Giant reservoir of 'hidden water' discovered on Mars

The water likely exists as ice, making the region ripe for future exploration.

An enormous cache of water has been found just a few feet beneath the surface of Mars.

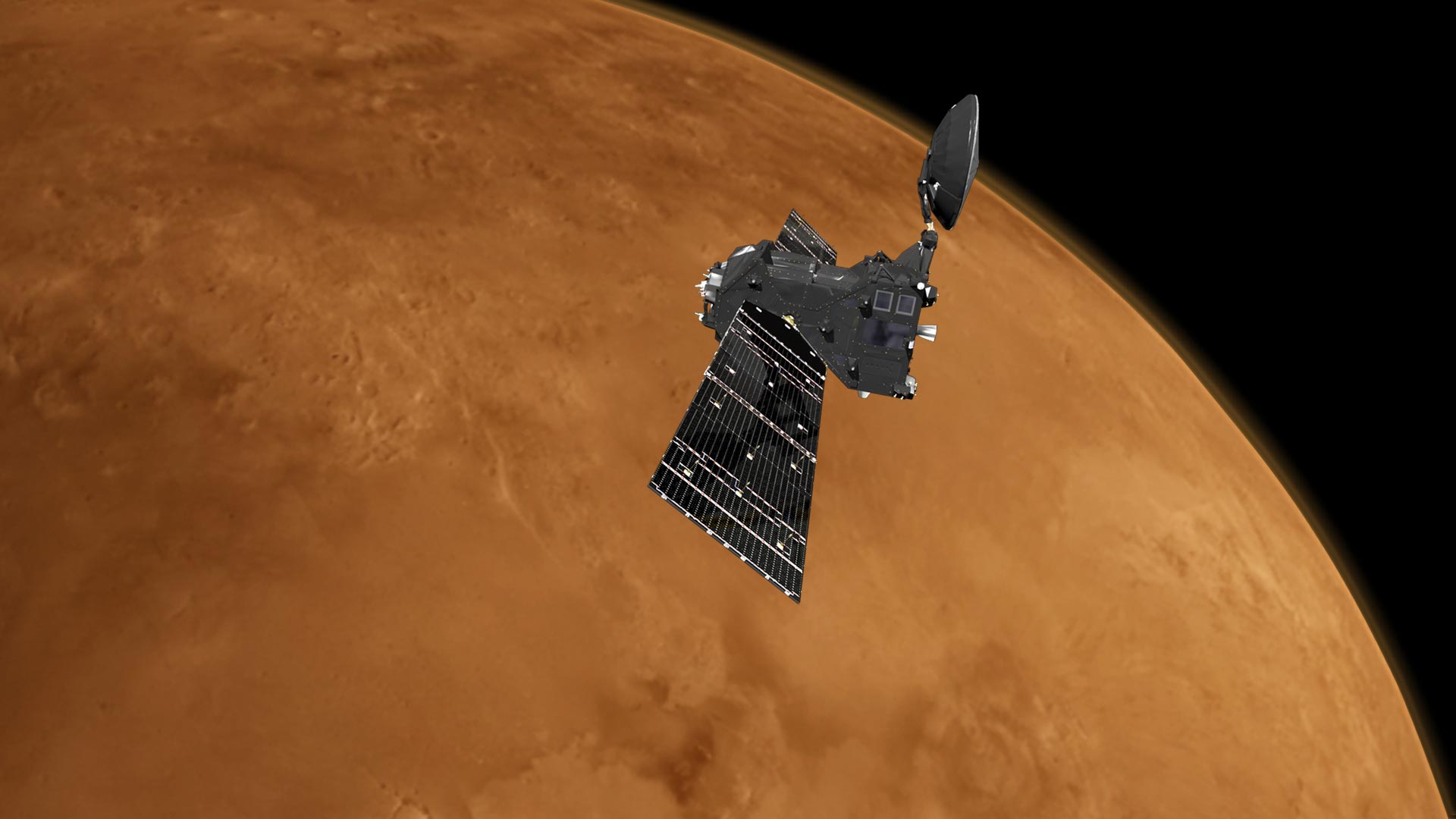

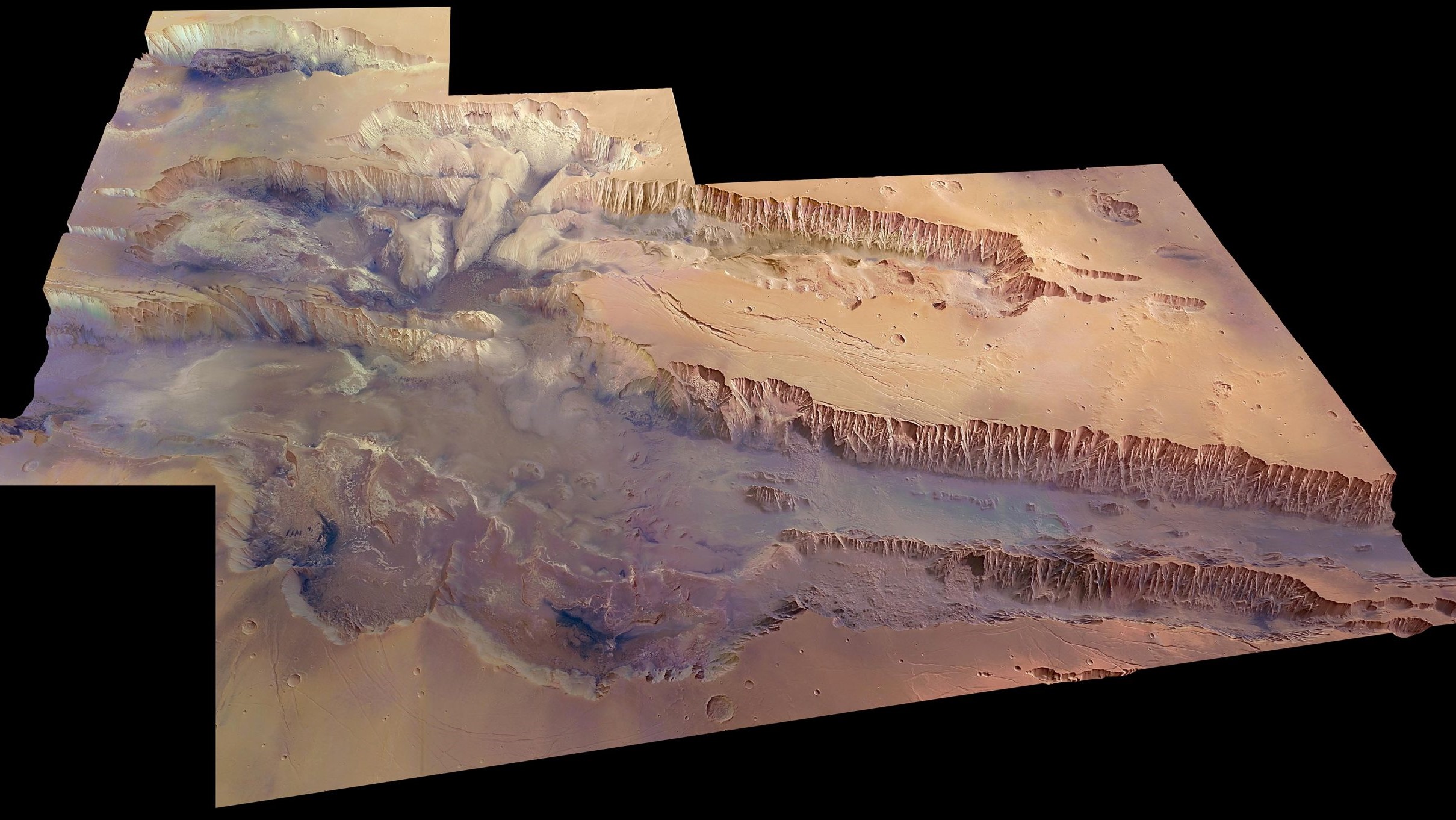

The European Space Agency's ExoMars orbiter has discovered "significant amounts of water" in the Valles Marineris canyon, the largest known canyon in the solar system. According to the researchers, 40 percent of the near-surface material of the 15,830 square mile (41,000 square kilometer) region could be water ice.

Data beamed back from the Trace Gas Orbiter's (TGO) Fine-Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector (FREND) instrument found unusually high levels of hydrogen, which alongside oxygen makes up water, at a site called Candor Chaos — a Netherlands-size region located at the heart of Valles Marineris. Since life on Earth is highly dependent on water, evidence of water on Mars could be a vital clue that the planet was once home to life — or that life could still be there.

The research, completed as part of a shared operation between the ESA and the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, is set to be published in the March 2022 edition of the journal Icarus, and was published online on Nov. 19.

Related: 6 reasons astrobiologists are holding out hope for life on Mars

"We found a central part of Valles Marineris to be packed full of water — far more water than we expected," co-author Alexey Malakhov, a scientist at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in a statement. "This is very much like Earth's permafrost regions, where water ice permanently persists under dry soil because of the constant low temperatures."

If the hydrogen detected is indeed bound together with oxygen to form water molecules, "as much as 40 percent of the near-surface material in this region appears to be water," study lead author Igor Mitrofanov said in the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Valles Marineris canyon is a gigantic tectonic crack in the Martian surface smoothed out and broadened by erosion from wind and possibly water. The canyon is more than 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) long and 5 miles (8 km) deep, making it 10 times longer and five times deeper than Arizona's Grand Canyon. According to NASA, if the Valles Marineris were on Earth, the gigantic canyon would stretch across the continental United States — from New York all the way to California.

The TGO's FREND instrument enables the orbiter, which has been circling the Red Planet since 2018, to scan for clues of water by detecting neutrons emitted at or just below the Martian surface. As neutrons form when energetic particles called cosmic rays strike the Martian soil, drier surfaces emit more neutrons than wetter ones — enabling the team to calculate the amount of water on a surface by looking at the number of neutrons it produces. This method allows the TGO to detect water as far as 3.28 feet (1 meter) below the Martian surface.

In the past, when scientists have searched for water ice in Mars' equatorial region, they have only been able to find odd traces of the substance clinging to the dust on its surface. Now that the TGO can penetrate to the upper subsurface, our ability to find pockets of water on the Red Planet has expanded dramatically.

"With TGO, we can look down to one metre below this dusty layer and see what's really going on below Mars' surface — and, crucially, locate water-rich 'oases' that couldn't be detected with previous instruments," Mitrofanov said.

More observations will be needed before researchers can identify what type of water they have discovered — whether its ice or has become chemically bonded to minerals in the soil. But given that so much of the near-surface material in the region appears to be water, "overall, we think this water more likely exists in the form of ice," Malakhov said.

Whatever form the water may take, the discovery has identified a large, easily-explorable reservoir of water that future rovers could land near and investigate — both for water and for signs of life.

"Knowing more about how and where water exists on present-day Mars is essential to understand what happened to Mars' once-abundant water and helps our search for habitable environments, possible signs of past life, and organic materials from Mars' earliest days," Colin Wilson, ESA's ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter project scientist, said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.