In a historic launch, the Webb Telescope blasts off into space

"From a tropical rainforest to the edge of time itself."

Heads up, Hubble — another massive space telescope just launched on a historic mission to observe the faintest, oldest objects in the universe in unprecedented detail.

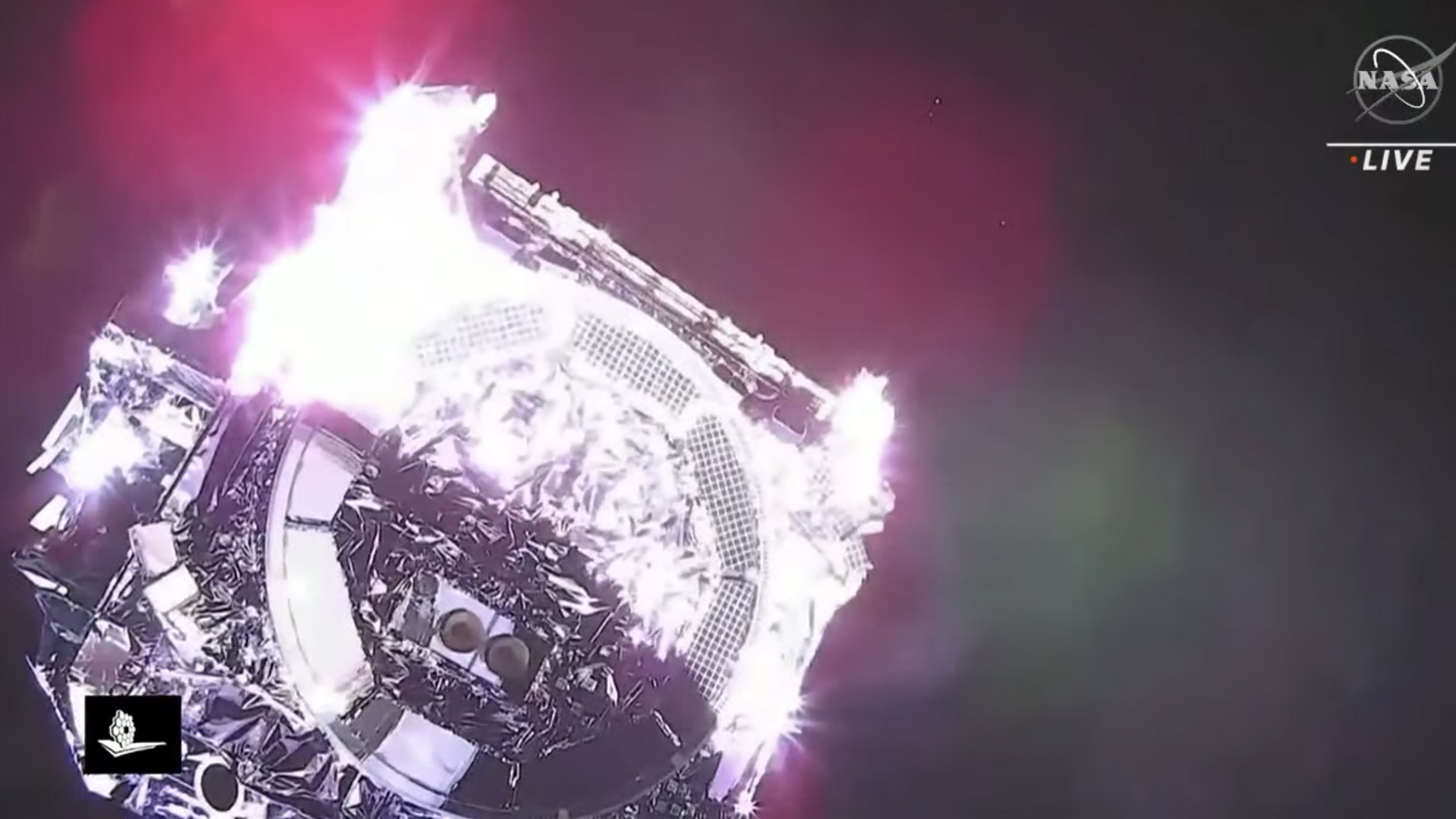

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), a school-bus-size satellite observatory weighing about 14,000 pounds (6,350 kilograms), lifted off the launch pad on Saturday (Dec. 25) at 7:20 a.m. ET (12:20 p.m. GMT). Carrying the telescope was a Ariane 5 rocket traveling at 25,000 mph (40,000 km/h) to escape Earth's gravitational pull. The telescope was folded up to fit neatly inside the nose of the rocket; once in space, it will unfold and deploy its mirrors and other instruments and assume its fixed orbital position, with observations scheduled to start six months after launch, NASA representatives said in a statement.

The Ariane 5 rocket and its precious cargo blasted off from the Guiana Space Centre, also known as Europe's Spaceport, in French Guiana. The mission is an international collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The JWST project has been in development for over two decades, according to the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), which is operating the new telescope.

Related: Building the James Webb Space Telescope (photos)

As the rocket ignited and lifted off from the launch pad, JWST began its journey "from a tropical rainforest to the edge of time itself," according to NASA's live broadcast.

At 7:29 a.m. ET, the main stage rocket engine jettisoned, and the upper stage engine ignited for the 16-minute burn that would put the telescope in its preliminary orbit. That lasted until 7:45 a.m. ET, when JWST entered a 2-minute coasting phase. At 7:47 a.m., springs gently pushed the telescope away from the rocket, which performed a collision avoidance maneuver to direct it away from JWST.

As mission control team members shouted "Go Webb, go!", the telescope separated from the rocket and took its first solo steps in space. JWST's solar array deployed at 7:50 a.m. ET, and with the confirmation that "James Webb not only has legs, but it has power," cheers erupted across the mission control room.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We launch for humanity this morning," Stéphane Israël, CEO of Arianespace, said on NASA's YouTube broadcast. "After Webb we will never see the skies in quite the same way."

Building the telescope cost nearly $10 billion — almost doubling the estimated cost since 2009, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office — and that very expensive observatory is now headed for a destination that's nearly 1 million miles (1,600,000 kilometers) from Earth. It won't be possible for astronauts to visit JWST to perform repairs if anything goes wrong, as they did for the Hubble Space Telescope, so team members and agency officials had been closely monitoring equipment and weather to make sure that launch conditions were optimal and that everything onboard was operating as it should prior to launch.

Originally scheduled to take off in 2018, JWST was then expected to launch in 2020 and then 2021, due to challenges including concerns about instruments and restrictions posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to NASA. In 2021, an Oct. 31 launch was postponed to November and then to December; the latest postponement, from Dec. 24, followed reports of inclement weather at the launch site in South America, NASA representatives said in a statement.

With JWST finally aloft, teams of scientists and engineers will eagerly await signals indicating that the next stages of JWST's deployment are underway, as the telescope unfurls all of its gear and prepares to become fully operational.

About a day after launch, JWST will extend its antenna toward Earth. After three days, sunshield deployment begins, taking place in stages over the next week. Mirror segments that were previously folded back will then be moved into position alongside the primary mirrors, and by 13 days after launch the telescope will be fully deployed; however, its components will still undergo months of testing in space before observations and data collection begin, according to NASA.

"Follow the dust"

Six months from now, when JWST is up and running, it's going to be very, very busy. Its sensitive imaging and spectroscopy instruments will enable researchers to penetrate dense clouds of cosmic dust and collect data from objects that are so faint they are almost undetectable by other telescopes, and JWST's infrared "eyes" are the most powerful ever sent into space, said astrophysicist Jackie Faherty, a senior scientist in the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Faherty is one of the first scientists in line to collect observations with JWST, and she plans to aim it at brown dwarfs (sometimes called "failed stars," according to NASA). Brown dwarfs are dim, cool objects that are more massive than gas giant planets like Jupiter, and less massive than the smallest stars. And they fall right in the sweet spot of JWST's wavelengths, Faherty told Live Science.

When looking at brown dwarfs in recent years, "we've been scraping the bottom of the barrel of photons from any instrument we can get our hands on," even powerhouse tools such as the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer, she said. But with the arrival of JWST, "we're not at the bottom of the barrel anymore. JWST is like turning the faucet on, and then all of a sudden it's pouring water at you; and that's when the secrets start flowing."

In other words, where researchers were previously "squinting and guessing" about the composition of brown dwarfs, "JWST is gonna be like, boom! Here you go, this is all the data that you've ever wanted," Faherty said. "It's so exciting to consider that."

Infrared instruments will also enable JWST to detect and look through cosmic dust clouds surrounding starburst galaxies, which are hotbeds of star formation. Other researchers will use JWST to investigate dust shrouds enveloping energetic baby stars, known as Herbig-Haro objects, and to create and test models of the explosion that created the spectacular Crab Nebula. Astrophysicists are also lining up to investigate the atmospheres of exoplanets in the Trappist-1 system about 39 light-years from Earth, and to peer backward in time to discover the earliest galaxies. Because star birth begins in cosmic dust clouds, using JWST to "follow the dust" will offer new insights into the birth of stars, planets and galaxies that make up our universe, Faherty said.

"It's like breadcrumbs back to the secrets of how the first galaxies formed, and how they ended up evolving and then turning into what we know in our local area to be the way the universe looks today, nearly 14 billion years after the Big Bang," she said.

What's in a name?

JWST promises a bright future of never-before-seen cosmic observations. But the telescope's name, which was picked in 2002, comes with baggage from a darker period in NASA's past.

James Webb was the space agency's second administrator, serving from Feb. 14, 1961 to Oct. 7, 1968, and under his watch, NASA launched the lunar exploration missions of the pioneering Project Apollo, according to a NASA biography. However, critics of Webb point out that Webb also oversaw the agency at a time when gay and lesbian employees experienced discrimination and persecution, Live Science's sister site Space.com previously reported. Prior to Webb's tenure at NASA, he served as the U.S. Undersecretary of State from 1949 to 1952, "during the purge of queer people from government service known as the 'Lavender Scare,'" according to an online petition for renaming the JWST.

"Archival evidence clearly indicates that Webb was in high-level conversations regarding the creation of this policy and resulting actions," the petition stated. It launched in May and has since garnered more than 1,700 signatures.

Some astronomers have argued that putting Webb's name on this important telescope legitimizes discrimination. NASA agreed to investigate the matter, but in late September the agency announced that the mission would proceed with the telescope bearing the Webb name as planned, Nature reported on Oct. 1.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.