Who were the ancient Persians?

The Persians' empire was one of the largest in the ancient world.

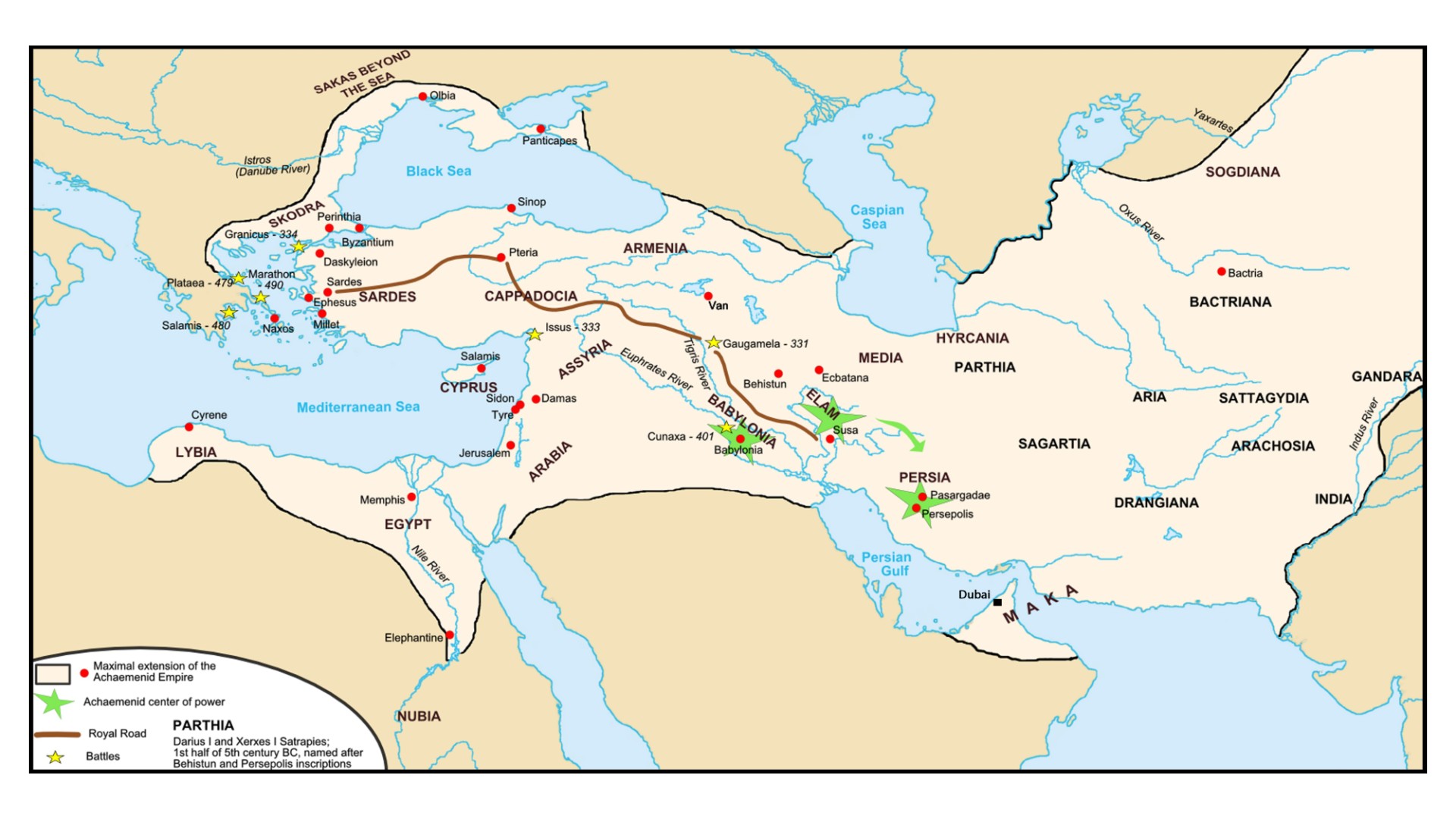

The Persians, the ancient inhabitants of what is now Iran, created one of the ancient world's largest and most powerful empires that flourished from 550 B.C. to 330 B.C. At its height, the Persian Empire, also known as the Achaemenid Empire, stretched from the eastern Mediterranean Sea to the western border with India and included a diverse array of cultures and ethnic groups. It was finally conquered by Alexander the Great during his invasion of Asia in the fourth century B.C.

"The Achaemenid Empire was something drastically different from its predecessors," said Touraj Daryaee, the Maseeh chair in Persian Studies and Culture at the University of California, Irvine, and the editor of "Excavating an Empire: Achaemenid Persian in Longue Dureé" (Mazda Publishers, 2014). "It was the first world empire. It's an Afro-Eurasian empire because it included parts of Africa, Asia and Europe."

Who were the ancient Persians?

The ancient Persians were an Indo-Iranian people who migrated to the Iranian plateau during the end of the second millennium B.C., possibly from the Caucasus or Central Asia. Originally a pastoral people who roamed the steppes with their livestock, they were ethnically related to the Bactrians, Medes and Parthians. In the fifth century B.C. the Greek historian Herodotus described them as being divided into several different tribes, the most powerful of which was the Pasargadae, of whom the Achaemenid clan was a part.

"We first hear of the Persian people from Assyrian sources," an ancient ethnic group indigenous to the Middle East, Daryaee told Live Science.

The ninth-century B.C. Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III, recorded encountering a people who were settled in the area that is now southwestern Iran and went by the name Parsua. This reference, written in cuneiform, appears on his "Black Obelisk," which was found in 1846 and commemorates and records Shalmaneser III's deeds and military campaigns. Scholars suggest the limestone obelisk was probably engraved in 825 B.C., according to the British Museum. The translated reference to the Persians reads as follows:

"Moving on from the land Namri, I received tribute from twenty-seven kings of the land Parsua. Moving on from the land Parsua I went down to the lands Mēsu, Media (Amadāiia), Araziaš, (and) Harhār, (and) captured the cities Kuakinda, Hazzanabi, Esamul, (and) Kinablila, together with the cities in their environs."

The Persian Empire, rise and fall

By the first millennium B.C., the Persians were well established in southwestern Iran, with their capital at Anshan, an old city of the Elamites, an ancient ethnic group from the Iranian plateau. The Persians were ruled by kings who claimed descent from a semi-mythical king named Achaemenes. For several centuries, the Assyrians and later the Medes, an Indo-Iranian people who were settled in northwestern Iran, dominated the Persians, according to World History Encyclopedia. But during the mid-sixth century B.C., an ambitious and capable ruler named Cyrus came to power. Later known as Cyrus the Great, he revolted against the Medes, conquered them, and then embarked on a campaign of conquest, adding the kingdoms of Lydia, Elam and Babylon to his burgeoning empire. At the time of his death in 530 B.C., his Achaemenid Empire stretched from the Balkans in Europe to India, and, as previously discussed on Live Science, is considered to have been one of the largest empires, both geographically and in terms of population, in the ancient world.

Herodotus is one of the main sources of information on Cyrus's life. In Book I of his Histories, Herodotus depicted the early life of the Persian king, recounting in mythological terms how a series of dreams led Astyages, the king of the Medes, to attempt to kill the infant Cyrus. But Cyrus survived these murder attempts, grew into manhood and overthrew the Medes. According to Britannica, this story of Cyrus's infancy is likely a fabricated tale designed to show that Cyrus's reign was destined and ordained.

Xenophon, a Greek soldier and writer (c. 430 B.C. to 350 B.C.), is another important source of information on Cyrus's life, according to Britannica. In his work on Cyrus, called the Cyropaedia, he described the Persian king as "the most handsome in person, most generous of heart, most devoted to learning, and most ambitious, so that he endured all sorts of labor and faced all sorts of danger for the sake of praise."

In addition to being a successful general, Cyrus proved to be a successful administrator and was known for his benevolent nature and generosity, Daryaee said. Cyrus was famous for showing mercy to the nations he conquered, allowing them to retain their own traditions, religions and rights instead of forcing his subjects to adopt his culture (like most other ancient rulers). In the Hebrew books of Isaiah and Ezra, for example, Cyrus is revered as a liberator and is responsible for freeing the Jews from the Babylonians and helping them rebuild the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

This sense of justice and mercy might have stemmed from Cyrus's childhood experiences and the place he grew up, Daryaee noted. "Cyrus was brought up in a multicultural setting in the city of Anshan," he said. "He was privy to all these different religions, cultures and languages. This gave him a great understanding about how to deal with people."

Cyrus realized that to successfully rule a vast empire, a ruler needed to exercise a certain amount of benevolence and understanding, Daryaee said. The Persians had learned from the Assyrian and Babylonian empires that terror and intimidation were not successful long-term strategies. Instead, Daryaee said, the Persians were guided by the concept of "vispadana," a term that is translated as "many people." Vispadana is the recognition not only that the empire is composed of many different cultures but that those cultures are, in fact, a benefit to the empire because of the different skills and capacities their people possess.

"When we compare the Assyrian Empire, which was the preceding empire, we see that the king is depicted as a great conqueror," Daryaee said. "But if you look at the royal carvings at Persepolis, you are getting a completely different perception of how things should be."

Parts of Persepolis, the ancient capital of the Achaemenid Empire, which is near modern-day Shiraz, Iran, are protected today as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site. Several murals found at Persepolis depict the Persian king as a uniter. His subjects, the representatives of many different nations and cultures, are arrayed around him in thankful poses rather than portrayed as captives or victims. "His subjects, such as Medes, Persians and others, are holding hands," Daryaee said. "It's an acknowledgement that this is a multicultural, multi-lingual empire."

Cyrus's son Cambyses II added ancient Egypt to the empire but proved to be a less-capable ruler than his father. After his death, which is attributed to an accident during his Egyptian campaign, Cambyses' younger brother Bardiya ascended the throne, according to Britannica. His reign was short-lived, however; soon after becoming king he was assassinated in 522 B.C. by a Persian noble named Darius, who subsequently took the throne.

The Achaemenid Empire then reached its zenith under Darius. He consolidated the Egyptian conquests and added parts of India and Thrace (in the Balkans) to his empire. He also reformed the empire’s legal code, initiated several massive building projects, created a postal service, and standardized the Persian system of weights, measurements and currency, according to World History Encyclopedia.

The Greco-Persian Wars

It was also during Darius' reign that the famous Greco-Persian Wars began. These were a series of wars that pitted several Greek city states, most prominently Athens and Sparta, against the Persian Empire. The first phase began when a few Anatolian Greek cities, such as Miletus, revolted against the Persians. Athens and Eretria supported the revolt, but it ultimately proved unsuccessful. In retaliation, Darius sent an army to punish those Greek cities. Darius's forces burned the city of Eretria but were defeated in 490 B.C. at the Battle of Marathon by a force of Athenian hoplites (heavily armed foot soldiers) who, though outnumbered, managed to outflank the Persian force.

Darius' son Xerxes continued the war his father had prosecuted; he amassed a huge war fleet in 480 B.C. and invaded Greece in what was known as the Second Greco-Persian War. But like the first endeavor, this invasion also ended in Persian defeat. Darius' fleet was destroyed by the Athenians at the Battle of Salamis, and then later his land forces were defeated at the Battle of Plataea by an army of allied Greek cities led by Sparta, according to the World History Encyclopedia.

The end of the Persian Empire

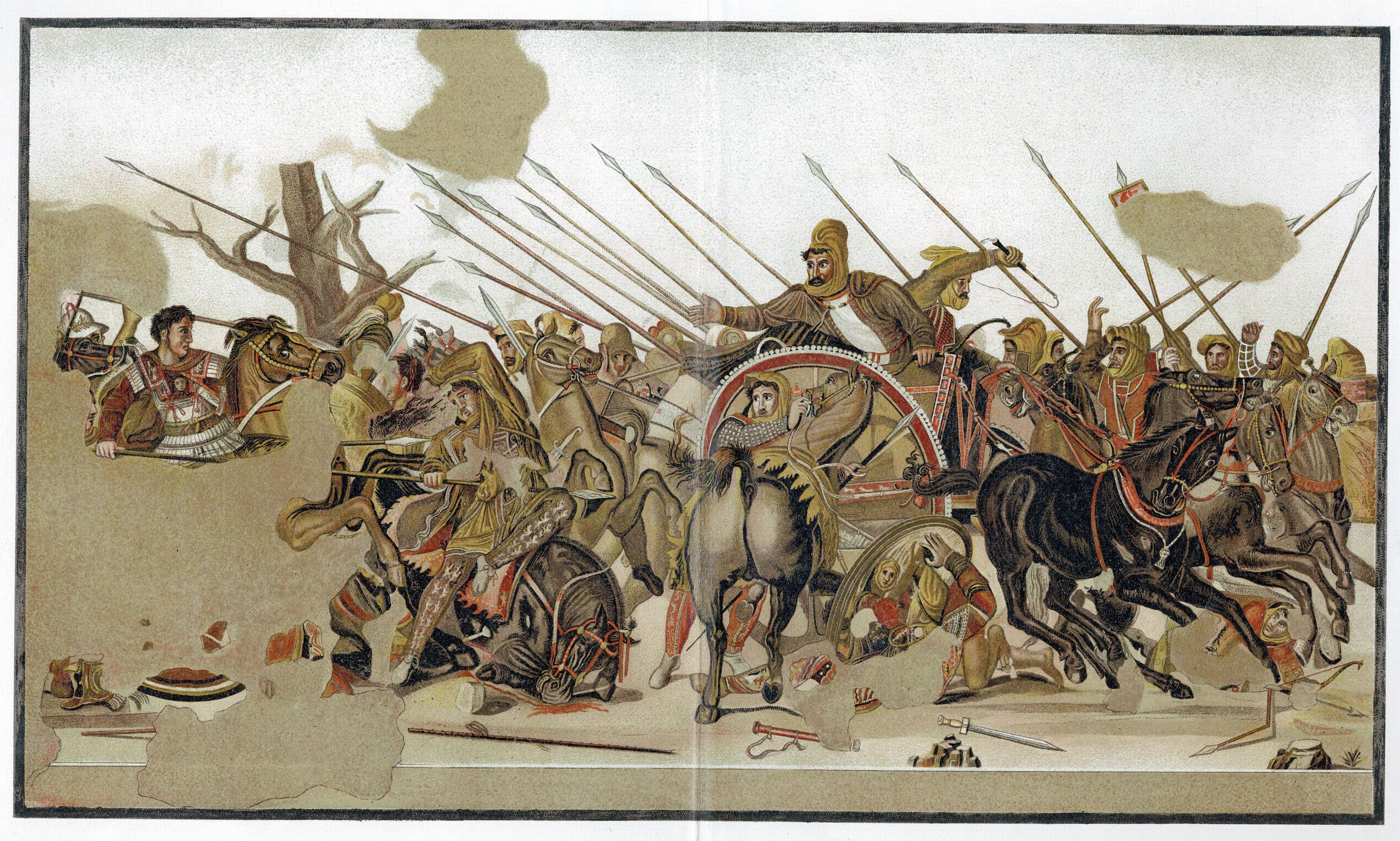

In 334 B.C., the young Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great crossed the Hellespont (today known as the Dardanelles Strait in Turkey) and invaded the Persian Empire. In a series of brilliantly planned and executed battles, the young king defeated the armies of the Persian king, Darius III. Alexander went on to burn Persepolis, but in a stunning change of heart, he gave the fallen king a magnificent burial and married his daughter Stateira, according to Ancient Origins. From then on, Alexander adopted many Persian customs and affectations, such as dressing in Persian clothes. This stance put him at odds with many of his Greek and Macedonian compatriots. He also kept the Persian administrative system intact, according to Britannica, and ordered many of his Macedonian officers and generals to take Persian wives in order to forge a union between the two cultures.

When Alexander died in 323 B.C., his empire was divided among his generals. Much of the former Persian Empire came under the influence of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms, according to Britannica. However, native Persian rule was eventually restored in the second century B.C. under the Parthians.

Additional resources

- Watch a video about the Persian Achaemenid Empire (550 B.C to 330 BC).

- Read National Geographic magazine's article about Cyrus the Great.

- Learn about the polytheistic ancient Persian religion.

Bibliography

University of Chicago, "Herodotus, Book I: Chapters 45-140." https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Herodotus/1b*.html

Archive.org, "Assyrian rulers of the early first millennium B.C., 858-754 B.C." https://ia801602.us.archive.org/15/items/AssyrianRulersOfTheEarlyFirstMillenniumBc858-754Bc/A._Kirk_Grayson_Assyrian_Rulers_of_the_Early_FirBookFi.org.pdf

Britannica, "Elam." https://www.britannica.com/place/Elam

Britannica, "Cyrus the Great." https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cyrus-the-Great

Britannica, "Xenophon, Greek Historian." https://www.britannica.com/biography/Xenophon

Iran Chamber Society, "Cyropaedia of Xenophon; The Life of Cyrus the Great." https://www.iranchamber.com/history/xenophon/cyropaedia_xenophon_book1.php

World History Encyclopedia, "Darius I." https://www.worldhistory.org/Darius_I/

Live Science, "Sixteen epic battles that changed history." https://www.livescience.com/42716-epic-battles-that-changed-history.html

Britannica, "Xerxes." https://www.britannica.com/biography/Xerxes-I

World History Encyclopedia, "The Battle of Salamis." https://www.worldhistory.org/Battle_of_Salamis/

Live Science, "Alexander the Great: Facts, biography and accomplishments." https://www.livescience.com/39997-alexander-the-great.html

Britannica, "Alexander the Great: King of Macedonia." https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alexander-the-Great

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tom Garlinghouse is a journalist specializing in general science stories. He has a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of California, Davis, and was a practicing archaeologist prior to receiving his MA in science journalism from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has appeared in an eclectic array of print and online publications, including the Monterey Herald, the San Jose Mercury News, History Today, Sapiens.org, Science.com, Current World Archaeology and many others. He is also a novelist whose first novel Mind Fields, was recently published by Open-Books.com.