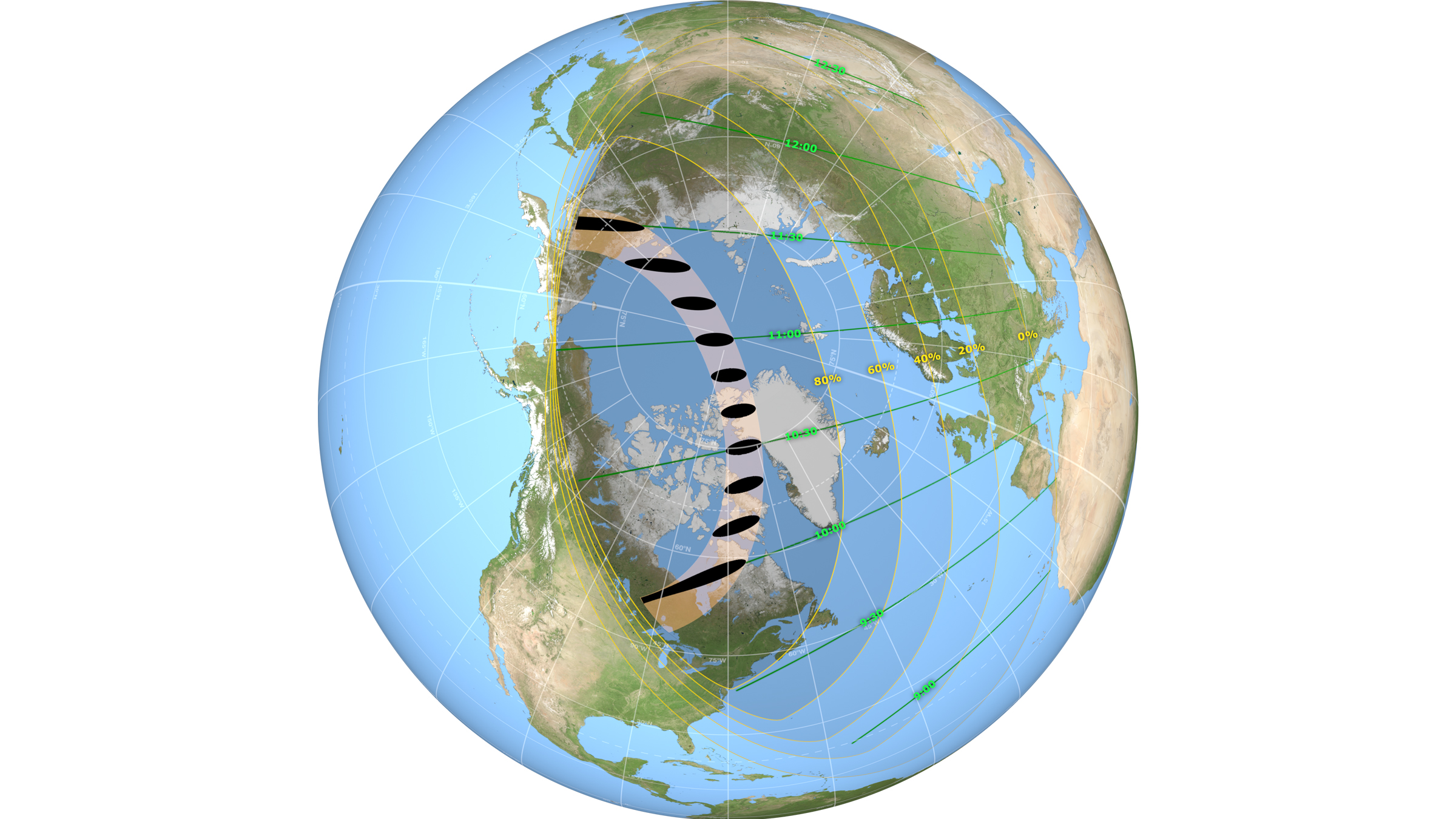

Skygazers in just a few places — in parts of Canada, Greenland and northern Russia — will be able to spot this fiery ring, also known as an annular eclipse, according to NASA.

However, a partial solar eclipse — when the moon takes a circular "bite" out of the sun — will be visible in more areas of the Northern Hemisphere, including parts of the eastern United States and northern Alaska, much of Canada, and parts of the Caribbean, Europe, Asia and northern Africa, NASA reported.

Related: Photos: 2017 Great American Solar Eclipse

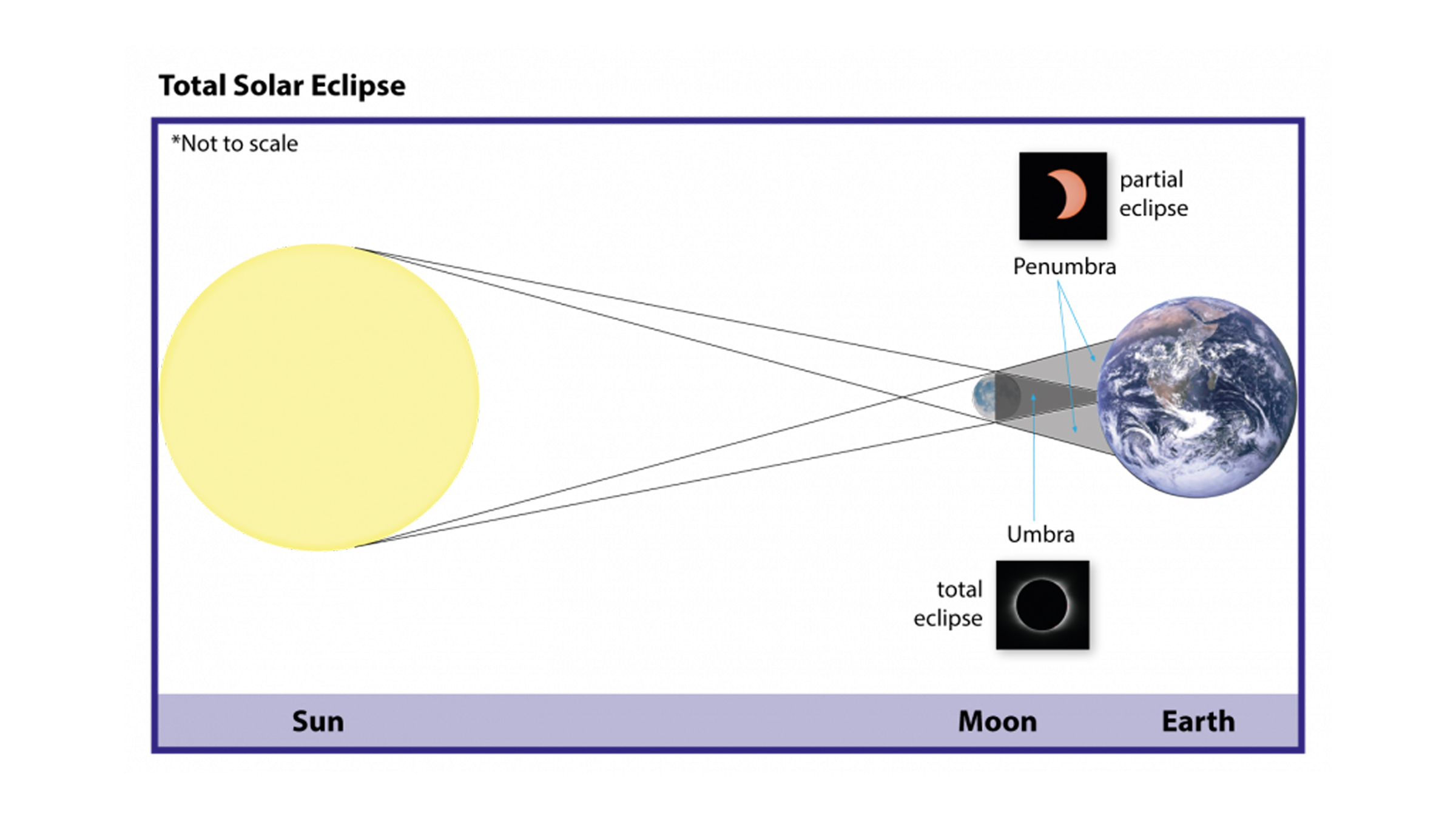

Solar eclipses happen when the moon scoots between Earth and the sun, blocking some or nearly all of the sun's light. During an annular eclipse, the moon is far enough away from Earth that it's too small to block out the entire sun. Instead, as the moon glides across the sun, the outer edges of the sun are still visible from Earth as an annulus, or ring.

The entire annular solar eclipse will last about 100 minutes, starting at sunrise in Ontario, Canada, and traveling northward until the moment of greatest eclipse, around 8:41 a.m. local time in Greenland (6:41 a.m. EDT; 11:41 GMT) 10:41 UTC in northern Greenland and ending at sunset in northeastern Siberia, according to EarthSky. The "ring of fire" phase, when the moon covers 89% of the sun, will last up to 3 minutes and 51 seconds at every point along this path.

Some regions that don't fall along the solar eclipse's path will see a partial eclipse, weather permitting. In these areas, part of the moon's outer, lighter shadow, known as the penumbra, blocks the sun. As the moon passes in front of the sun, it will look like this shadow took a sumptuous bite out of the bright star. For viewers in the United States, it's best to watch before, during and shortly after sunrise, depending on your location, especially if you're in parts of the Southeast, Northeast or Midwest, or in northern Alaska, NASA reported. In other words, make sure you have a clear view of the horizon as the sun tries to greet the new day but is partially blocked by the moon.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In New York, for instance, the maximum eclipse will happen at 5:32 a.m. EDT, according to Space.com, a Live Science sister site.

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, skywatchers will see up to 38% of the sun blocked out during the partial eclipse shortly after 11 a.m. local time, according to the Royal Astronomical Society.

The below NASA video shows the solar eclipse's path across Earth:

In contrast, the widely watched Great American Solar Eclipse in 2017 was a total solar eclipse, meaning the moon completely blocked out the sun. Viewers in U.S. states on a path from Oregon to South Carolina got to witness the eclipse's totality, when the moon completely blocked the sun, allowing people to gaze upward without eye protection. (This is safe, however, only during the brief moment when the moon entirely blocks the sun.)

Because this week's eclipse won't include totality, you should not look directly at the eclipse, even if you are wearing sunglasses. Instead, you'll need special eclipse glasses or other tools, such as a homemade solar eclipse viewer (here's a step-by-step guide) or even a spaghetti strainer or colander, which will show the partial eclipse's shadow if you let the sun shine through its holes and onto the ground or another surface.

If the weather or your location prevents you from seeing the eclipse, you can watch it live starting at 5:30 a.m. EDT (9:30 UTC) at the Virtual Telescope Project.

If you miss this solar eclipse, you still have one more shot this year. The second and final solar eclipse of 2021 will take place on Dec. 4. Although a total solar eclipse will be visible only from Antarctica, people in southern Africa, including Namibia and South Africa, can catch a glimpse at a partial solar eclipse, according to timeanddate.com.

Editor's note: Remember to NEVER look directly at the sun during most of an eclipse, or at any other time, without proper protection. Only during the very brief period of totality are you safe to gaze at the sun with the naked eye, because the moon's shadow has completely blotted out the light. But at all other times, looking directly at the sun can harm your eyes. You must wear solar eclipse viewers; sunglasses won't do the trick. Here's a visual step-by-step guide (and a video) for how to make your own viewers.

If you're wearing proper eye protection, Live Science would like to publish your solar eclipse photos, including those with your solar eclipse viewers or colanders! Please email us the image at community@livescience.com. Please include your name, location and a few details about your viewing experience that we can share in the caption.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.