What's Inside a Black Hole?

You've managed to travel tens of thousands of light-years beyond the solar system. Bravely facing the depths of the great interstellar voids, you've witnessed some of the most achingly beautiful and outrageously powerful events in the universe, from the births of new solar systems to the cataclysmic deaths of massive stars. And now for your swan song, you're going big: you're about to take a dip into the inky blackness of a giant black hole and see what's on the other side of that enigmatic event horizon. What will you find inside? Read on, brave explorer.

Nearing the monster

First, we need to clear up some definitions. There are many kinds of black holes: some big ones, some small ones, some with electric charges, some without, and some with rapid rotations and others more sedentary. For the purposes of our adventure in this particular tale, I'm going to stick to the simplest possible scenario: a giant black hole with no electric charge and no spin whatsoever. Of course this is decidedly unrealistic, but it's still a fun story with plenty of cool physics to unpack. We can save a more realistic trip for another visit (assuming we'll survive this hypothetical journey into a black hole, which of course we won't).

From a distance the black hole is surprisingly benign. After all, it's just a massive object, pretty much like any other massive object. Gravity is gravity and mass is mass — a black hole with the mass of, say, the sun will pull on you exactly the same as the sun itself. All that's missing is the wonderful heat and light and warmth and radiation. But if you felt like orbiting it at a safe distance, you most certainly could.

But why bother orbiting it when you could go farther in?

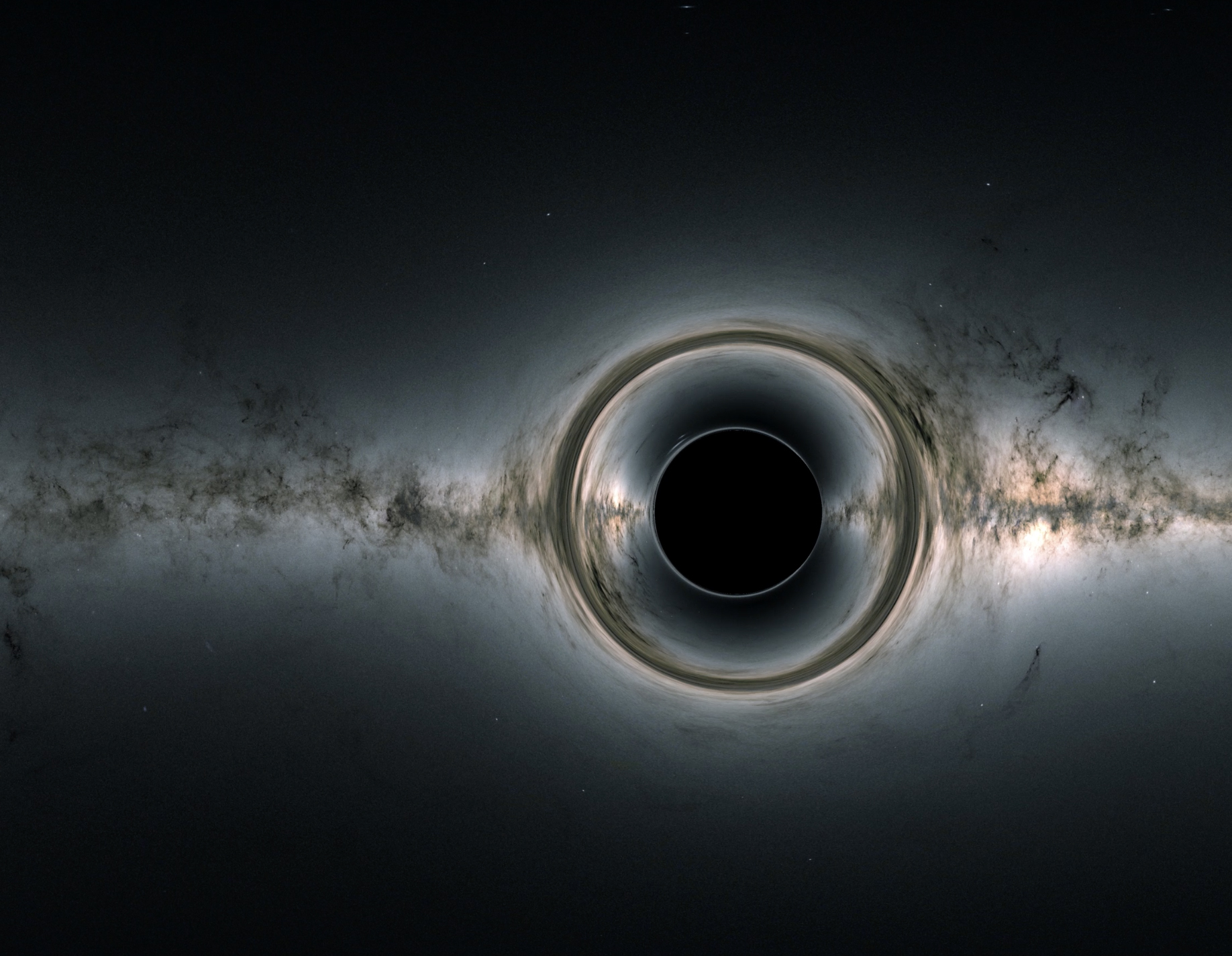

The black hole itself is a singularity, a point of infinite density. But you can't see the singularity itself; it's shrouded by the event horizon, what we generally and wisely consider the "surface" of the black hole. To go farther, you must first pierce that veil.

Beyond the horizon

The event horizon isn't a real, physical boundary. It's not a membrane or a surface. It's simply defined as a particular distance from the singularity, the distance where if you fall below this threshold, you can't get out. You know, no big deal.

This is the distance from the singularity where the gravitational pull is so extreme that nothing, not even light itself, can escape the black hole's clutches. If you were to fall below this boundary and decided you had enough of this black hole exploration business, then too bad. As hard as you fired your rockets, would find yourself no farther from the singularity. You're trapped. Doomed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But not instantly. You have a few moments to enjoy the experience before you meet your inevitable demise, if "enjoy" is the right word. How long it takes to reach the singularity depends on the mass of the black hole. For a small black hole (a few times the mass of the sun counts as "small") you can't even blink an eye. For a giant one, at least a million times bigger than our sun, you have a handful of heartbeats to experience this mysterious corner of the universe.

But hit the singularity you must. You don't get a choice. Within the event horizon, nothing can stay still. You are forever compelled to move. And the singularity lies in all your possible futures.

Outside the black hole's event horizon, you can move in any direction in space you please. Up? Left? A little bit of both? Neither? The choice is yours. But no matter where you do (or don't) go in space, you must always travel into your future. You simply can't escape it.

Inside the event horizon of a black hole, this common-sense understanding breaks down. Here, a single point — the singularity — lies in your future. You simply must travel toward the singularity. Turn left, turn up, turn around, it doesn't matter — the singularity always remains in front of you. And you will hit that singularity in a finite amount of time.

Clock's ticking.

A rendezvous with infinity

As you fall toward the singularity, you're not cloaked in blackness. Light from the surrounding universe fell in with you and continues to fall in after you. Due to the extreme gravity, that light is shifted to higher frequencies, and because of time dilation the outside universe appears sped up, but it's still there.

That's not to say it isn't weird.

Because all the mass of the black hole is concentrated into an infinitely tiny point, the differences in gravity are extreme. You are stretched head to toe in an aptly named process known as spaghettification. And what's more, you're squeezed along your midsection. This squeezing operates on the beams of light surrounding you as well, concentrating the infalling light into a bright band about your waist.

Your view of the singularity becomes grotesque and distorted as well. It's pitch black — you can't see it, because it lies in your future, and just like your future you don't know what it looks like until you get there. But instead of appearing as a tiny point, the huge gravitational differences stretch that point to engulf most of your vision.

As you approach the singularity, it appears as if you're landing on the surface of a vast, featureless, empty, black planet.

When the singularity stretches completely from horizon to horizon, then you've made it.

And what do you find there? We don't know. It would be nice if you could tell us, but like I said, nothing escapes a black hole, including you.

- On the Existence of Black Holes

- Why Are Black Holes So Weird? 'Ask a Spaceman' Explains

- Dream of Visiting a Black Hole? Maybe Don't, Fun NASA Video Suggests

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University, host of Ask a Spaceman and Space Radio, and author of Your Place in the Universe.

Learn more by listening to the episode "What happens when you fall into a black hole?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to Steve B., Martin N., Julius S., Joyse S., Randy W., and John W. for the questions that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.