7 million years ago, our earliest relatives took their first steps on 2 feet

The human-like species walked upright, evidence suggests.

The oldest known human-like species likely walked on two legs as far back as 7 million years ago, a new study finds, and the discovery sheds light on what first set humans apart from our ape relatives.

Researchers analyzed a thigh bone (femur) and a pair of forearm bones (ulnae) from Sahelanthropus tchadensis, which may be the oldest known hominin — a relative of humans dating from after our ancestors split from those of modern apes — according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. First unearthed in Chad in north central Africa in 2001, the remains are about 7 million years old.

The examination of the femur and ulnae indicated that S. tchadensis not only walked on two feet but also climbed trees, adding evidence that this enigmatic species was bipedal, as an earlier analysis of its skull anatomy suggested.

Related: South African fossils may rewrite history of human evolution

Many traits set humans apart from chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest living relatives, such as our big brains, upright postures, opposable thumbs and largely hairless bodies. However, it remains uncertain which of these features began splitting the chimp and bonobo lineage apart from that of hominins, a separation that previous research suggested began happening between 6 million and 10 million years ago.

The partial skull of S. tchadensis that the scientists found revealed that the species was probably close to a chimpanzee in size and structure. Although its brain also appeared chimp-size, its face and teeth more closely resembled those of hominins, suggesting it may have been a close relative of the last common ancestor of humans and chimps, the researchers said.

Judging by the thick, prominent brow ridges of the skull, the specimen, which the researchers nicknamed "Toumaï," was probably male. (In the local Goran language, "Toumaï" means "hope of life." It is a name often given to babies born close to the dry season in the vast, flat, windy Djurab Desert of northern Chad where the fossil was unearthed.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Perhaps the most interesting feature that Toumaï shares with other hominins is the anatomy of the opening at the base of the skull where the spinal cord emerges. In four-legged animals, this opening is normally located toward the back of the skull and is oriented backward. However, in S. tchadensis, this opening is positioned near the middle of the skull and is oriented downward. This suggests that S. tchadensis was bipedal, meaning it walked on two legs, Daniel Lieberman, a human evolutionary biologist at Harvard University who was not involved in the new study, wrote in a commentary published in Nature.

Toumaï lent support to the idea that bipedalism may have helped set the earliest hominins apart from their relatives. However, until now, aside from this skull, researchers knew of S. tchadensis only from a few jaw fragments and some teeth. Without more bones from the rest of the body, some researchers reserved judgment as to whether S. tchadensis was a biped, Lieberman noted.

Ancient leg and arm bones

In the new study, the researchers analyzed three more fossils they associated with S. tchadensis — the femur and two ulnae. The scientists originally recovered these arm and leg bones at the same time and site as the other S. tchadensis fossils. The team associated these remains with S. tchadensis because no other large primate was found in the area, although they said it was impossible to know whether the fossils belonged to Toumaï.

Related: 10 fascinating findings about our human ancestors from 2021

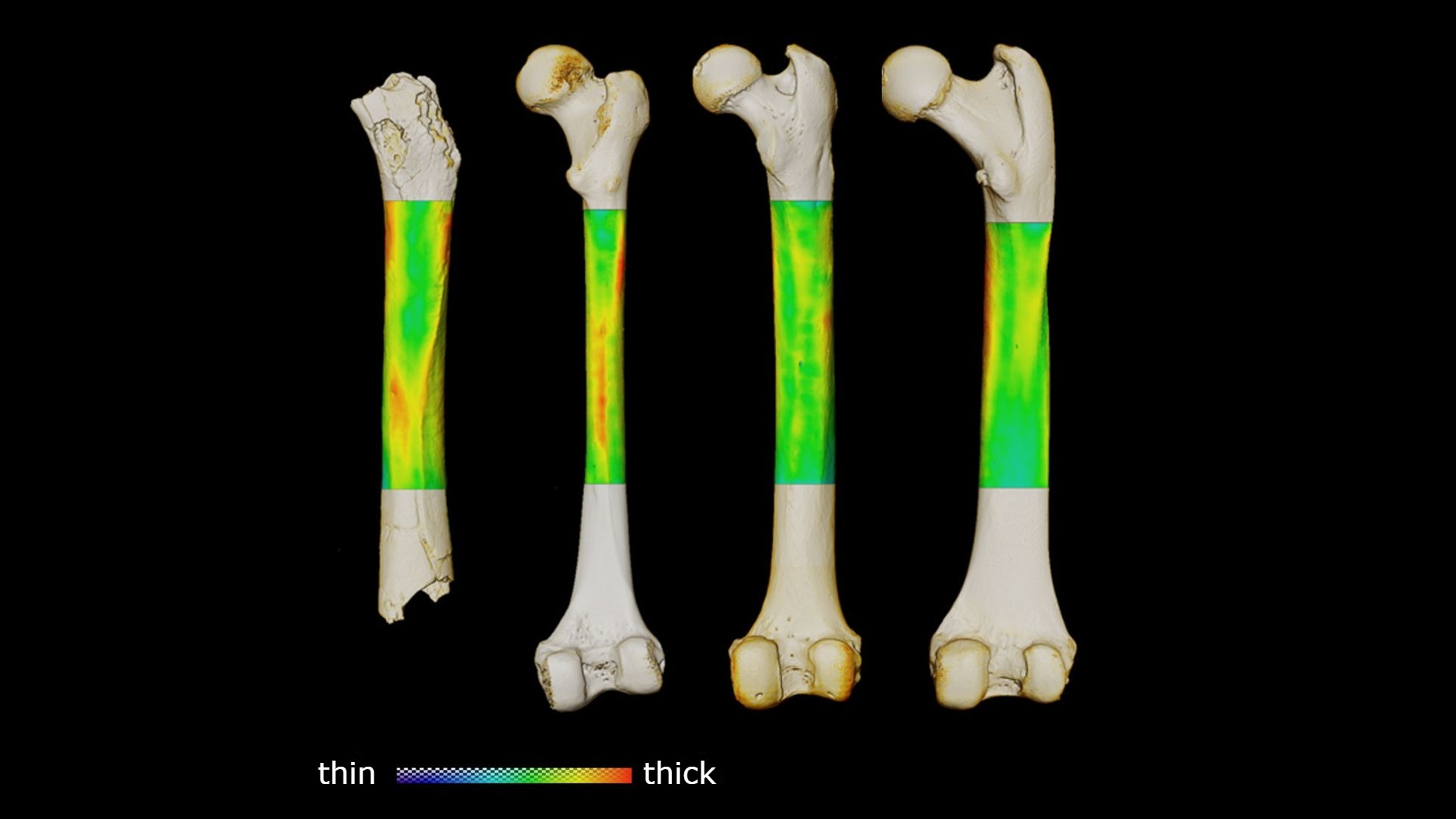

The researchers analyzed both the outside shapes of the bones and their internal microscopic structures. Next, they compared these data with corresponding details from living and fossil species, including chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, extinct apes from the same epoch, modern humans, ancient humans, and hominins such as Orrorin, Ardipithecus and australopithecines (Australopithecus and kin).

The base of the femur's neck appeared to be oriented slightly toward the front of the body and flattened, and the upper part of the thigh bone was also slightly flattened — all traits previously seen in known bipedal hominins. Moreover, the sites at which the muscles of the buttock attach are robust and human-like. And the cross-sectional shape of the thigh bone suggests it could resist the kind of sideways-bending forces seen during walking on two legs.

All of these findings in the femur suggested that S. tchadensis was usually bipedal, perhaps on the ground, or maybe also in the forest canopy.

"Our study shows that the Chadian species has a set of selected anatomical features that clearly indicate that our oldest known representatives were practicing bipedalism, on the ground and on the trees," study co-author Franck Guy, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Poitiers in France, told Live Science.

In contrast, the left and right forearm bones are chimpanzee-like and well adapted to climbing trees; they possess highly curved shafts that suggested the presence of powerful forearm muscles, and the shape of the elbow joints hinted that they could cope with high forces when flexed.

The femur did not preserve the joints at either end, so the key features "needed to prove bipedalism are missing," Lieberman told Live Science in an email. "But they did a good job with what they had available to them."

All in all, "the key finding is that the earliest hominins were bipeds of some sort, reinforcing the evidence that the evolution of bipedalism is what set the human lineage on a separate path from the apes," Lieberman said in the email. "But, like our closest living chimpanzee relatives, early hominins still retained abilities to climb trees."

The scientists detailed their findings online Wednesday (Aug. 24) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.