Who invented chocolate?

The earliest evidence of cacao was found in Ecuador.

Chocolate is a delight whether we're biting into a bar or sipping hot cocoa, but who was the original inventor of this treat?

Although it's now familiar as candy, chocolate's origins are much deeper. The individual who discovered how to make chocolate is lost to time, but it was probably someone in South America thousands of years ago.

The earliest evidence for the use of cacao — the fermented, dried seed of the fruit that grows on the South American Theobroma cacao tree — dates to around 5,300 years ago, from the Santa Ana-La Florida archaeological site in southeastern Ecuador, which is attributed to the Mayo-Chinchipe culture, according to a 2018 study in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. But it's likely the plant was used by people throughout South America long before, as the tree was already outside of its natural range by 5,300 years ago.

However, Indigenous South Americans weren't indulging their sweet tooth; the chocolate that they concocted is very different from the chocolate that most people enjoy today.

Related: Why does eating pineapple make your mouth tingle?

To make chocolate, the large seeds — often called "beans" — of the fruit pods of the cacao tree are fermented in the white fruit pulp that surrounds them. They are then dried, cleaned and roasted, after which the skin of the seed is removed to produce cacao nibs — a very rough form of the final product. The nibs are then ground up, and the cacao mass is often delivered as a liquid — called chocolate liquor — which can be mixed with other ingredients to make commercial chocolate. Chocolate liquor can also be pressed to make its two components, cocoa powder and cocoa butter (cocoa is spelled differently than cacao; it refers to cacao in its processed form.)

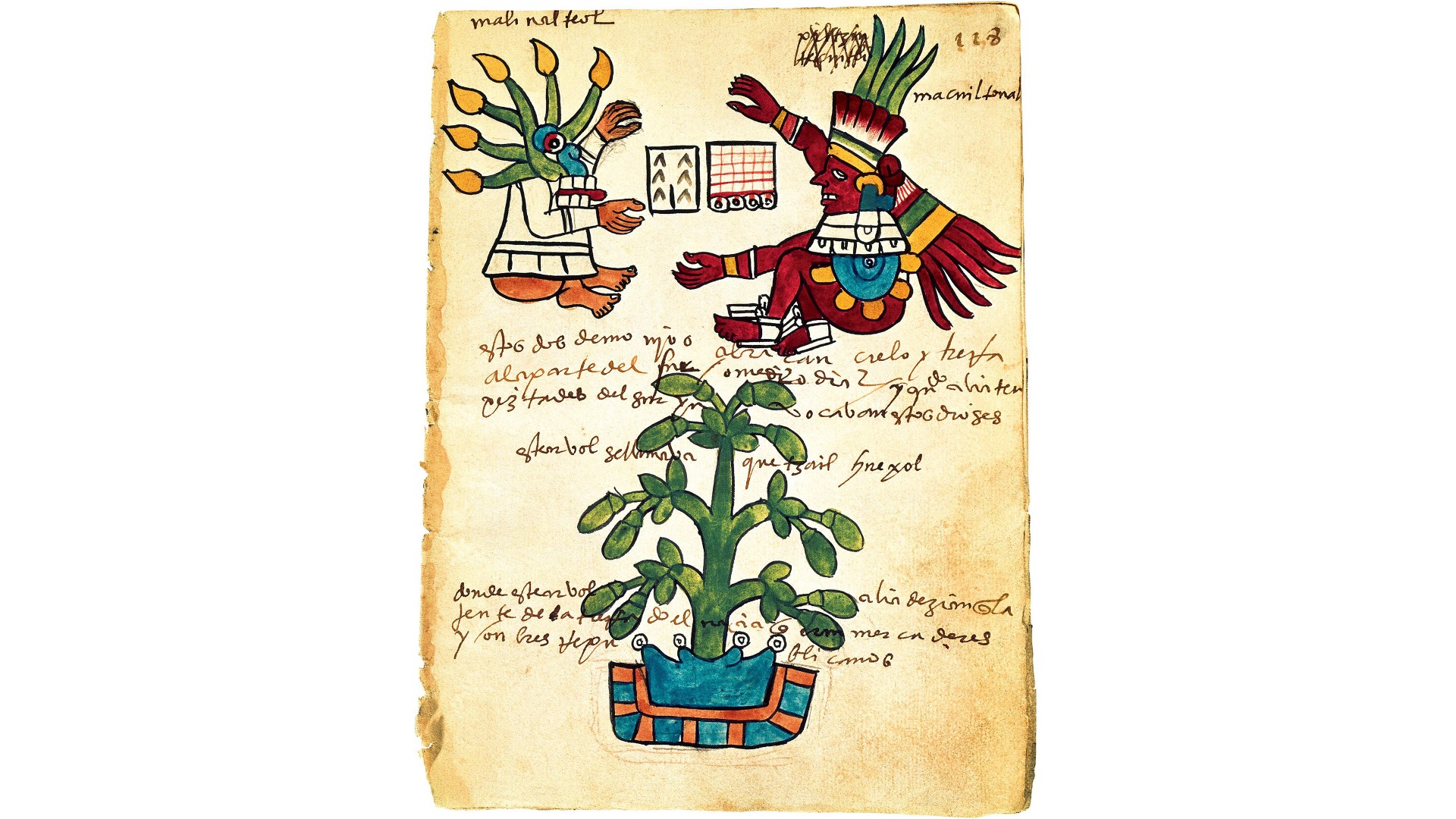

A traditional cacao drink was made by adding ground cacao nibs to water and was typically bitter; it's thought the sugars in the fruity pulp could also be fermented into an alcoholic drink. The frothy mix that resulted was considered both medicinal and an aphrodisiac, according to a 2013 study in the journal Nutrients, and it was highly prized by the elites of ancient societies. According to a Boston University article, the Olmecs — who lived in the south of what's now Mexico between about 1500 B.C. and 400 B.C. — considered cacao a gift from their gods, and that an offering of it connected worshippers with the divine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cacao was grown almost everywhere throughout Central and South America by the time the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the early 16th century A.D., and it's now cultivated in tropical regions around the world. But "the actual point of origin is believed to be the Amazon basin," said Cameron McNeil, an associate professor of anthropology at Lehman College at The City University of New York and an archaeobotanist who has tasted cacao throughout the region.

People had reached the southern tip of South America by about 14,500 years ago (and some controversial sites suggest that the first Americans arrived many thousands of years before that), but it isn't known exactly when the first people arrived in the Amazon, she said.

The first cacao drinks may not have been almost boiling, like hot chocolate today, but rather tepid, McNeil said. "I've traveled all around Mesoamerica sampling traditional cacao beverages, and I would say they're warm, but not hot," she told Live Science. Several Mesoamerican recipes for cacao drinks also use chilies to make them spicy — such as the Maya and Aztec drink xocolatl, which is where the English word "chocolate" comes from — but it's not known who introduced chilies in recipes for these ancient beverages, McNeil said.

Related: Why do some fruits and vegetables conduct electricity?

One reason for the popularity of cacao is that it contains caffeine, the stimulant also found in coffee (coffee and cacao are not related; the coffee plant is native to the Old World, possibly Africa, and not to the Americas). To ancient Americans, the stimulation from cacao was likely subtle but invigorating, McNeil said. And while other stimulants were available in South America, cacao was the only stimulant in Mesoamerica, which may be why it was embraced and became a source of wealth there, she said.

From the 16th century, chocolate was introduced from the New World to Europe as a drink, and it soon became a symbol of luxury. What most of us now think of as chocolate — the chocolate bar — was invented in 1847 by the British company J.S. Fry and Sons, according to The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets.

In 1795, Joseph Storrs Fry patented a method for grinding cocoa beans with a steam engine; his sons later combined cocoa powder, cocoa butter and sugar to make a solid chocolate bar, which became popular in Europe. The company eventually sold several chocolate products — including the first chocolate Easter egg in 1873 — and rival companies such as Cadbury and Rowntree's helped spread the treat throughout the British Empire and beyond. The Swiss were particularly taken with the new chocolate, and in the 1870s the Swiss company Nestlé used powdered milk to produce the first milk chocolate bar.

The first mass-produced milk chocolate bar was sold in the United States in 1900 by Milton Hershey, who had sold caramels before that; and chocolate bars became especially popular in the U.S. in the 1920s, when snacking flourished as drinking alcohol declined due to Prohibition.

Chocolate connoisseurs nowadays can find a wide variety of chocolate to tempt any palate: from sweet and smooth milk chocolate to brittle and bitter 80% to 90% dark chocolate (or even unsweetened baking chocolate, which is 100% cacao). But the next time you partake, just think of the bitter taste and caffeinated buzz that ancient elite Indigenous Americans relished thousands of years ago.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.