Super Flower Blood Moon eclipse: How to watch early Wednesday morning

It's the first total lunar eclipse in nearly 2.5 years.

Everyone in the U.S. has a front-row seat to the supermoon lunar eclipse showcasing early Wednesday morning (May 26). So, weather permitting, here's how anyone along the eclipse's path can catch the bright full moon dim into a rusty red during its three phases: penumbral, partial and total lunar eclipse.

First off, no matter your location, it's important to be chill. At about five hours, the entire eclipse is longer than a feature-length film. But unlike an action flick that jumps straight into a fight scene, May's full moon will darken slowly. So grab a blanket and popcorn and find a comfortable spot where your eyes can adjust to the dark night sky.

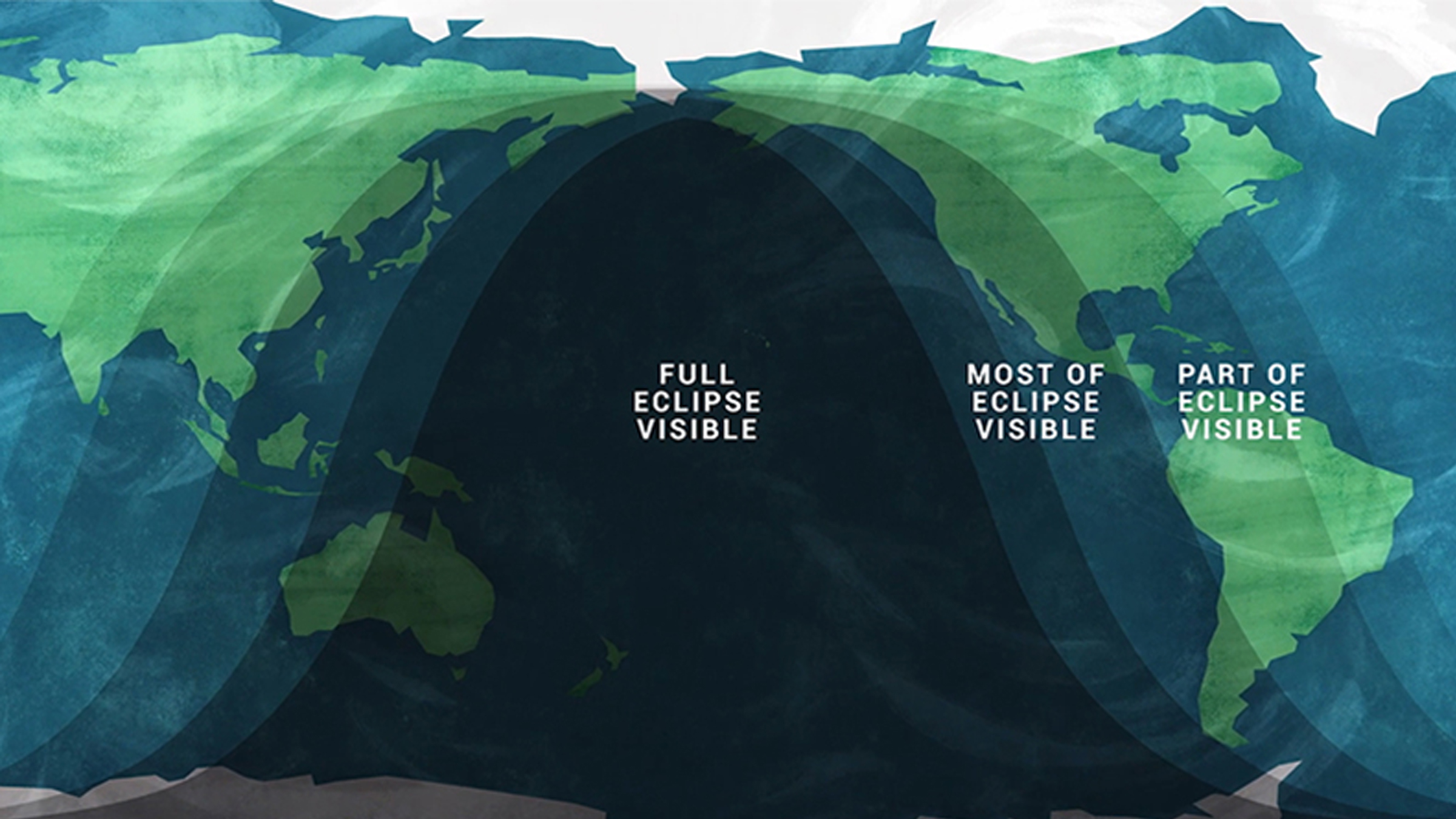

Just like a summer blockbuster, this lunar eclipse is a long time coming. It's been nearly 2.5 years since the last total lunar eclipse, according to NASA. During a lunar eclipse, the sun, Earth and moon (in that order) must perfectly align, so that Earth's shadow eclipses, or falls on, the moon. The best places to see the entire eclipse are Australia, parts of the western United States (especially Hawaii and Alaska), western South America and Southeast Asia, according to timeanddate.com.

Related: Glitzy photos of a supermoon

Like any other full moon, skywatchers will be able to watch May's Flower Moon — named for the wildflowers blooming in the Northern Hemisphere — rise in the sky around dusk. After moonrise, the feature show — the lunar eclipse — starts several hours later at 4:47 a.m. EDT on May 26 (08:47 UTC). During this initial phase, called the penumbral eclipse, the moon will move into Earth's light shadow, known as the penumbra.

Darkening from Earth's light shadow during penumbral eclipses is typically hard to see with the naked eye, NASA reported. "From within this zone, Earth blocks part but not the entire disk of the sun," according to NASA. "Thus, some fraction of the sun's direct rays continues to reach the most deeply eclipsed parts of the moon during a penumbral eclipse."

Next, at 5:44 a.m. EDT (09:44 UTC), Earth's dark shadow — known as the umbra — will begin to cover the moon. This marks the beginning of the partial lunar eclipse. Unlike the penumbral portion, the partial eclipse is visible to the naked eye. "The lunar limb extending into the umbral shadow usually appears very dark or black," NASA reported. "This is primarily due to a contrast effect because the remaining portion of the moon in the penumbra may be brighter by a factor of about 500x. Because the umbral shadow's diameter is typically about 2.7x the moon's diameter, it appears as though a semi-circular bite has been taken out of the moon."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) also noticed that Earth's umbral shadow on the moon was curved during partial eclipses, and this helped him decipher that Earth was round, according to NASA. Aristotle realized that no matter where people saw the eclipse or whether the moon was high or low in the sky when they saw it, the dark umbral shadow was always curved. Only a sphere could cast a round shadow from all angles, he reasoned.

Finally, the total lunar eclipse will begin at 7:11 a.m. EDT (11:11 UTC). For roughly the next 14 minutes, the moon will be completely covered by Earth's dark umbral shadow, reaching the maximum eclipse at 7:18 EDT (11:18 UTC). During this time, called totality, the moon will look like it's rusty red. This happens because the sun's light bends around the edges of Earth. This light travels through Earth's atmosphere, which filters out the shorter blue wavelengths but lets the longer reddish wavelengths through.

It's these reddish wavelengths that hit the moon, giving it an ochre color until totality ends at 7:18 EDT (11:18 UTC).

| Eclipse stage | Time: EDT | Time: UTC |

|---|---|---|

| Penumbral eclipse | 4:47 a.m. – 9:49 a.m. | 08:47 – 13:49 |

| Partial eclipse | 5:44 a.m. – 8:52 a.m. | 09:44 – 12:52 |

| Full eclipse | 7:11 a.m. – 7:25 a.m. | 11:11 – 11:25 |

| Maximum eclipse | 7:18 a.m. | 11:18 |

You might be out of popcorn by now, but it's worth it to stay for the rest of the eclipse. After totality, the moon will be in a partial eclipse until 8:52 a.m. EDT (12:52 UTC). After that, the end of the penumbral eclipse at 9:49 a.m. EDT (13:49 UTC) marks the end of the show.

Not all places will be able to see the eclipse in its entirety. Check the map below to see which phases will be visible to you. For instance, New Yorkers will only get to see the first penumbral eclipse because the sun rises at 5:31 a.m. EDT on Wednesday, according to sunrise-and-sunset.com.

The Flower Moon has another treat, no matter how much of the eclipse you get to see. This is the closest a full moon will be to Earth this year, making it a supermoon. The moon follows an elliptical orbit around Earth, and it's typically an average of 240,000 miles (384,500 kilometers) away. But, at the instant of the full moon — 7:14 a.m. EDT (11:14 UTC) on May 26 — the moon will be 222,022 miles (357,311 km) from Earth, Heavens Above reported.

The eclipse gives stargazers another reason to look upward. Usually, supermoons are so bright, they drown out starlight, making it hard for stargazers to see the constellations. But during a lunar eclipse, the moon dims, so the stars will appear extra bright.

If cloudy weather gets in your way, tune into virtual lunar eclipse watching parties at Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles (streaming begins at 4:45 a.m. EDT; 08:45 UTC); Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona (streaming begins at 5:30 a.m. EDT; 09:30 UTC); the European Space Agency, which will be observing the eclipse from two locations in Australia (starting at 5:30 a.m. EDT; 09:30 UTC); and the Virtual Telescope Project in Rome (showing live views from Australia, New Zealand and the Americas starting at 6 a.m. EDT; 10:00 UTC, and another live stream at 3 p.m. EDT; 19:00 UTC showing the supermoon over Rome), according to Space.com, a Live Science sister site.

Editor's Note: Live Science would like to publish your Super Flower Blood Moon photos! If you snap an impressive shot of May's full moon and/or lunar eclipse, email us the image at community@livescience.com. Please include your name, location and a few details about your viewing experience that we can share in the caption.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.