Scientists transform water into shiny, golden metal

In a mind-bending experiment, scientists transformed purified water into metal for a few fleeting seconds, thus allowing the liquid to conduct electricity.

Unfiltered water can already conduct electricity — meaning negatively charged electrons can easily flow between its molecules — because unfiltered water contains salts, according to a statement about the new study. However, purified water contains only water molecules, whose outermost electrons remain bound to their designated atoms, and thus, they can't flow freely through the water.

Theoretically, if one applied enough pressure to pure water, the water molecules would squish together and their valence shells, the outermost ring of electrons surrounding each atom, would overlap. This would allow the electrons to flow freely between each molecule and would technically turn the water into a metal.

Related: The surprisingly strange physics of water

The problem is that, to squash water into this metallic state, one would need 15 million atmospheres of pressure (about 220 million psi), study author Pavel Jungwirth, a physical chemist at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague, told Nature News & Comment. For this reason, geophysicists suspect that such water-turned-metal might exist in the cores of huge planets like Jupiter, Neptune and Uranus, according to Nature News.

But Jungwirth and his colleagues wondered whether they could turn water into metal through different means, without creating the ridiculous pressures found in Jupiter's core. They decided to use alkali metals, which include elements like sodium and potassium and hold only one electron in their valence shells. Alkali metals tend to "donate" this electron to other atoms when forming chemical bonds, because the "loss" of that lone electron makes the alkali metal more stable.

Alkali metals can explode when exposed to water, and Jungwirth and his colleagues have actually studied these dramatic reactions in the past, according to Cosmos Magazine. But they theorized that, if they could somehow avoid the explosion, they could borrow electrons from alkali metals and use those electrons to turn water metallic.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

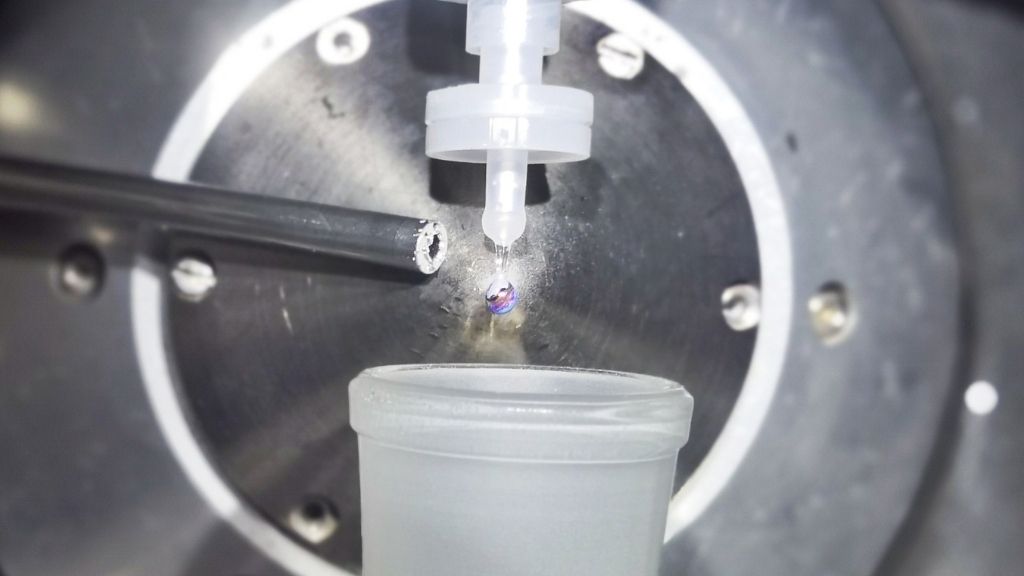

In their new experiment, described in a report published Wednesday (July 28) in the journal Nature, the team did just that. In the experiment, they placed a syringe filled with sodium and potassium in a vacuum chamber, squeezed out small droplets of the metals, which are liquid at room-temperature, and then exposed said metal droplets to a tiny amount of water vapor. The water formed a 0.000003 inch (0.1 micrometer) film over the surface of the metal droplets, and immediately, electrons from the metals began rushing into the water.

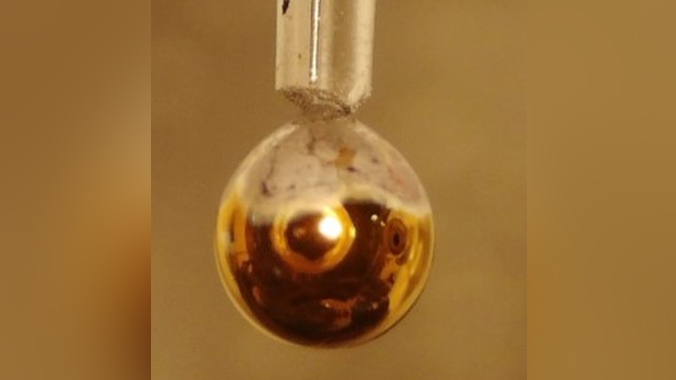

For the experiment to work, the electrons had to move faster than an explosive reaction could take place, Jungwirth told Nature News. And once the electrons zoomed from the alkali metals to the water, an incredible thing happened: For a few short moments, the water turned a shiny, golden yellow color. Using spectroscopy, the team was able to show that the bright yellow water was in fact metallic.

"Our study not only shows that metallic water can indeed be produced on Earth, but also characterizes the spectroscopic properties associated with its beautiful golden metallic luster," study author Robert Seidel, head of the Young Investigator Group at Humboldt University of Berlin, said in the statement. "You can see the phase transition to metallic water with the naked eye," he added.

"It was amazing, like [when] you discover a new element," Jungwirth told Nature News & Comment.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.