What was the Indus Valley Civilization?

The Indus Valley Civilization arose about 5,000 years ago.

The Indus Valley Civilization is one of the oldest civilizations in human history. It arose on the Indian subcontinent nearly 5,000 years ago — roughly the same time as the emergence of ancient Egypt and nearly 1,000 years after the earliest Sumerian cities of Mesopotamia. The Indus Valley Civilization, in its mature phase, thrived for about 700 years, from around 2600 B.C. to 1900 B.C.

"The Indus Valley Civilization, also called the Saraswati or Harappan civilization, is one of the 'pristine' civilizations on our planet," William Belcher, an anthropologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, told Live Science.

A pristine civilization is one that arose indigenously or independently of other civilizations. More specifically, it is one that developed on its own, without conquest, and without the benefit of cultural exchange or immigration with another established society. Generally, the six pristine civilizations recognized by archaeologists and historians are in the following areas: Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, Mesoamerica (which includes parts of Mexico and Central America), the Andean region and the Indus Valley. These civilizations arose at different times — the earliest of these, Mesopotamia, arose some 6,000 years ago, while the earliest Andean civilization, the Chavin, developed in approximately 900 B.C.

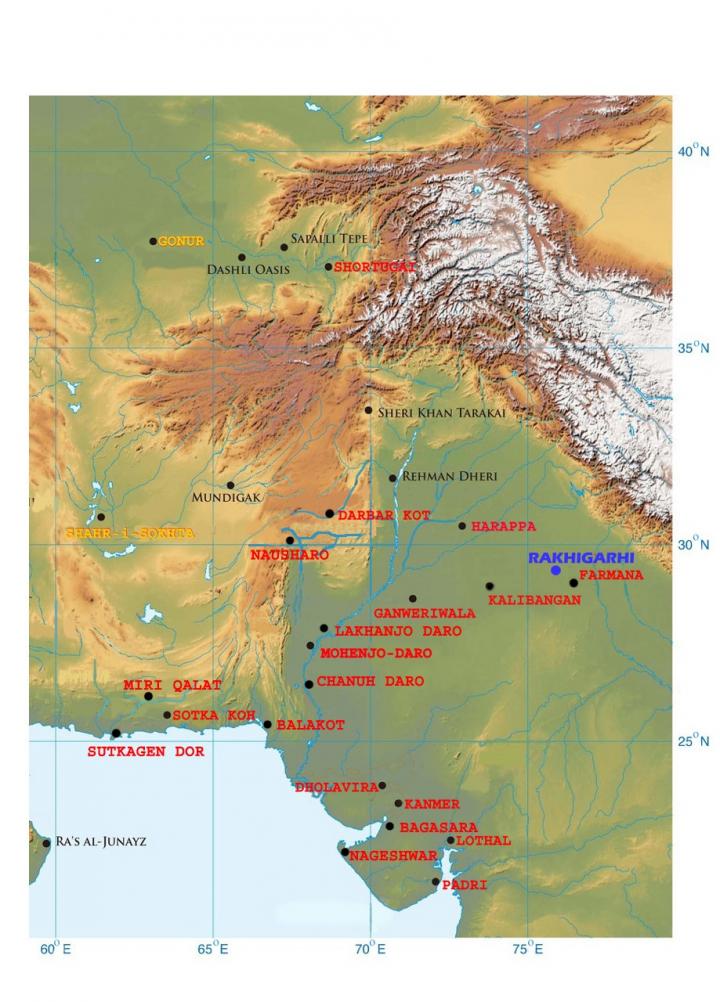

Indus Valley Civilization map and rivers

The Indus Valley Civilization derives its name from the Indus River, one of the longest rivers in Asia. Many of the Indus Valley Civilization's large, well-planned cities, such as Mohenjo-Daro, Kot Diji and Chanhu-Daro, were situated along the course of the Indus River, which flows from the mountains of western Tibet, through the disputed region of Kashmir and southwestward before emptying into the Arabian Sea near the modern city of Karachi, Pakistan. Other Indus Valley Civilization cities were located next to different major rivers, such as the Ghaggar-Hakra, Sutlej, Jhelum, Chenab and the Ravi rivers, or on the alluvial floodplains between rivers. Today, much of this area is part of the Punjab region, which is translated as the "land of the five rivers" in what is now Pakistan. Other Indus Valley Civilization cities are located in northwest India, and a few additional cities are in northeastern Afghanistan, near archaeological sites where tin and lapis lazuli, a blue metamorphic rock, were mined.

"The Indus Valley Civilization covers approximately 1 million square kilometers [386,000 square miles] and extends throughout northwest India, Pakistan and parts of Afghanistan," Belcher said. "This really makes it one of the largest 'Old World' civilizations in terms of geographic extent."

Indus Valley Civilization cities were characterized by sophisticated urban planning and included water control systems and grid-focused neighborhoods, with roads and alleyways laid out on the cardinal directions. Many of the roads were broad avenues that were paved in baked brick with elaborate drainage systems. Although archaeologists don't know the exact number of inhabitants that these cities contained, the larger urban centers, like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, might have had between 30,000 and 40,000 people, or possibly more, Belcher said.

Discovery of the Indus Valley Civilization

"The Indus Valley Civilization first came to the attention of the world through the work of British officer-archaeologists during the mid-1820s," Belcher said.

The first of these, according to World History Encyclopedia, was a man who went by the alias of Charles Masson (his real name was James Lewis). Masson was a soldier of artillery who deserted the British army in 1827 and subsequently roamed the Punjab region. He was an avid coin collector, and he excavated ancient Indian archaeological sites looking for coins. His travels eventually took him, in 1829, to the Indus city of Harappa, in modern-day Pakistan, where he looked for coins and other artifacts. Most of the city was buried by that time, but Masson made a record of the city's ruins in his field notes, which included drawings. Masson had no idea how old the city was or who built it — he attributed it to Alexander the Great, according to World History Encyclopedia.

When he returned to the United Kingdom, Masson published a book called "Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Punjab," which caught the attention of a former British army officer and engineer named Alexander Cunningham, who was the head of the Archaeological Survey of India. Spurred on by Masson's findings, Cunningham excavated at Harappa in 1872 and in 1873 and wrote an extensive interpretation of his findings, though many of his conclusions were speculative and incorrect, Belcher said. For example, Cunningham argued that the city was probably only 1,000 years old, much younger than its real age of 2600 B.C., according to Harappa.com. Cunningham based this conclusion on what local inhabitants of the area told him about the site's traditional folklore. He also argued that the origins of the city were likely due to contact with people from the Near East, possibly the inhabitants of Mesopotamia. He is credited with being the first scholar to discover and comment on the famous Indian seals, which contain the still much-debated Indus Valley script.

A British archaeologist named John Marshall continued the work begun by Cunningham when he became director of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1904. He excavated at Harappa and then later, in 1924, at Mohenjo-Daro ("the mound of the dead" in the Sindhi language), a site that was brought to his attention by local people. Marshall speculated, like Cunningham, that the civilization was likely only perhaps 1,000 years old. But, unlike Cunningham, he noted the many similarities between the archaeological sites of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, and recognized that the two cities were representative of a single culture, which he termed the Indus Valley Civilization.

The first announcement of the discovery of the Indus Valley Civilization was made in the Sept. 20, 1924 issue of the Illustrated London News. Here, some of the first images of the Indus Valley Civilization were portrayed, including brick buildings, a glazed brick shrine and graves.

The Indus Valley Civilization's society and culture

More recent archaeology has fleshed out our understanding of the Indus Valley Civilization, though many questions remain. "We now have thousands of sites," Belcher said, "but few have been excavated in detail."

Despite this dearth of excavations, the few Indus Valley archaeological sites that have been analyzed reveal a complex, urbanized society that was involved in sophisticated urban planning and large-scale building projects (such as large baths and multi-story buildings), as well as numerous crafts, including pottery-making, metallurgy, lapidary (stone and gem) arts and brick-making. Food production was an important endeavor for such a large population, and the Indus Valley people utilized an irrigation system that involved storing water in large tanks to grow several important food crops, including barley, wheat, sesame and various legumes, according to Belcher. Cotton was also an important crop for the civilization's clothing and textiles. The Indus Valley people raised domesticated animals, including cattle, water buffalo, pigs, sheep and goats. The discovery of the bones of ancient wild animals, such as deer and fish, in Indus Valley cities attest to hunting and fishing during the civilization's existence.

Little is known about the political systems of Indus Valley society, though Belcher suggested that a cultural elite may have ruled with enough power and authority to initiate large-scale building projects. However, few elaborate tombs and no definitive temples or palaces have been discovered that are indicative of a distinct authoritarian or royal class.

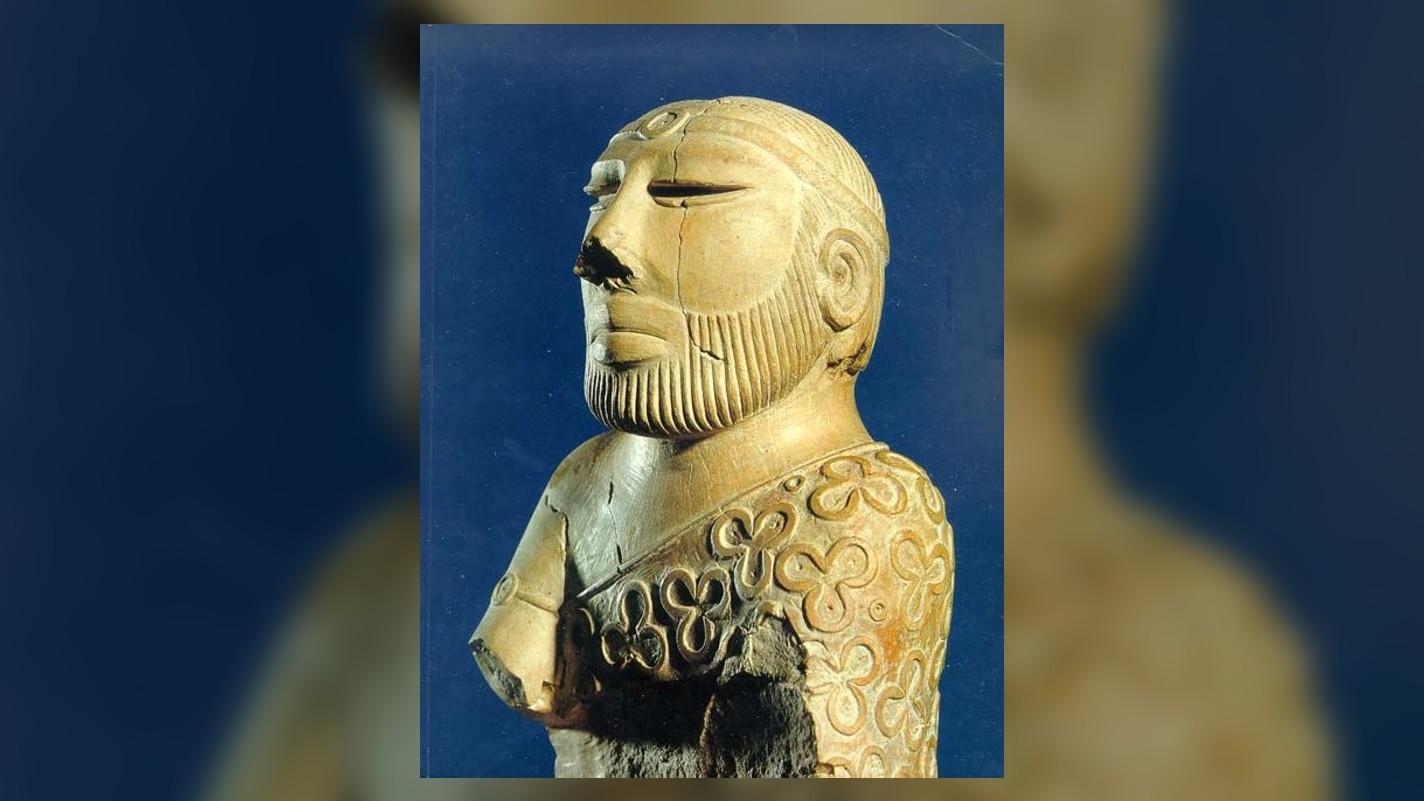

Nonetheless, archaeologists have uncovered some artifacts that could point to a ruling class. For example, a small steatite (soapstone) figurine known as the "priest-king," was found during the excavations at Mohenjo-Daro in 1925, and may represent a member of the ruling class of the city.

Perhaps the most famous structure of Mohenjo-Daro is the so-called Great Bath. It has been interpreted as a communal bath built for ritual purposes, though its actual function remains a mystery, Belcher said. It measures 893 square feet (83 square meters), is 7.9 feet (2.4 m) deep and is rectangular in shape, according to Britannica.

Some scholars have claimed that the lack of evidence of temples and palaces suggest that the Indus Valley Civilization was not actually a state, but was a collection of independent cities whose societies were based on consensual decision-making processes, and that there was no social stratification. However, this viewpoint is debated.

"I doubt this, given the amount of labor that would have been required to make the cities," Belcher said. "The distribution of settlements does suggest that we have a state or a series of smaller city-states. The planning and architecture of these urban centers would definitely have required coordination."

One theory, Belcher noted, was that the society was controlled by a class of merchants. "Some researchers suspect that the society was integrated through a system of rituals and iconography that was manipulated by a class of merchants," he said. "This allowed this class to control specific trade routes and forms of trade goods."

Trade likely played a vital role in Indus Valley society, Belcher said, and there were many long-standing trade networks that connected with areas as far away as Mesopotamia and Egypt, according to World History Encyclopedia. Most of the Indus Valley Civilization's major cities are located at the juncture of several geographic trade routes, Belcher added.

The enigmatic Indus Valley writing system and seals

The Indus Valley writing system has long been a source of great interest, speculation and scholarly work. Scholars first came across the writing system when Cunningham reported finding several seals, or small, square-shaped steatite tablets, at Harappa, on which were inscribed various animal images, such as bulls, elephants and even fanciful creatures. These images were always accompanied with an enigmatic script, made up of circles, crosses, wheel-like signs, parallel lines and numerous other unfathomable designs, which, according to Belcher, has been only partially deciphered. Since Cunningham's discovery, these steatite seals have been found at various Indus Valley sites.

"We believe the writing system is logosyllabic, meaning that each sign represents a sound," Belcher said. "This differs from logographic writing where each sign represents a word."

So far, between 400 and 500 individual signs have been identified, according to Belcher. "The writing probably functioned in much the same way it did in the Near East — for economic purposes and to exhibit ownership, but the structure is completely different [from Near Eastern examples] and it doesn't appear to have evolved much. It probably contains no complete grammar or literary texts," he said.

Ancient DNA

In 2019, an analysis of skeletal remains that are nearly 5,000 years old marked the first time researchers had acquired ancient DNA from an individual who was a part of the Indus Valley Civilization. The remains, belonging to a woman, were found at the Indus Valley site of Rakhigarhi, northwest of New Delhi, according to a study published in the journal Cell. Scientists sequenced a trace amount of DNA from the woman and compared it with the DNA of modern South Asians. The results revealed that the woman was a genetic ancestor of most modern Indians.

"This finding ties people in South Asia today directly to the Indus Valley Civilization," study co-researcher David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, said in a statement at the time.

The skeleton's genome, however, held at least one surprise; although modern South Asians contain the DNA of Steppe pastoralists who lived in Eurasia, the Indus woman doesn't have any such DNA. This suggests that the mixing between Eurasian pastoralists and South Asians, a characteristic of Indians today, likely occurred after the downfall of the Indus Valley Civilization. Moreover, this gives credence to the idea that the Indus Valley Civilization likely arose independently of Near Eastern influence, meaning that the civilizations likely developed farming independently.

The demise of the Indus Valley Civilization

According to World History Encyclopedia, between 1900 B.C. and 1500 B.C., the Indus Valley cities were steadily abandoned, and the people relocated south. Belcher characterized this as a process of "deurbanization," in which the inhabitants of the Indus Valley cities returned to a village-based lifestyle. This development has given rise to much discussion over the decades and has fueled a multitude of theories as to why the culture declined and fell. Some scholars have argued that a decline in trade networks led to this abandonment, while others have suggested that massive flooding played a role in this decline. Another theory posits the idea that the Indus people fell prey to Indo-Aryan invaders from the north who attacked the cities and drove the people south. This theory, once popular, has now been rejected as false, according to World History Encyclopedia.

Modern archaeologists have suggested that a combination of climate change and a change in the course and volume of the rivers — to which the Indus people were largely dependent — likely played the largest roles in the civilization's collapse, a 2012 study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found. This climate change manifested in drier and more arid conditions and a significant drought, a phenomenon known as the 4.2-kiloyear event — a still controversial topic that some scholars have suggested led to the demise of several early civilizations, such as the Akkadian Empire and other Mesopotamian cities.

However, the Indus people did not simply disappear. As the DNA evidence attests, the modern populations of India and Pakistan carry the genetics of these ancient people. "One of the things I think is most intriguing is that the Indus Valley Civilization never really ended," Belcher said.

Additional resources

Watch a video from World History Encyclopedia called "Introduction to the Indus Valley Civilization." Or, read Britannica's article about the Indus Valley Civilization. You can also learn about the ongoing excavations at Rakhigarhi, an Indus Valley civilization site, in the India Times.

Bibliography

Cartwright, M. World History Encyclopedia (2015), Chavin Civilization" Chavin Civilization - World History Encyclopedia

Mark, J. World History Encyclopedia (2020), "Indus Valley Civilization" https://www.worldhistory.org/Indus_Valley_Civilization/.

Stephanie, V. Harappa.com (2014), "The First Images of the Announcement: The Illustrated London News" https://www.harappa.com/blog/first-images-announcement-illustrated-london-news

Mengal, M. World History Encyclopedia (2020), "Priest-king from Mohenjo-Daro" https://www.worldhistory.org/image/12858/priest-king-from-mohenjo-daro/

Handwerk, B. Smithsonian Magazine (2019), "Rare Ancient DNA Provides Window Into a 5,000-Year-Old South Asian Civilization" https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/rare-ancient-dna-south-asia-reveals-complexities-little-known-civilization-180973053/

Shinde, V. et al. "An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers." Cell, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.048

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Garlinghouse is a journalist specializing in general science stories. He has a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of California, Davis, and was a practicing archaeologist prior to receiving his MA in science journalism from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has appeared in an eclectic array of print and online publications, including the Monterey Herald, the San Jose Mercury News, History Today, Sapiens.org, Science.com, Current World Archaeology and many others. He is also a novelist whose first novel Mind Fields, was recently published by Open-Books.com.