Mary Anning: Life and discoveries of the first female paleontologist

Her discoveries shocked the scientific establishment, so why didn't she get credit?

Mary Anning was an impoverished, self-taught fossil hunter whose remarkable discoveries paved the way for modern paleontology. Through her carefully documented finds, she expanded human knowledge of ancient life, although until recently her work was overlooked or dismissed due to her gender and social status.

Early years

Mary Anning was born in 1799 in the seaside resort town of Lyme Regis, England. The town, which billed itself as a budget alternative to resorts such as Bath, had one other feature going for it: its coastline.

Around 200 million years ago, during the Jurassic period, that coastline was covered in a warm sea teeming with prehistoric life, Hakai magazine reports. That sea eventually receded, but the soft sedimentary rocks that formed the seabed remained, and the remains of animals that had been buried in the seabed slowly became stone themselves. Part of the seabed eroded away, forming cliffs; every wave or ferocious storm eroded those cliffs, exposing a cornucopia of fossils.

It's unlikely Anning's parents, Richard and Molly Anning, knew any of this when they moved to Lyme Regis. According to Mary Anning biographer Shelley Emling, Richard, a cabinetmaker, chose Lyme Regis for its potential to attract wealthy tourists wanting to take in the sea air. But he quickly became a beachcomber, selling small fossils to those tourists who wanted a souvenir of their vacations. By the time Anning was 6, she was a regular presence by her father's side, helping him find, excavate and clean fossils.

Tragically, Richard died on Nov. 5, 1810. Emling, who wrote "The Fossil Hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution, and the Woman Whose Discoveries Changed the World," (St. Martin's Press, 2009) says most experts believe his death resulted from a combination of tuberculosis and a fall off the dangerous Lyme Regis cliffs. His death left Molly a widowed mother of two, pregnant with a third child and destitute. To make matters worse, the Annings were "Dissenters," or Protestants that didn't follow the Anglican Church. Their religious practices encouraged Anning to learn to read, but did not necessarily help her status among her neighbors.

Read more: 20 amazing women in science and math

It's not clear, according to Emling, what prompted Anning to go back to the beaches after her father's death. Perhaps she was intrigued by the fossils, or maybe she just missed days hunting for treasures with her father. Other historians, including Hugh Torrens, who studies the history of paleontology in Britain, suggest that in fact Anning's mother continued the fossil business after Richard's death. Either way, Emling writes, a few months after Richard's death, Mary Anning uncovered a large ammonite. A woman, probably a tourist, bought it from her for half a crown, more than anyone had ever paid Richard for a fossil. Once Anning realized she could earn money for her family through fossil hunting, she went to the beach regularly.

First discoveries

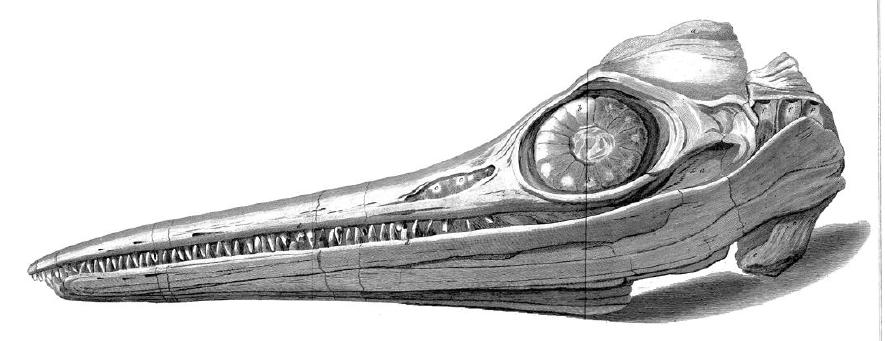

Less than a year later, Anning, with the help of her brother, uncovered a fossil that baffled scientists. It was 17 feet (5.2 meters) long, had 60 vertebrae, and took months to excavate, and by the time the Annings were done, word had spread in town that she had discovered a monster. Part of it looked like a fish, but part looked like a crocodile — something like this had never been seen before, or at least not by the London scientific establishment. It would ultimately be named ichthyosaur, meaning fish-lizard. Ichthyosaur fossils had been found before, but Anning's specimen was the first complete skeleton, and it threw the scientific world into turmoil.

"I by no means consider it as wholly a fish, when compared with other fishes, but rather view it in a similar light to those animals met with in New South Wales, which appear to be so many deviations from ordinary structure," Sir Everard Home, a British surgeon, wrote when first describing the fossil in an 1814 scientific journal. He didn't mention Anning, instead noting the name of the landowner whose estate contained the cliff face.

As Emling writes, many scientists then still believed in the Genesis theory of creation, which didn't allow for evolution or extinction. (Charles Darwin's groundbreaking book, "On the Origin of Species" wouldn't be published for another 48 years.)

Anning had no involvement in the academic excitement around her fossil discovery. She knew, however, that she had found something extraordinary in the ichthyosaur fossil; she sold it to a rich collector for £23. At the time, that sum was enough to feed her family for six months, Emling says. That collector donated the specimen to a private museum; it eventually made its way to the British Museum and finally the Natural History Museum in London where today, only the skull remains.

Read more: The discovery of a gigantic plesiosaur in Antarctica

Anning continued fossil hunting throughout her teenage years. Between 1815 and 1819, Emling writes, she found "several" more complete ichthyosaur skeletons, many of which ended up in local museums or making the rounds on a lecture circuit. Almost unfailingly, the men who lectured about their theories of ichthyosaur anatomy or origin neglected to mention the woman who found, extracted and cleaned the fossils that were making the men so famous.

Anning's next major find was even more controversial than her first ichthyosaur: In 1823, according to a biography published by the UK's Natural History Museum, she discovered the complete skeleton of a plesiosaurus, a four-limbed extinct marine reptile. Just a few years later, in 1828, she also discovered the first pterosaur, a winged reptile that lived during the dinosaur age, to be found outside Germany. In her lifetime, she would go on to discover multiple species of extinct fish as well as a number of other sea creatures. She, along with English paleontologist William Buckland, also pioneered the study of coprolites — fossilized feces.

Scientific recognition at last?

The scientific establishment, which was exclusively male, was slow to recognize Anning's accomplishments. During Anning's lifetime, one of the highest written praises of her was by a woman, Lady Harriet Silvester, a wealthy widow who lived in London, who visited Anning in 1824:

It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour — that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.

It wasn't just her gender, but her lack of formal education, her strong country accent and her poverty that made her easy for academia to ignore. Furthermore, writes Torrens, it was simply more common at the time to record information about the wealthy person who donated a fossil to a museum — fossil hunters in general just weren't people the scientific establishment cared about.

Check out images of researchers unearthing a huge pliosaur in Svalbard, Norway.

Anning did receive some recognition as a fossil hunter, but the evidence points to her having more knowledge than locating and preparing ancient remains. According to Christopher McGowan's book "The Dragon Seekers: How an Extraordinary Circle of Fossilists Discovered the Dinosaurs and Paved the Way for Darwin," (Basic Books, 2001) she read as much scientific literature as she could borrow, and often painstakingly copied the papers out by hand so she could keep copies herself. She also often copied the original drawings. McGowan, a zoologist and vertebrate paleontologist, writes of one paper: "I am hard-pressed to distinguish the original from the copy."

Anning died of breast cancer at age 47 in 1847. The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London published her obituary; it was the first time they had honored anyone who was not a member of the society with such. According to Torrens, the society wouldn't even admit women until 1904 — 57 years later.

Legacy and myths

For a while, because of the lack of recognition paid to Mary Anning by male scientists, Anning was nearly forgotten. But her name is making a comeback. The Lyme Regis Museum, built on the site of Mary Anning's fossil shop, inaugurated a Mary Anning wing in 2017. Two biographies of Anning — Emling's book cited here, and P.M. Pierce's "Jurassic Mary" (Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2006) — within roughly the last decade have introduced more readers to her life. There are also several historical fiction accounts of her life, including "Remarkable Creatures" (Dutton Adult, 2010), and children's books, such as "Dinosaur Lady: The Daring Discoveries of Mary Anning, the First Paleontologist" (Sourcebooks Explore, 2020) and "Stone Girl Bone Girl: The Story of Mary Anning of Lyme Regis" (Scholastic, 1999).

A feature-length biopic released in 2020, starring Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan, means that more people will know Anning's name, if not her accomplishments. In a review in Newsday, critic Rafer Guzmán called the film, which focuses on a romance between Anning and another young woman, geologist Charlotte Murchison, "well-acted erotica, but historically dubious." There is in fact no evidence that Anning was attracted to women. She never married, but in at least one letter, it was Murchinson's husband who Anning found attractive; she called him "certainly the handsomest piece of flesh and blood I ever saw."

An often-repeated myth about Anning is that she inspired the tongue-twister "she sells seashells by the seashore." According to folklorist Stephen Winick, writing for the Library of Congress, there is no evidence for this connection. The first person to make the connection between Anning and the tongue-twister was author Paul J. McCartney in a 1977 book, and even he hedged and wrote that she was "reputed" to be the subject of the tongue-twister.

"I think the most important reason for the Mary Anning [tongue-twister] story's popularity is that it fills a current social need for the recognition of pioneering women scientists…" Winick writes. "The feeling in the culture generally is that women scientists have not been given their due, and that it's our responsibility to remedy that."

Recognition is finally coming for Anning, slowly but surely. At the Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery in England in 2015, according to a report in the BBC, paleontologist Dean Lomax, visiting scientist at the University of Manchester in England, rediscovered an ichthyosaur in the museum's collection that had been mistaken for a plaster copy. According to the 2015 study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, once he and his colleague Judy Massare, a professor emerita in the Earth Sciences Department at The College at Brockport, State University of New York, realized it was a genuine fossil from the Jurassic Coast — and not only that, but a species previously unknown to science — he chose to name it Ichthyosaurus anningae, after Mary Anning.

Additional resources:

- Find out more about the real Mary Anning from the BBC.

- Explore Mary Anning’s ichthyosaur at the University of Oxford Museum of Natural History.

- Read about Mary Anning at the Lyme Regis Museum.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachel is a writer and editor based in Washington, D.C., who covers a range of topics for Live Science, from animals and global warming to technology and human behavior. Rachel also contributes to National Geographic News, Smithsonian Magazine and Scientific American, and she is currently a senior editor at Next City, a national urban affairs magazine. She has an English degree with a journalism concentration from Adelphi University in New York.