Why are kids such fast learners?

Most young children can easily pick up languages and learn immense amounts of knowledge in their early years. How do they pull this off?

One day, they're a wobbly mess; the next, they're running through the halls. Or their gibberish turns to full sentences seemingly overnight. Children undoubtedly develop new skills quickly, all while learning how to effectively navigate a world that is strange and new to them. Adults, by contrast, may take many years to learn a new language or master certain elements of mathematics — if they do at all.

So, why do children learn so quickly? Is it simply a necessity, or is a child's brain more capable of taking in new information than an adult's brain is?

"It is a common way of thinking that 'children are like sponges' and have the magical ability to learn new skills faster than an adult, but there are some misconceptions here," Debbie Ravenscroft, a senior lecturer in early childhood studies at the University of Chester in the U.K., told Live Science in an email. "A child's cognitive development is age-related and, naturally, children perform worse than their older peers in most areas. However, there are times when being young confers an advantage, and this clusters around their earliest years."

This advantage is largely due to neuroplasticity, meaning the brain's ability to form and change its connections, pathways and wiring based on experiences. Neuroplasticity is what gives children the capacity to learn — and, if necessary, unlearn — habits, routines, approaches and actions very quickly. This ability is most constant and rapid before a child's fifth birthday, when much of what they encounter or experience is novel.

"This [ability to learn quickly] is connected to several areas, including plasticity, their experiences with adults, their environment, and their biological drive to explore," Ravenscroft said. "Childhood is a place where children spend their time catching up with adults' more sophisticated abilities."

Related: Can you learn to wiggle your ears?

Language acquisition, in particular, is an area where children often have a huge advantage over adults, Ravenscroft noted. This is largely because "babies are able to tune in to the rhythm and sounds used in their native language, and can therefore become competent and fluent speakers by the age of four." This ability can help young children learn a second or third language with apparent ease, Ravenscroft said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a research paper published in April 2022 in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, the authors suggest that "human infants are born seeing and hearing linguistic information that older children and adults miss, although they lose this ability with more experience in their environments." Moreover, infants can "discriminate speech sounds and tones used in all of the world's languages, making them open to all input, regardless of the linguistic environment they are born into."

With language acquisition, time is an important variable. "If a child is not exposed to certain sound aspects of language by puberty, for example, it becomes impossible to discriminate between them," Ravenscroft said.

Studies have found that, from birth to puberty, children are capable of learning language rapidly and effectively because of both their neuroplasticity and their "cognitive flexibility," or the ability to mentally switch between two different concepts or ideas rapidly, as well as being able to clearly think about numerous concepts at the same time.

But what about skills other than language learning?

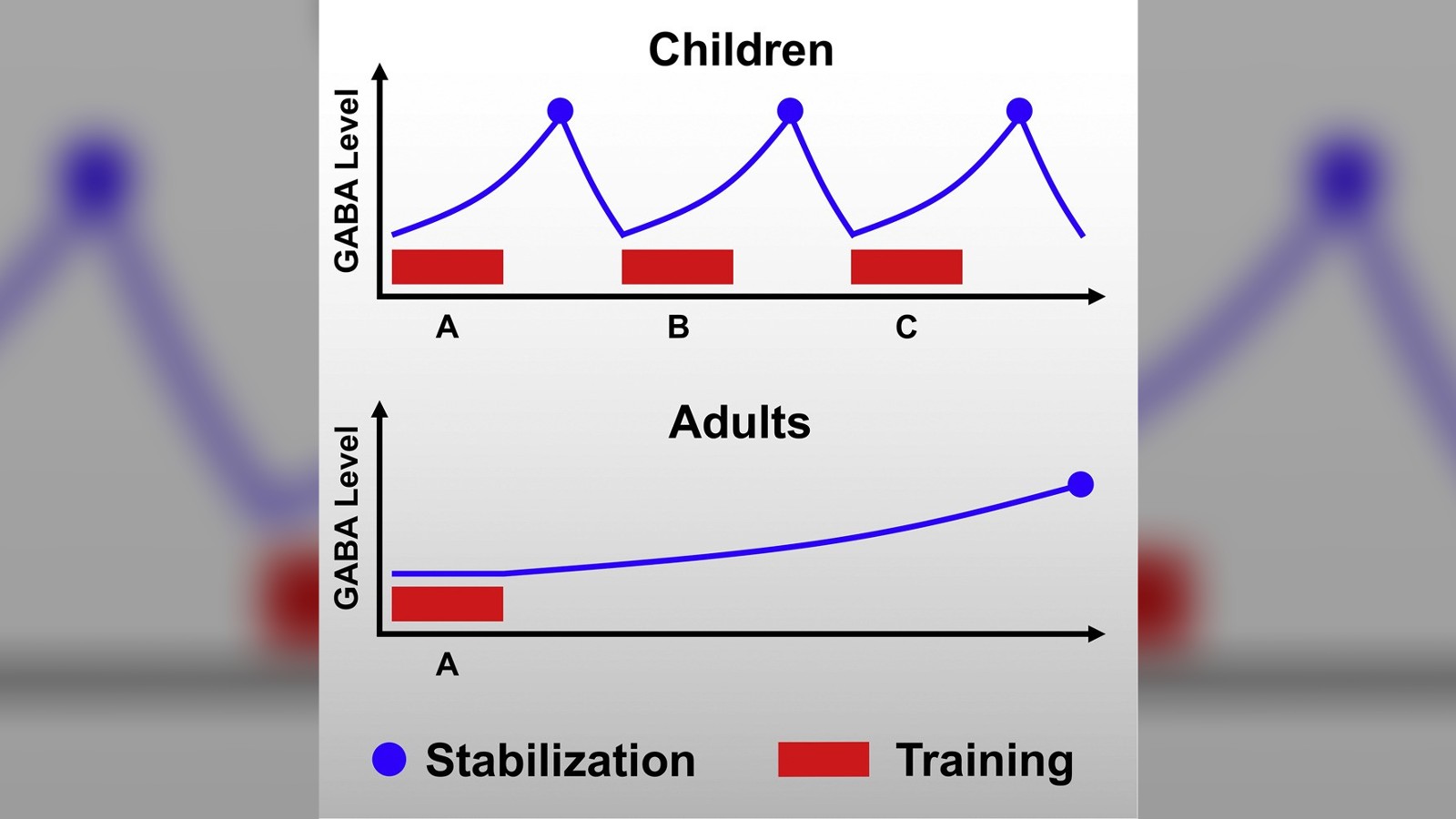

A 2022 study in the journal Current Biology suggests that children and adults exhibit differences in a brain messenger known as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which the research suggests stabilizes newly learned material.

The study found that children have a "rapid boost of GABA" when they participate in visual training and that this learning continues even once the training has concluded, whereas "the concentration of GABA in adults remained unchanged," the researchers wrote in the study. The findings suggest that children's brains respond to training in a way that allows them to more quickly and efficiently stabilize new learning. Consequently, the research supports the idea that children can acquire new knowledge and skills more rapidly than adults can.

"Our results show that children of elementary school age can learn more items within a given period of time than adults, making learning more efficient in children," Takeo Watanabe, co-author of the study and a professor of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences at Brown University, said in a statement.

To learn quickly, however, children also need support, guidance and access to appropriate learning materials.

"While children do have the capacity to learn quickly, they will find challenges if they are not well supported by caring and compassionate adults who shape their environment and experiences," Ravenscroft said. "The best time for learning is as early as possible; reading to a baby offers a wonderful, shared bonding experience in addition to providing a love of language and ensuring connections are made in the early brain."

Birth to age 5 is a "critical period" for children, Ravenscroft added. During these early years, a young child's brain is much busier than an adult's because the child is continually learning and figuring out the best way to approach and navigate any given situation. A child's ability to learn and understand, therefore, is linked to these interactions.

"Very young children, for example, may have difficulty in self-regulating their emotions; but this is typical behavior, as the social brain develops almost entirely postnatally, and does not begin to mature until toddlerhood," Ravenscroft said. "What is needed is time for children to process and accept new knowledge and learning. In an endeavor to speed up children's learning, we can be guilty of rushing, whereas an environment which fosters a child's pace of learning offers so much more opportunity for children to develop a love of interacting with people and places, and engaging in active learning."

Joe Phelan is a journalist based in London. His work has appeared in VICE, National Geographic, World Soccer and The Blizzard, and has been a guest on Times Radio. He is drawn to the weird, wonderful and under examined, as well as anything related to life in the Arctic Circle. He holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Chester.