Why did Rome fall?

Who says it did?

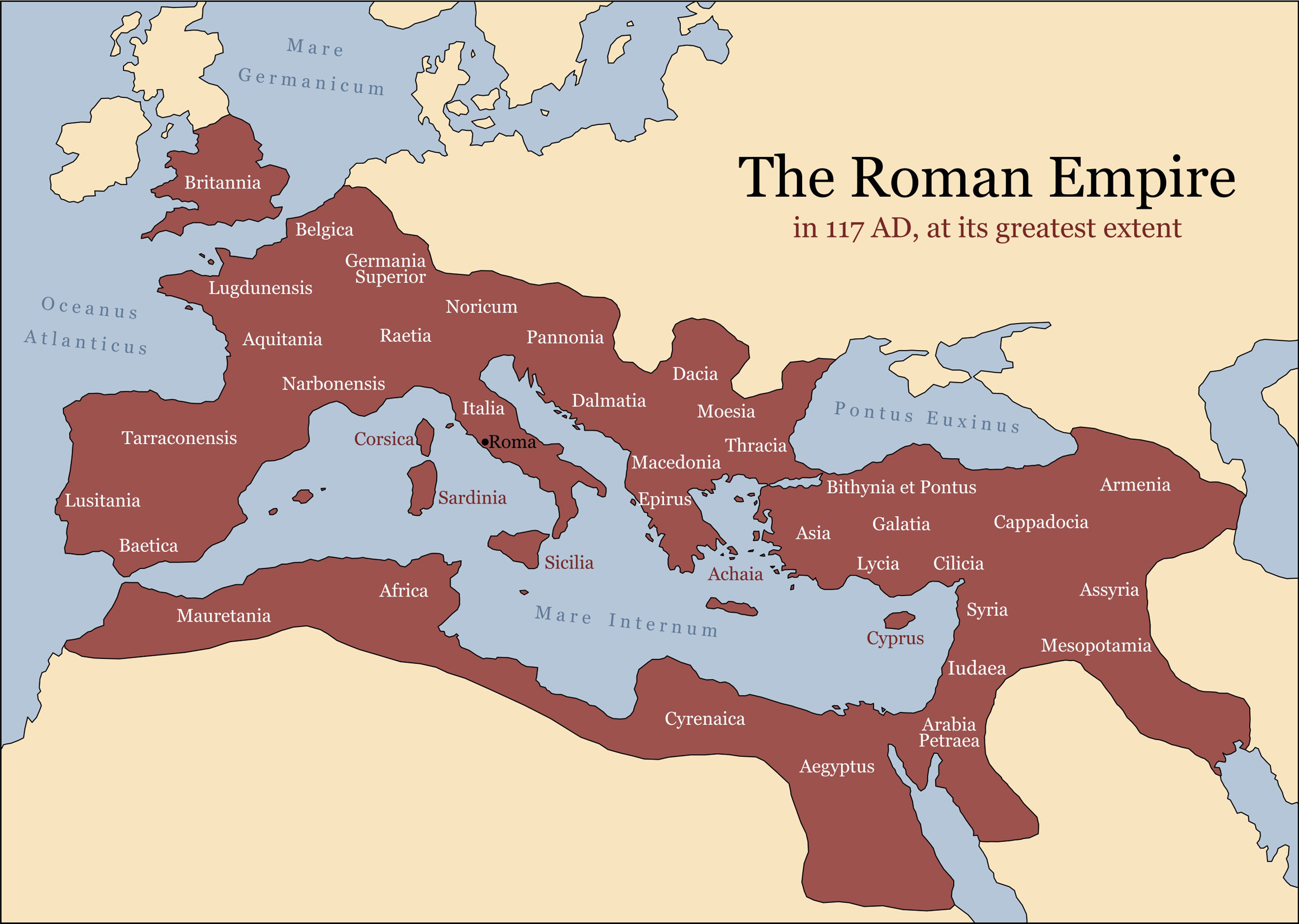

When the Roman Empire was at its height, the emperor's reach stretched from the rain-sodden hills of northern England to the parched deserts of Saudi Arabia. But when did it start to go wrong? Why did Rome fall?

The answer, it turns out, is not straightforward. Some argue the sacking of Rome in A.D. 410 by the Visigoths is as good a marker as any for the end, while others say it wasn't until the Middle Ages that the empire's tenure was finally concluded. Largely speaking, it depends on which ancient Rome we're talking about. In A.D. 395 the Roman Empire was split in two, ever after separately administered as the Western Roman Empire with Rome as its capital and the Byzantine, Eastern Roman Empire with Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) as its capital, according to HistoryHit, an online-only history channel.

"We tend to think of the Byzantines as this separate people and state from the Romans, but they called themselves "Romanoi" and saw themselves as citizens of a Roman government," said Kristina Sessa, associate professor of history at The Ohio State University.

The fates of these two jurisdictions inevitably diverged. The Western Roman Empire fragmented as various provinces suffered economic and political disrepair within decades of the split. The Eastern Roman Empire was meanwhile comparatively prosperous for several centuries. "You need to distinguish these different regional trajectories," Sessa told Live Science.

Related: Deformed 'alien' skulls offer clues about life during the Roman Empire's collapse

The West crumbled because of a creeping and steady loss of centralized control, sometimes due to incursions by non-Roman tribes and occasionally instigated by traitors from within the Roman establishment. It's hard to mark the precise moment when Rome lost control over a given territory, because unlike the decolonization of imperial empires in the 20th century, it was rare to make or sign documents and declarations of independence. There were however, landmark battles — between A.D. 460 and A.D. 480, the Visigoths had managed to take substantial parts of what is now France. But still, the decline of Western Rome was a fairly gradual, nebulous process wherein colonies, one by one, were no longer realistically under the sway of an emperor in Rome. Instead, autonomous local leaders were increasingly in charge.

"In some cases, these were Roman usurpers," who used coups to take power, said Sessa. In other cases, these autonomous regions were headed by so-called barbarian regimes. But the barbarians — such as the Franks, Saxons and Vandals — weren't simply raiders from foreign lands chipping away at a weaker Rome. That's selling those groups short. "That map with all the arrows of invaders coming into the empire from beyond and taking it over, which commonly appears in textbooks, is flat out wrong," said Sessa. Many of the barbarians were coalitions of soldiers that had been working with and for the Roman Empires for several generations.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They had been living and working inside the Roman Empire, on behalf of the Roman Empire, for decades if not centuries," said Sessa. That gave the barbarians the opportunity to learn Roman tactics and expertise, which they then applied against the empire, resulting in a series of withering military defeats for the Romans. "The Roman frontier wasn't a border in the modern sense of the nation state. It was simply a region of diminishing Roman influence where people moved freely around," she said.

In that context, it's easy to see how the frontier could shrink over time. "Without a central state, taxes were no longer regularly collected in most areas of the West, which obviously impacted the military," explained Sessa. Dwindling tax revenue made it increasingly tough for Rome to muster enough legions to reclaim lands the barbarians had taken.

While the Roman Empire in Western Europe was going to hell in a handbasket, the Eastern Romans carried on. "The East, by comparison, remained consolidated and focused around the city of Constantinople," said Sessa.

Its demise, however, was very much at the hands of an outside invading force.

"It was over the course of the seventh and eighth centuries that the Eastern Empire began to undergo a similar political fragmentation, though in this case we are talking about external armies and regimes; the Persians, the Slavs and the Arabs," she added. It wasn't until 1453, when the Ottomans sacked Constantinople, that we can truly say the Roman Empire ended.

Originally published on Live Science.

Benjamin is a freelance science journalist with nearly a decade of experience, based in Australia. His writing has featured in Live Science, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, Associated Press, USA Today, Wired, Engadget, Chemical & Engineering News, among others. Benjamin has a bachelor's degree in biology from Imperial College, London, and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University along with an advanced certificate in science, health and environmental reporting.