20 of the weirdest sharks

Sharks are loveable weirdos — but a few may haunt your nightmares.

Does the word "shark" make you conjure up an image of an animatronic Jaws, rolling its dead eyes and gnashing its terrible teeth? While this image of great whites is iconic, there's so much more to sharks than that horror-movie portrayal. The shark world is full of big-eyed beauties, teeny-tiny cuties and a couple of species that might haunt your nightmares (you'll be glad to hear that the one with rotary-saw teeth went extinct long ago). Really, they're a bunch of lovable weirdos. Here are the strangest sharks to swim the seas.

20. Horn sharks

Horn sharks (Heterodontus francisci) are quiet, unassuming little sharks. They spend their days hiding in rock crevices in water less than 40 feet (12 meters) deep. At night, these sharks come out to hunt, but they're not sleek nightstalkers. Horn sharks are clumsy swimmers, and they sometimes even use their fins to crawl along the rock instead of swimming, according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium. This works out well for them, as they eat mostly molluscs and echinoderms like sea urchins.

As well as their ability to crawl, horn sharks are also set apart by their sharp spines, which project off both dorsal fins. These spines help protect the sharks from predators — they're prickly from the day baby horn sharks are born.

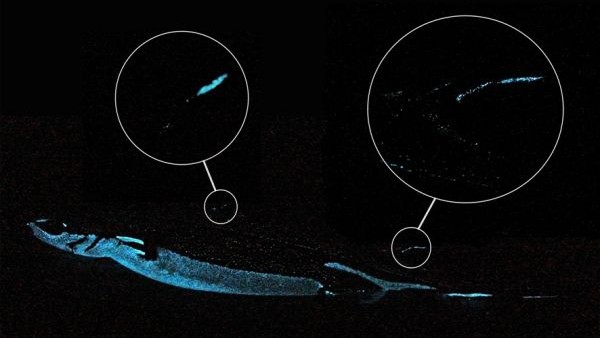

19. Pocket sharks

Not only do these sharks fit in the palm of a hand, they're shaped like tiny sperm whales. The cuteness is unbearable.

These are pocket sharks, or Mollisquama mississippiensis, a pint-sized new species discovered in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. The sharks aren't actually named for their size, but for a pocket-shaped orifice near their pectoral fin. Because only a few pocket sharks have ever been caught, researchers don't know much about their biology, but the pocket orifice may be used to excrete a pheromone or bioluminescent fluid, researchers told Fox News.

18. Whale sharks

At up to 33 feet (10 m) long, whale sharks are the biggest living species of fish in the world. But that's not what qualified them for a spot on this list. Instead, it's their eye-teeth.

In 2020, Japanese researchers discovered that whale shark eyes are surrounded by tiny teeth called dermal denticles. According to Phys.org, these dermal denticles line the bulging pockets that hold the sharks' eyeballs (they don't have eyelids). The denticles are shaped similar to human molars, and they may help protect the whale sharks' eyes from attacks by small ocean creatures.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

17. Godzilla sharks

Three hundred million years ago, Godzilla sharks made mincemeat of smaller fish in what was then an estuary and what is now New Mexico. Godzilla is just a nickname for these 6-feet-8-inches-long (2 m) monsters, though — their actual name is Hoffman's dragon sharks (Dracopristis hoffmanorum).

Pick your monster, Godzilla or dragon — either fits these sharks. The ancient animals had 12 rows of razor-sharp teeth and a reptilian-looking pair of 2-feet-5-inch-long (0.8 m) fins on their backs. These sharks may have lurked near the estuary bottom and hunted small vertebrates and crustaceans with their crushing jaws, their discoverers told Live Science.

16. "Pig-faced" sharks

Not only do these sharks have flattened, piglike snouts, they also grunt like pigs when pulled from the water. For that reason, people fishing in the Mediterranean often call them "pig fish."

The sharks are officially named angular roughsharks (Oxynotus centrina). These snub-nosed sharks grow to be about 3 feet 4 inches (1 m) long, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which lists angular roughsharks as a "vulnerable" species. The sharks are often accidentally caught in fishing nets, leading to declining population numbers.

15. Goblin sharks

These sharks are pretty spooky. Goblin sharks (Mitsukurina owstoni) have sharp, protruding teeth and long snouts, and their pinkish-purplish coloring looks weirdly mammalian. It's not hard to see how these sharks got their common name.

Unless you're a crustacean or cephalopod, though, goblin sharks are not likely to be a threat. According to The Australian Museum, goblin sharks are bottom-dwellers, staying near the ocean floor at depths of about 3,930 feet (1,200 m). Goblin sharks' creepy jaws extend outward to grab their prey. Their snouts are also studded with pores called ampullae of Lorenzini, which can detect tiny electrical charges coming off living organisms — a handy way to hunt in the deep, dark ocean.

14. Cookiecutter sharks

Cookiecutter sharks (Isistius brasiliensis) aren't very big — they grow to only about 20 inches (50 centimeters) long — but they are very, very bitey. Using their round, toothy jaws, these sharks sometimes nibble chunks off creatures much larger than themselves, including great white sharks, Live Science previously reported. At least one took a couple of bites out of a person in an attack that occurred between the islands of Hawaii and Maui in 2011. (The victim, a long-distance swimmer, recovered.) These sharks are named for their jaws, which look like cookiecutters and allow the sharks to scoop globs of flesh from their prey.

These sharks occupy an unusual place in the food chain. Most of their diet is made up of small, bottom-dwelling ocean animals that the sharks can swallow whole. But at night, cookiecutter sharks sometimes travel toward the ocean surface to munch on large prey like other sharks and orcas.

13. Frilled sharks

These frills can kill. Frilled sharks (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) get their name from their 300 three-pointed teeth, which are arranged in rows that look like frills. Growing up to 5 feet (1.5 m) long, frilled sharks punch above their weight when targeting prey, using their sharp, backward-facing teeth to nab fish, squid and other sharks twice their size.

Amazingly, these sharks have remained basically the same for 80 million years, since before the dinosaurs went extinct. They live between 65 feet and 4,900 feet (20 to 1,500 m) underwater in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

12. Skinless blackmouth catshark

A naked shark pulled from the Mediterranean in July 2019 wasn't a new species but a completely mystifying individual with a strange condition: It was apparently born without skin or teeth.

Inexplicably, this blackmouth catshark (Galeus melastomus) was doing fine when it was accidentally caught by fishermen. It was about 3 years old, was a typical size for its age (blackmouth catsharks grow to about 2 feet 4 inches, or 70 cm, long), and had a full belly.

"Our first reaction was, 'A shark without skin can't survive,'" Antonello Mulas, a biologist at the University of Cagliari in Sardinia, told Live Science at the time. "But, as Shakespeare said, there are more things in heaven and Earth than you can imagine."

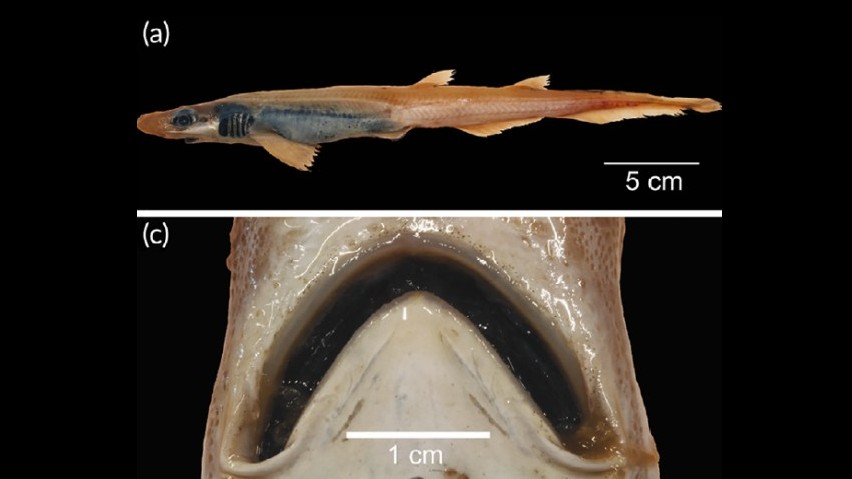

11. Viper dogfish

Viper dogfish (Trigonognathus kabeyai) might as well come from another planet. This species of deep-sea shark was only discovered in 1986, and it's been seen only rarely since. Distant relatives of goblin sharks, viper dogfish have a similar protruding jaw with a nasty set of scraggly teeth. But these creepy creatures are pip-squeaks: Viper sharks only grow to between 7 and 21 inches (18 to 53 centimeters) long.

Viper dogfish also glow. Bioluminescent organs called photophores line these sharks' undersides. Viper dogfish are part of the lanternshark (Etmopteridae) family, whose members all glow. This glow likely camouflages the sharks when seen from below, as the gentle glow melds with the sunlight filtering through the water. The light may also attract small prey in the dark ocean depths.

10. Ghost sharks

Gliding through the dark ocean about a mile (1,640 m) deep, pointy-nosed blue ratfish (Hydrolagus trolli) look like strange, silent phantoms. For that reason, these elusive sharks are sometimes known as "ghost sharks."

Ghost sharks were not formally identified until 2002, when researchers classified and named the species based on several dozen carcasses accidentally pulled in by fishing trawlers. Between 2000 and 2007, another group of scientists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in California captured a series of videos off the Central California coast showing living specimens.

Rounding out this species" weirdness is the spiky, club-like organ on the top of males' heads. This organ is used to position the female during copulation, according to Lonny Lundsten, a senior research technician at MBARI.

9. Cyclops dusky shark

In 2011, commercial fishermen pulled a dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus) from the waters of the Gulf of California. The shark was pregnant, but when the fishers examined her, they found that one of her fetuses was very unusual: It was an albino, and it also had only one eye — smack dab in the middle of its snout, like a cyclops.

Researchers who examined the shark fetus found that the eye was made of functional optical tissue, but the shark would likely have died outside the womb. Cyclopia is a developmental abnormality that occurs in a lot of species, including humans. It is usually associated with many other abnormalities and is typically fatal very soon after birth.

8. Genie's dogfish sharks

On the subject of eyes, Genie's dogfish sharks have some serious peepers. These sharks (Squalus clarkae) are deep-water creatures that live in the Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic. Their small size (20 to 28 inches long, or 50 to 70 cm) and giant baby-blues make them look like cuddly anime characters.

The shark species was discovered and formally described in 2018.

7. Swell sharks

Even sharks need to avoid predators. Swell sharks, which spend their days hiding in rocky crevices, have devised a clever plan to beat would-be predators: They slurp up a huge amount of seawater to swell to twice their normal size.

Swell sharks live all over the place, from the coast of California to the waters near the Philippines. Their swelling trick can intimidate predators if they're out at night on the hunt; and during the day, the sharks can swell up to lodge themselves inside their rocky hiding spots, preventing predators from pulling them out.

6. Velvet belly lanternsharks

Velvet belly lanternsharks (Etmopterus spinax), which are dogfish sharks found deep in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, have come up with another way to avoid being eaten: They stick a big, glowing sign on themselves saying, "Danger, spikes on shark are pointier than they may appear."

These sharks usually grow to no more than 2 feet (60 cm) long, so they're vulnerable to larger predators. Their light-up spines probably warn hungry hunters that they are a tough mouthful to swallow.

5. Phoebodus sharks

Phoebodus sharks were a strange bunch. They swam the seas about 350 million years ago and grew to 4 feet (1.2 m) long. The first shark scales ever found date back to 450 million years ago, and the first shark teeth to about 410 million years ago, so Phoebodus sharks were pretty early on the shark scene, evolutionarily speaking. They had three-cusped teeth, eel-like bodies and long snouts, and may have looked a bit like modern frilled sharks.

Much of these sharks' biology is known from an almost-complete fossil found in Morocco. They may have hunted by snapping their prey from the water in a quick, deadly bite.

4. Ninja lanternsharks

Credit for these stealthy sharks' common name goes to a couple of 8-year-olds, cousins of the scientist who discovered the creature. According to Hakai Magazine, researcher Vicky Vásquez chose the name ninja laternshark after her young cousins suggested that the sharks' sleek black skin and gentle bioluminescence — which is used to blend in with sunlight filtering down from the ocean surface — reminded them of a "super ninja."

These snazzy-looking sharks have a fun scientific name, too: Etmopterus benchleyi, after Peter Benchley, the author of the book "Jaws" (Doubleday: 1974).

Ninja laternsharks are small, growing to only about 1.6 feet (0.5 m) long. They live off the coast of Central America.

3. Wobbegong sharks

What do you get when you cross a fish with a 1970s area rug? Probably a wobbegong shark. These bottom dwellers from the family Orectolobidae are camouflaged with splotchy orange-ish patterns. The sharks even sport a "frill" in the form of sensory lobes that line their jaws.

There are a dozen species of wobbegong sharks, spread across the eastern Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean. The largest grow to more than 10 feet (3 m) long. "Wobbegong" means "shaggy beard" in an Indigenous Australian language.

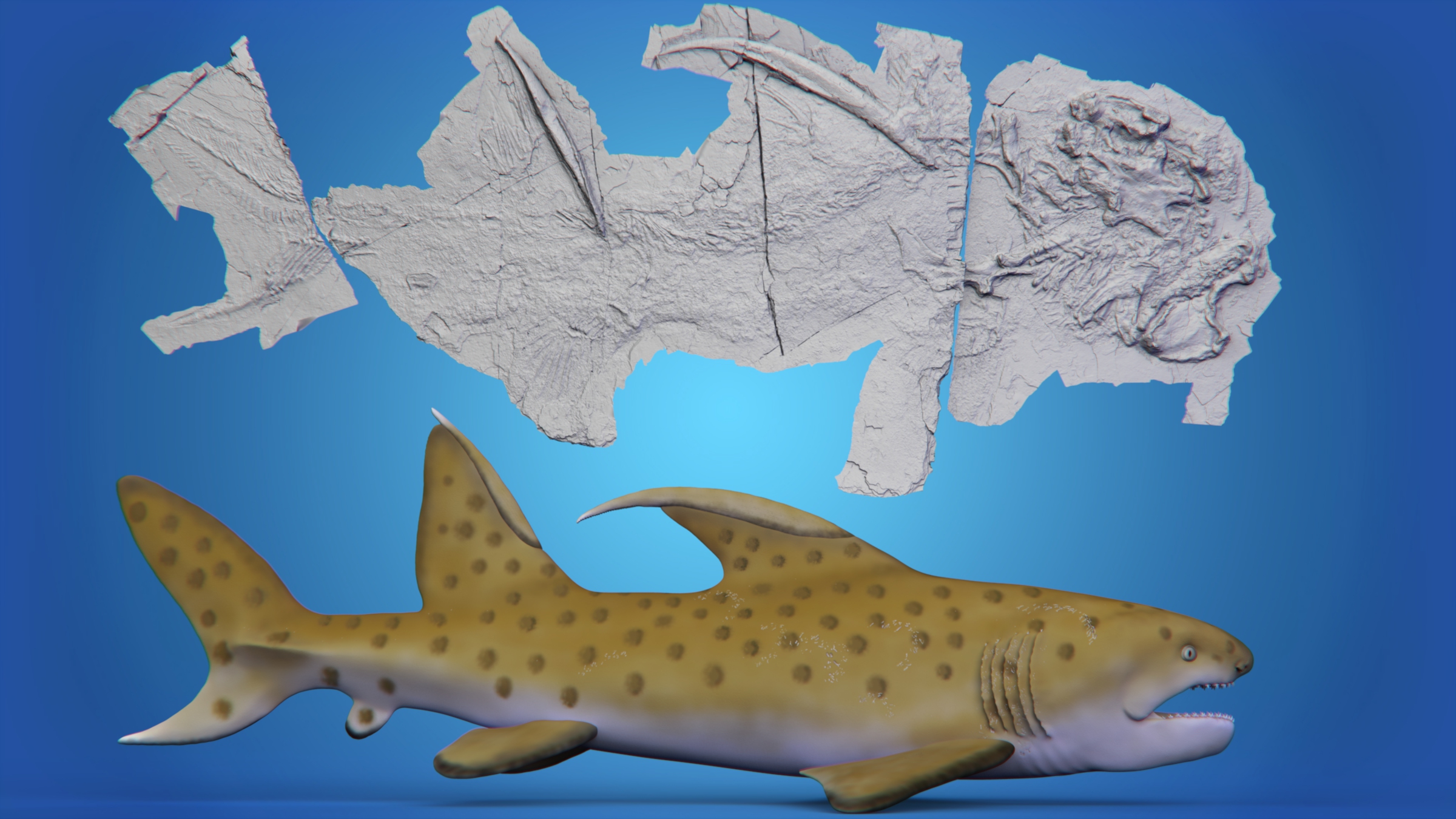

2. Eagle sharks

Sharks used to be even weirder. Ninety-three million years ago, in what is now Mexico, eagle sharks (Aquilolamna milarcae) glided through the sea on fins like wings. And what wings they were: The sharks' fins stretched 6 feet 2 inches (1.9 m) across, making the animals wider than they were long, as they measured 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m) in length.

Though these sharks' teeth did not survive fossilization, their discoverers suspect that they were filter feeders like modern whale sharks.

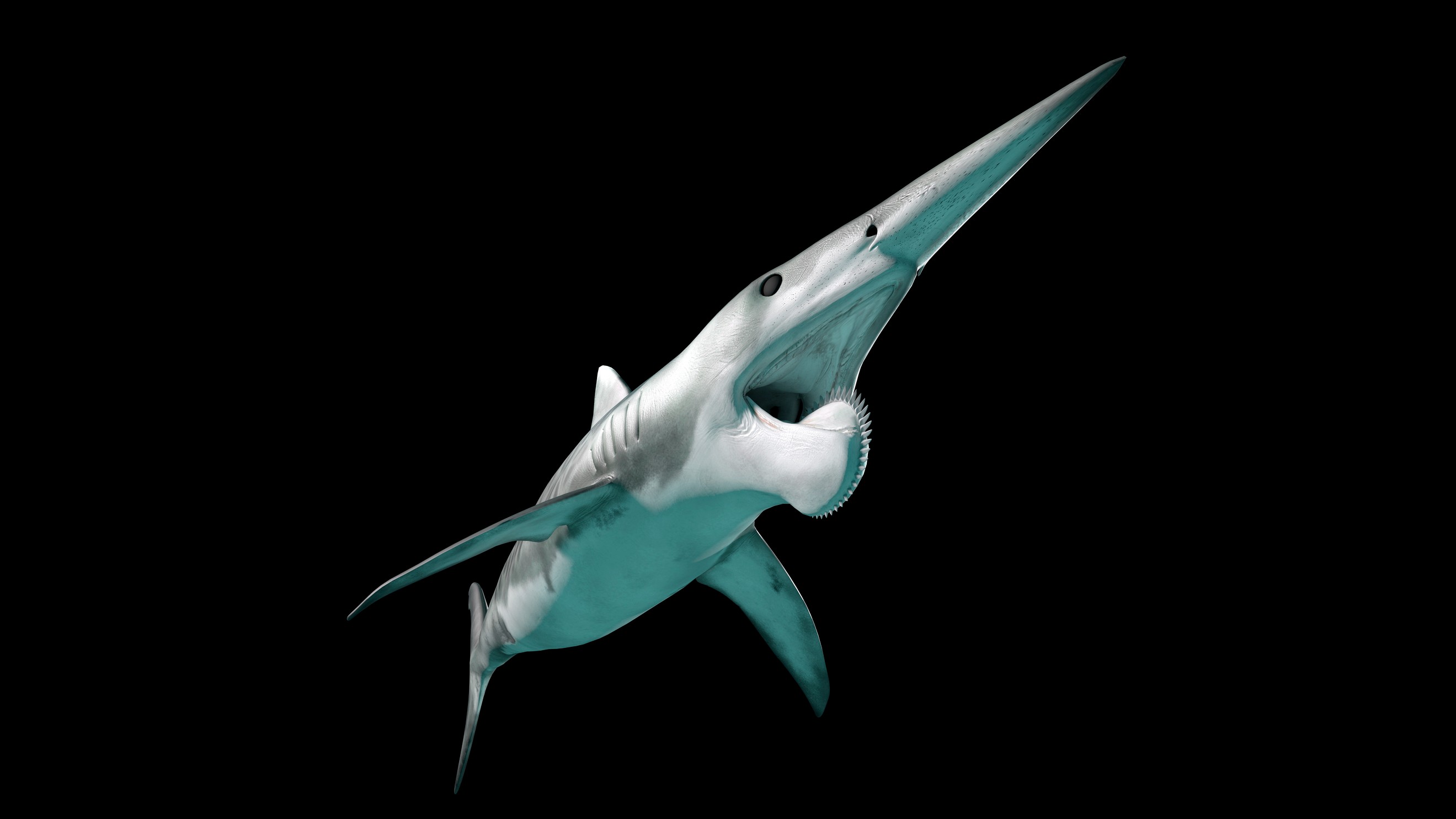

1. Helicoprion sharks

These creatures' bizarre buzzsaw-jaws are so mind-boggling that it took researchers more than a century to figure out what the heck was going on with Helicoprion. The jaws, which look more like spiral snail shells than anything shark-related, were first unearthed in the Ural Mountains in the late 1800s and belonged to an extinct genus that lived around 270 million years ago. A geologist recognized the whorl as teeth and named the creatures that sported them Helicoprion in 1899, according to Wired. But no one could figure out how a shark could fit such a strange saw of teeth into its mouth. Did the saw perhaps fit in the shark's throat? Was it attached to some sort of extendable jaw tentacle that shot out when the animal was attacking?

It wasn't until 2014 that scientists figured it out, based on a specimen found in Idaho that had parts of the upper jaw preserved. It turns out, according to National Geographic, that the whorl of teeth fit into the sharks' lower jaw. The sharks, which grew to 25 feet (7.6 m) long, had no upper teeth to interfere with the buzzsaw arrangement.

The study that nailed down the sharks' saw-tooth arrangement also found that Helicoprion were likely not technically sharks, but close shark relatives called ratfish. But with teeth like that, we're going to let them slide into this countdown anyway.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.