Why are sexually transmitted infections on the rise in the US?

Surging STIs are being driven by a "perfect storm" of factors in the U.S.

Rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as syphilis, have been rising over the past few years in the U.S. But why are STI rates surging now, and what can be done to reverse that trend?

Reduced public health focus on sexual health has been a big factor in rising STI rates, experts told Live Science.

"Increasing opioid use, COVID-19, and the mpox outbreak have exacerbated a lack of funding and resources in sexual healthcare, creating a perfect storm that's driving up cases in recent years," Casey Pinto, an associate professor of public health sciences at the PennState Cancer Institute, told Live Science.

Changes in sexual behavior, such as a decrease in condom usage and an increase in risky sexual behavior due to opioid use, are likely also playing a role, experts told Live Science.

Related: New 'concerning' strain of drug-resistant gonorrhea found in U.S. for 1st time

Why are STI rates increasing?

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracks the national rate of gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis infections. Rates of these bacterial STIs were already rising in the six years preceding the pandemic. Over this period, gonorrhea rates increased by an average of roughly 10% each year, chlamydia rates increased by an average 3.6% annually and syphilis rates increased by an average 14% annually.

In 2021, during the pandemic, gonorrhea and chlamydia rates continued to increase, rising by around 2.5% compared to 2020, according to the latest CDC data. Both diseases can make sex painful and lead to infertility, while gonorrhea can also lead to yellow-green discharge from the genitals.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Syphilis case rates surged more sharply in the same time period, to their highest rate in three decades — a 27% uptick compared to 2020. Syphilis can cause genital ulcers and rashes across the hands and feet.

Soaring syphilis infections are particularly concerning as they are tied to rising rates of congenital syphilis, where the bacteria pass through the placenta during pregnancy, potentially causing bone deformities, nerve problems and, in some cases, miscarriage, stillbirth or death of the newborn. Congenital syphilis infection rates roughly tripled from 2017 to 2021, according to the CDC data.

"In the early 2000s, we were near eradicating syphilis here in the U.S., so it's a bit terrifying to see how much syphilis has come back, ripping and roaring through our communities," Dr. Joseph Cherabie, an assistant professor of medicine and medical director at the St. Louis County Sexual Health clinic, told Live Science.

The true picture may be even worse as "cases were underreported," especially amid pandemic-related disruptions that caused widespread closures of sexual health clinics and diverted staff from tracking STIs to monitoring COVID-19, Cherabie said. These disruptions, along with those caused by last year's mpox outbreak, probably increased STI rates because more people were having sex while unknowingly being infected, Cherabie said.

One factor many scientists think is behind the rise in STI rates is the growing opioid epidemic. Use of opioids, including prescribed painkillers and illicit drugs such as heroin and fentanyl, reached new heights amid the pandemic and has been linked to risky sexual behavior that raise the risk of STI spread, such as not using a condom and having many sexual partners, Cherabie said.

In addition, the high levels of opioid use seen in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities may help explain their rising rates of HIV seen in recent years, Cherabie said.

After decreasing for some time, rates of new HIV diagnoses among AI/AN people began rising again between 2018 and 2021, CDC data suggest. This could theoretically be linked to opioid use, since needle sharing can increase people's risk of contracting HIV, which also spreads through sexual contact, Cherabie said. What's more, medications that dramatically reduce the chance of getting HIV, called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), are less readily available in these communities, compared to groups whose HIV rates are declining, he said.

Another driver of surging STI rates is the declining use of condoms, Dr. Jodie Dionne, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham told Live Science.

"Several studies are showing a pretty consistent decrease in condom use," which acts as a physical barrier against the transfer of STIs, Dionne said. One study that surveyed condom use among over 29,000 female U.S. residents ages 15 to 44 found that 3% fewer people reported using a condom during their last instance of vaginal sex between 2017 and 2019, compared to rates reported a decade earlier.

Condoms are particularly falling out of favor among those taking PrEP, Cherabie added. A recent study found that, between 2012 and 2017, rates of condomless sex have increased among men who have sex with men, and other research suggests this shift in behavior may be partially tied to the increased use of PrEP, which guards against HIV but not other STIs.

"We need to make sure these people are aware they can get other STIs apart from HIV, and they need to get tested every three to six months if they are having new sexual partners," Cherabie said.

How can STI rates be reduced?

So what measures can reverse this trend?

One strategy is to increase STI testing. Strengthening efforts to screen for STIs, as well as congenital syphilis, through increased funding could help to reverse rises in infection rates, Cherabie said. Sexual healthcare has been underfunded for decades, he said.

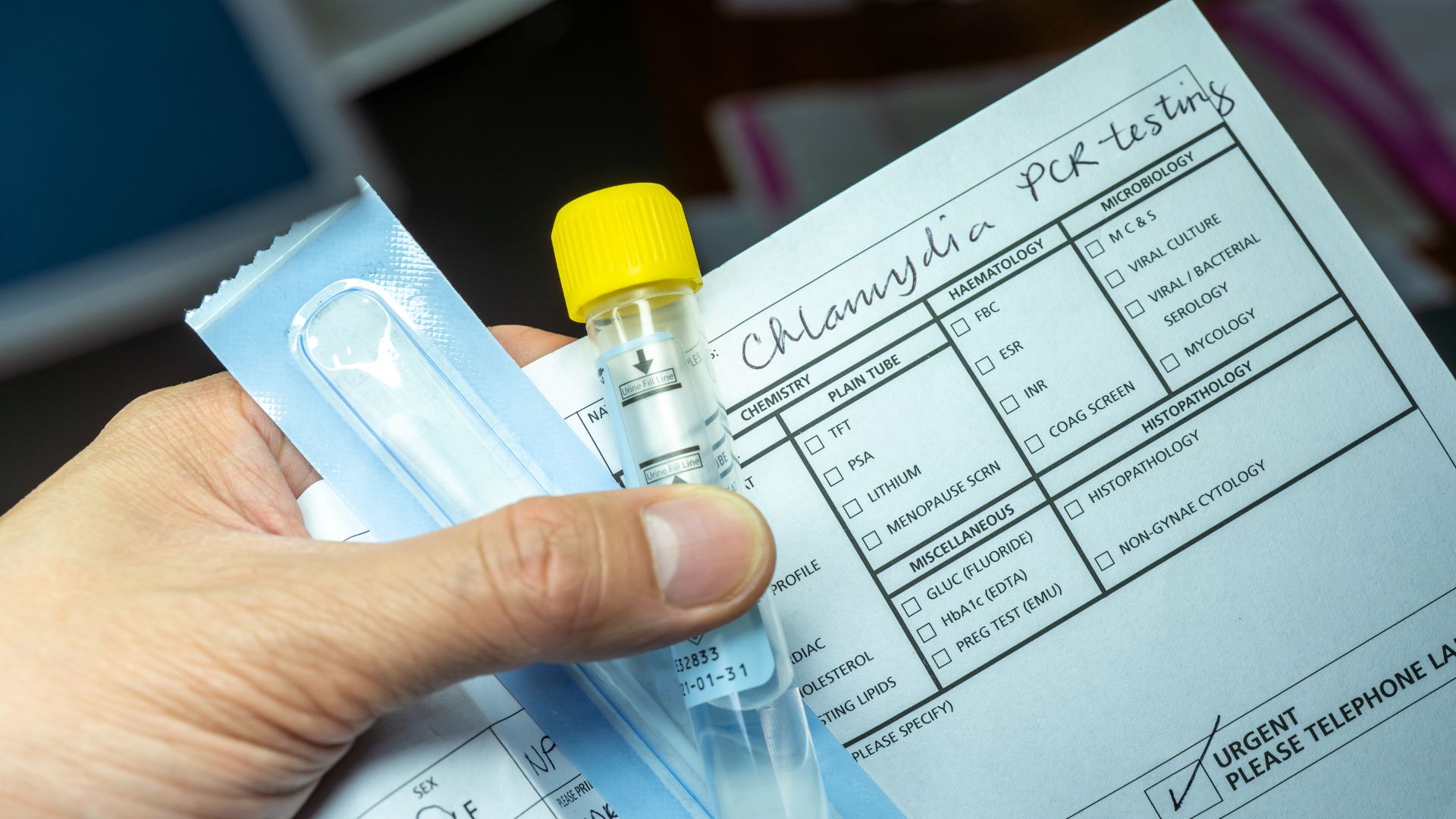

A "terrific opportunity" to boost testing is via at-home test kits, Dionne said. "One useful thing we learned during the COVID-19 pandemic is how readily people can perform self-swabbing at home when high quality test kits are made available. We can and should expand this self-testing capacity to include chlamydia and gonorrhea self-testing outside of the clinic," Dionne said. Self-testing for syphilis may be trickier as it requires a blood test, she noted.

Ongoing trials are exploring the feasibility of government-funded test kits for chlamydia, gonorrhea and HIV, which can each cost from around $80 to $300. "In trials in Jefferson County, Alabama, we've seen that many people ordering free STI self-testing kits have rarely or never been screened for STIs in the past," Dionne said. At-home tests could be a worthwhile investment if they reach historically stigmatized groups who face a disproportionate risk of STIs, she said.

Using less stigmatizing language to inform vulnerable groups about STIs could also encourage people to get tested, which could drive down infection rates, Cherabie said. Whether that will actually impact outcomes, however, is unclear — researchers have a "very limited understanding" as to whether changing levels of stigmatization contributed to the recent rise in STI rates, Dionne said.

Scientists initially wondered whether STIs rates are increasing due to emerging antibiotic resistance among pathogens. But so far, that doesn't seem to be the case, Dionne said. Nevertheless, antimicrobial-resistant strains are "something we want to keep an eye on, because with increasing antimicrobial resistance, we are less likely to get rid of the infection," Cherabie said.

As the burden of STIs grows larger, the CDC announced funding for a new STI research consortium aimed at reversing current trends on Feb. 27, 2023. This could be a first step in slowing or reversing the rise in STI rates.

Carissa Wong is a freelance reporter who holds a PhD in cancer immunology from Cardiff University, in collaboration with the University of Bristol. She was formerly a staff writer at New Scientist magazine covering health, environment, technology, nature and ancient life, and has also written for MailOnline.