What's the weirdest sea creature ever discovered?

We're spoiled for choice.

What is the strangest animal ever discovered in the sea? Woo boy. We've got options.

Even sea creatures that people tend to be familiar with are pretty weird. Take flounder, with their flat bodies and doubled-up eyes, or oysters, which appear to be, let's face it, mostly mucus? And what about whales? We're all just okay with the concept of baleen?

But it only gets stranger. In coral reefs and at deep-sea vents; at midocean ridges and in the dark, cold depths, animals have evolved some truly bizarre bodies and habits in order to survive. The result are creatures as alien as anything that might one day be found on a far-flung planet. Sea creatures survive without light, in almost no oxygen, at incredible pressures — wherever they can eke out an existence.

So who's the weirdest? We asked several marine biologists to find out.

Related: 10 weird creatures found in the deep sea in 2021

Coral reef creatures

Coral reefs are home to thousands of species, so it's no surprise that some are very strange. Coral itself is pretty weird; after all, reefs are built by coral polyps, relatives of jellyfish that extract calcium carbonate from the water to construct protective homes shaped like brains, fans and plants. Even weirder, most coral polyps wouldn't survive without a symbiotic relationship with an alga called zooxanthella, which lives inside polyps and provides energy via photosynthesis in return for shelter and carbon dioxide.

The animal-built habitat of a reef, in turn, shelters other strange creatures. Take the rose-veiled fairy wrasse (Cirrhilabrus finifenmaa), which lives in deep, poorly lit reefs called "twilight reefs." These fish look like something a 6-year-old with access to the 64-crayon Crayola box might dream up: Their bodies are a rainbow of pink, orange, purple and blue. Research published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B in 2020 found that coral reefs provide the perfect environment for the evolution of gaudy colors. The clear water allows males and females to see each other well, and they may evolve colorful bodies to attract mates; the structural refuge offered by hard corals means that animals face less costs for their showiness than animals in more open waters, because they can more easily escape predators despite being quite visible.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another common coral reef denizen is the bullethead parrotfish (Chlorurus sordidus), which has some of the strongest teeth on Earth, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History — all the better to chew up the hard exoskeletons of coral to get to the tasty polyps inside. As if this diet weren't odd enough, parrotfish also sleep in cocoons of their own mucus to protect themselves from blood-sucking parasites.

Perhaps the weirdest animals found in reefs and off the coasts of tropical Pacific islands, however, are the sacoglossans. Sacoglossan translates to "sap-sucking," said Jeanette Davis, a marine microbiologist, science communicator and author of the children's book "Jada's Journey Under the Sea" (Mynd Matters Publishing, 2022). Sacoglossans are more often known as "solar-powered sea slugs," Davis told Live Science. These colorful slugs feed on algae, stealing some of the algal chloroplasts, cellular organs that enable photosynthesis. Yep, these slugs can glean energy right from the sun. They can also use molecules from the algae for defense, and some of them could help defend human health, too.

"Through my work as a marine microbiologist, I worked with a team of scientists to ultimately help discover an anti-cancer compound that is produced by a marine bacterium associated with alga that is hijacked by a sacoglossan and used as a defense molecule," Davis said.

Floating in the deep

The open waters of the ocean aren't as chock-full of life as coral reefs. But what does live there is almost universally weird, especially in the darker, deeper reaches. Making a strong case for absolute weirdest are siphonophores.

"People struggle to understand siphonophores at all," said Steven Haddock, a marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute who studies these oddities as well as other gelatinous creatures. Siphonophores operate like a single organism, but they're actually colonies of individual, asexually reproducing organisms that take on different roles within the larger whole. Researchers in Australia once observed siphonophores up to 150 feet (45 meters) long. Haddock told Live Science that his personal favorite siphonophore is Erenna sirena, which uses red bioluminescent lures to attract prey.

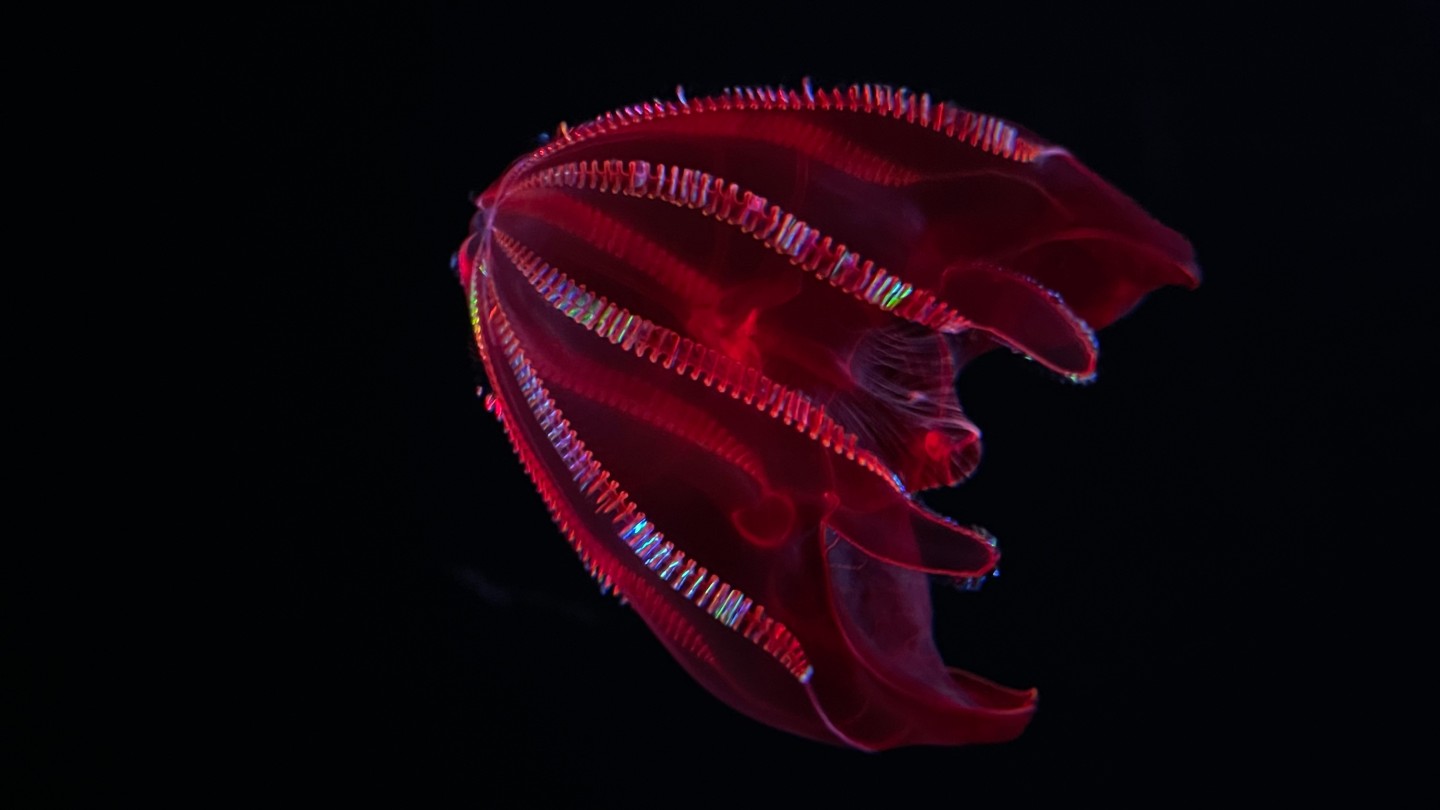

Another gelatinous favorite for Haddock is the bloody-belly comb jelly (Lampocteis), a deep-sea ctenophore. Ctenophores don't sting like jellyfish do; rather, they sport sticky cells to entrap prey. The eerily named bloody-belly comb jelly is bold red and propels itself through the depths with tiny beating cellular projections called cilia, which seem to sparkle as light hits them.

Also resplendent in red is the strawberry squid (Histioteuthis heteropsis), a resident of the ocean's twilight zone. It has one large (and strikingly green) eye that looks upward to spot shadows cast by prey and one small eye that looks downward, seeking out signs of bioluminescence from prey swimming below. For weirdness, though, the strawberry squid doesn't hold a candle to the bigfin squid (Magnapinna), which has a body as long as a dollar bill and tentacles as long as a human. These distinctive squid are known for their tentacles that bend at a 90-degree angle, creating a weird "elbow." They've been sighted only about 20 times since their discovery more than a century ago.

Life at the bottom

Animals that hope to survive at the bottom of the sea have to do without light and stand up to the incredible pressure of thousands of meters of water. Famous residents include the blobfish, which looks fairly unassuming while swimming thousands of feet below the surface but deflates into a saggy sack when brought to the surface, where the pressure is 100 times less than what the fish is adapted to.

Scientists are only beginning to catalog the other odd creatures at the ocean depths. Javier Sellanes López, a marine biologist at Catholic University of the North in Chile, has been exploring the seamounts off the coast of South America, turning up an array of new or poorly understood species. Take Eunice decolorhami, a polychaete worm found living in tubes 590 to 1,115 feet (180 to 340 m) deep on the slopes of the Desventuradas Islands and the seamounts of the Nazca Ridge. With what appears to be bulbous eyeballs and an underbite, these animals look more like background characters in "The Muppet Show" than marine worms.

The researchers have also turned up samples of the eerie white-and-red crab Ebalia sculpta, a bottom dweller that scuttles amid tube worms and anemones about 650 feet (200 m) below the surface.

"Its main distinguishing feature is a face carved into its cephalothorax [fused head and body] that resembles the image of an underworld being," Sellanes López told Live Science. In other words, it's a deviled crab.

But let's go deeper. Lisa Levin, a biological oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, nominated xenophyophores as one of her favorite strange deep-sea creatures. Xenophyophores are single-celled organisms called protozoans that clump together sediments to form elaborate houses called "tests." These tests look a bit like plants, corals or large lichens. They're found below about 1,300 feet (400 m) well into deep-ocean channels such as the Mariana Trench and, in this barren world, provide shelter for invertebrates and developing fish embryos, Levin told Live Science.

"I find the fact that a protozoan can make a home for invertebrates or provide nursery habitat for snailfish to be a delightful idea," Levin said.

Less delightful, perhaps, are bone-eating worms (Osedax), a deep-sea oddity suggested by Scripps Institution marine biologist Gregory Rouse. These feathery red worms eat without mouths or guts, instead excreting acid to break down bones of dead marine animals. Females grow to be about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long. Males are just one-twentieth of an inch (1 millimeter) long and live in jellylike tubes clinging to females, existing solely to fertilize the females' eggs.

So, what's the weirdest sea creature of all? It could be a crab carved with the face of Satan, a bioluminescent jelly thing that's actually a whole lot of little things, a slug that photosynthesizes or a worm that drills through bone with acid. Or maybe it's something else. If there's one guarantee in the ocean, it's that something weirder is always just around the corner.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.