Did the Amazon female warriors from Greek mythology really exist?

Is the ancient Greek myth real?

Were the Amazons of ancient Greek mythology — fierce female warriors said to have roamed a vast area around the Black Sea known as Scythia — real? Or were they as fictitious as other Greek myths, such as Aphrodite emerging from genitals thrown into the sea or Jason stealing a golden fleece?

Modern historians assumed that the Amazons, first documented by the poet Homer in the eighth century B.C., were fantasy. But then, in the 1990s, archaeologists began identifying ancient female skeletons buried in warrior graves in the same region.

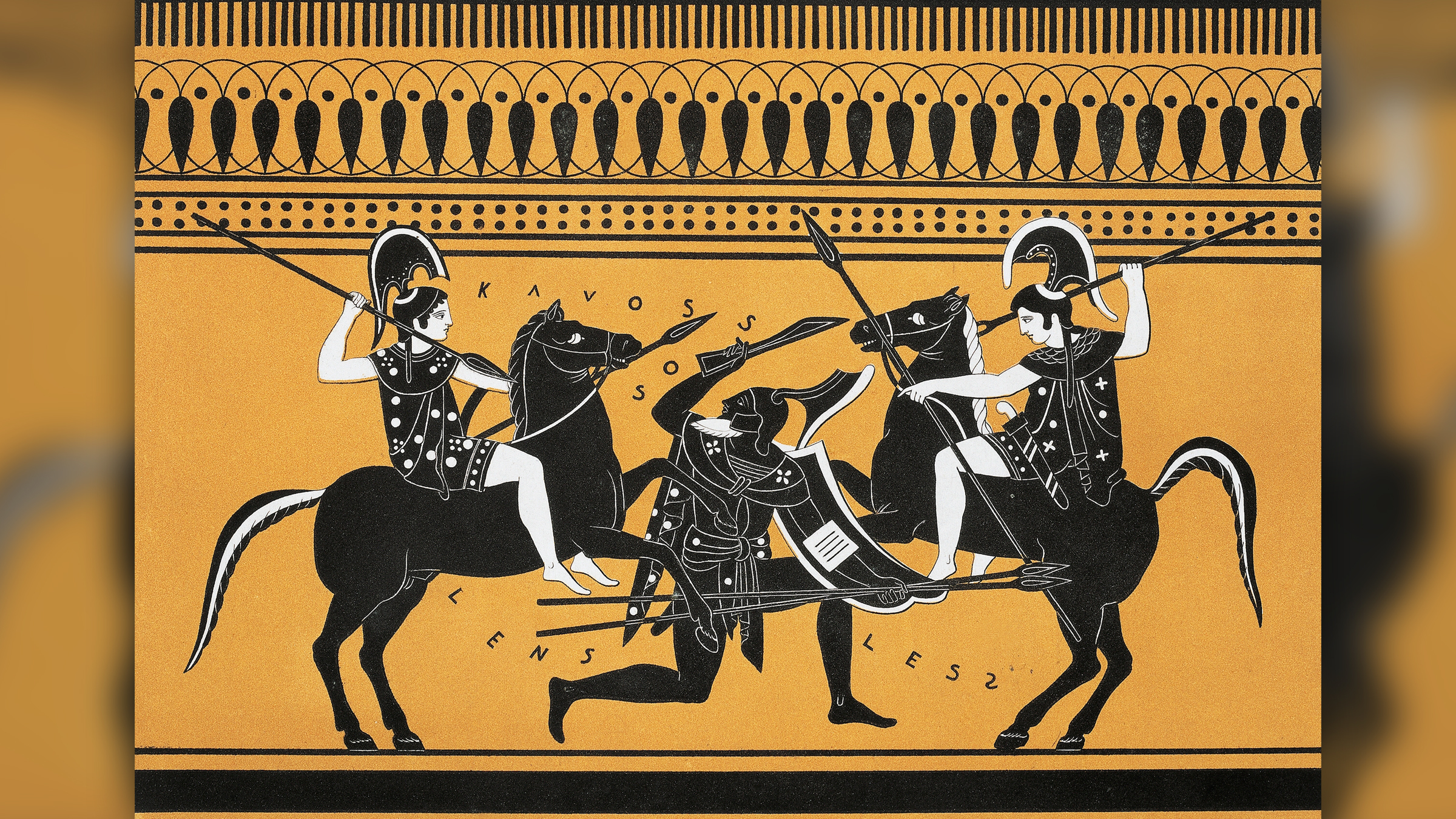

Some skeletons were found with combat injuries, such as arrowheads embedded in their bones, and were buried with weapons that matched those held by Amazons in ancient Greek artwork, according to Adrienne Mayor, a research scholar in the classics department and History of Science Program at Stanford University.

"Thanks to archaeology, we now know that Amazon myths, once thought to be fantasy, contain accurate details about steppe nomad women, who were the historical counterparts of mythic Amazons," Mayor, who is also the author of "The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World" (Princeton University Press, 2014), told Live Science in an email.

Related: Beyond Wonder Woman: 12 mighty female warriors

These nomadic warriors were part of an ancient group of tribes known as Scythians, who were masters of horseback riding and archery. They lived across a vast territory on the Eurasian steppe, stretching from the Black Sea to China, from about 700 B.C. to A.D. 500, Mayor wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine in 2015.

The Scythians were a hard-core people; they had a reputation for drinking excessive amounts of undiluted wine (unlike the Greeks, who mixed wine with water), imbibing fermented mare's milk and even getting high on hemp, according to The British Museum. Frozen bodies of mummified Scythians preserved in permafrost reveal they were heavily tattooed with animals, according to the museum.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scythian societies weren't exclusively women, like in the Greek myth; they simply included female members who lived like the men did. In essence, some (but not all) of the Scythian women joined men in hunting and battle.

"It is exhilarating to know that girls and women on the steppes learned to ride horses and shoot arrows just like their brothers," Mayor told Live Science. She explained that for a small group moving across the harsh steppe lands, under the constant threat of enemies, it made sense for everyone to help with defense and raids, regardless of age or sex.

Active female warriors as young as 10 and as old as 45 have been found in Scythian burial sites, according to Mayor's piece in Foreign Affairs. "So far, archaeologists have identified more than 300 remains of warrior women buried with their horses and weapons, and more are discovered every year," Mayor told Live Science.

The Scythians were not the only group to have women participate in warfare and hunting, and the Greeks were not the only people to tell stories about the Amazons and Amazon-like women.

"There were exciting stories — some imaginary and some based in reality — about Amazon-like women from ancient Rome, Egypt, North Africa, Arabia, Mesopotamia, Persia, Central Asia, India [and] China," Mayor said. "And women who went to war have existed in cultures around the world, from Vietnam to Viking lands, and in Africa and the Americas."

The name of the Amazon river in South America is linked to one such story. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the Spanish soldier Francisco de Orellana — credited as the first European to explore the Amazon, in 1541 — gave the river its name after reportedly being attacked by female warriors whom he compared to the mythological Amazon warriors we now know are based on the Scythians.

Originally published on Live Science.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.