Why don't hurricanes form at the equator?

Here's why hurricanes, also known as tropical cyclones and typhoons, don't form at the equator and why it would be rare for them to cross it.

The fierce winds of a hurricane are known as tropical cyclones in some parts of the world, so you might expect them to sweep across the entire tropics. But there's one area of the tropics where hurricanes almost never form: the equator.

Historical maps of the locations of tropical cyclones (also known as typhoons and hurricanes, depending on the location) would reveal that "it is extremely rare for them to form within a few degrees of the equator," Gary Barnes, a meteorologist who's now retired from the University of Hawaii, told Live Science. (One degree of latitude covers about 69 miles, or 111 kilometers.)

But why aren't there hurricanes at the equator?

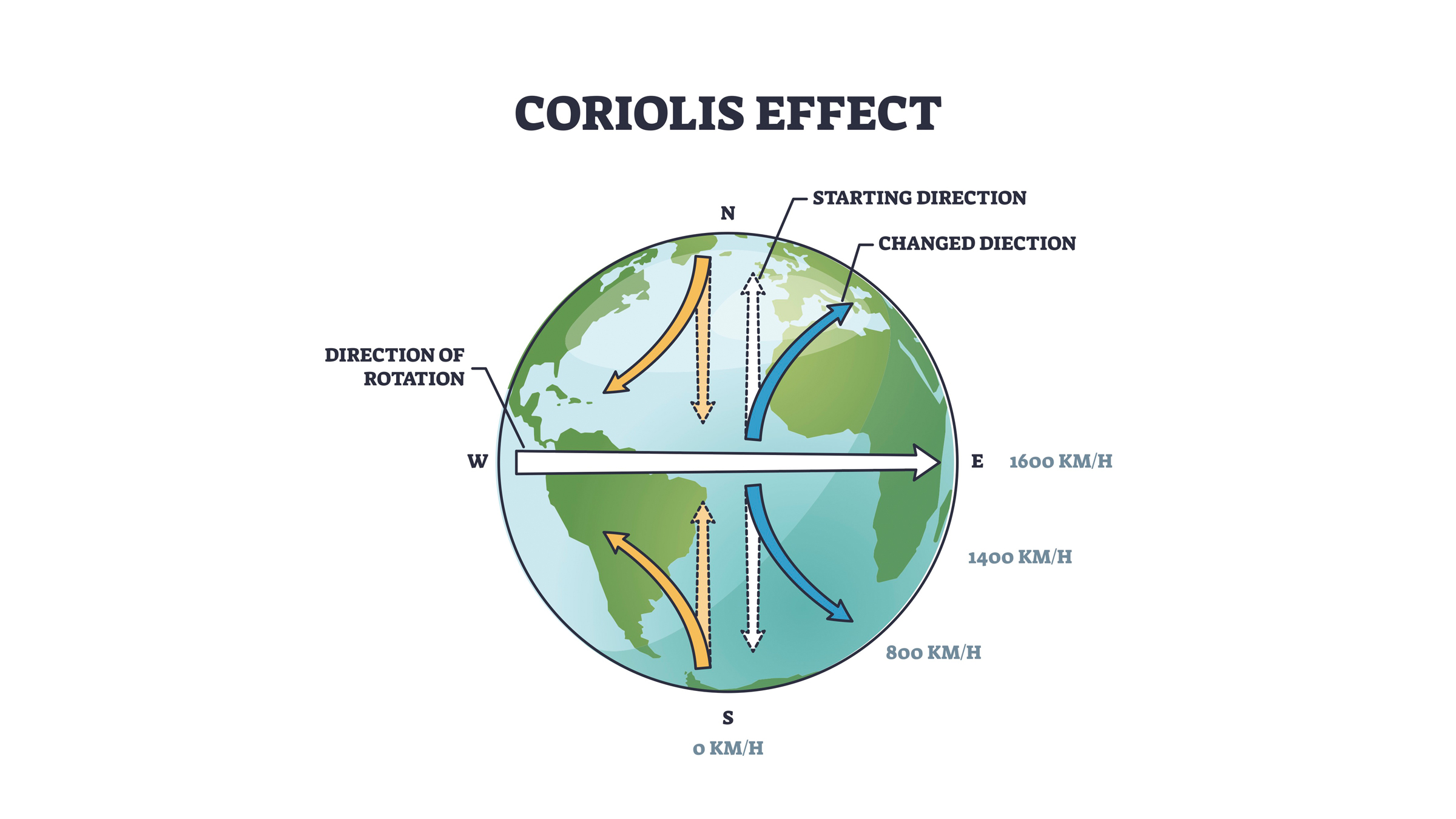

The reason is linked to why tropical cyclones rotate, which is due to Earth's spin. At the equator, even when the air is calm, the planet and the atmosphere above it are actually moving at over 1,000 mph (1,600 km/h), Barnes said. This movement follows Earth's direction of spin from west to east.

Related: How many satellites orbit Earth?

Earth's circumference is largest at the equator. This means anything standing on the equator is moving faster eastward than anything lying away from the equator — anything on the equator is traveling a greater distance than anything north or south on Earth's surface in the same amount of time.

If air moves north from the equator, it will also still flow quickly eastward compared with its new surroundings. This means air traveling north from the equator will appear to veer right. In contrast, air flowing south from the equator will appear to stray left.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This phenomenon, known as the Coriolis effect, helps control the direction in which tropical cyclones spin. In the Northern Hemisphere, rightward-turning air will create a counterclockwise spinning motion, and the opposite will occur in the Southern Hemisphere.

"Hurricanes collect rotation from the environment around them," Paul Roundy, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Albany in New York, told Live Science.

This apparent turning of the wind "is very weak near the equator but becomes much stronger as latitude increases," Barnes said. This is why tropical cyclones only rarely form near the equator — higher latitudes have faster-spinning winds to help drive tropical cyclone growth.

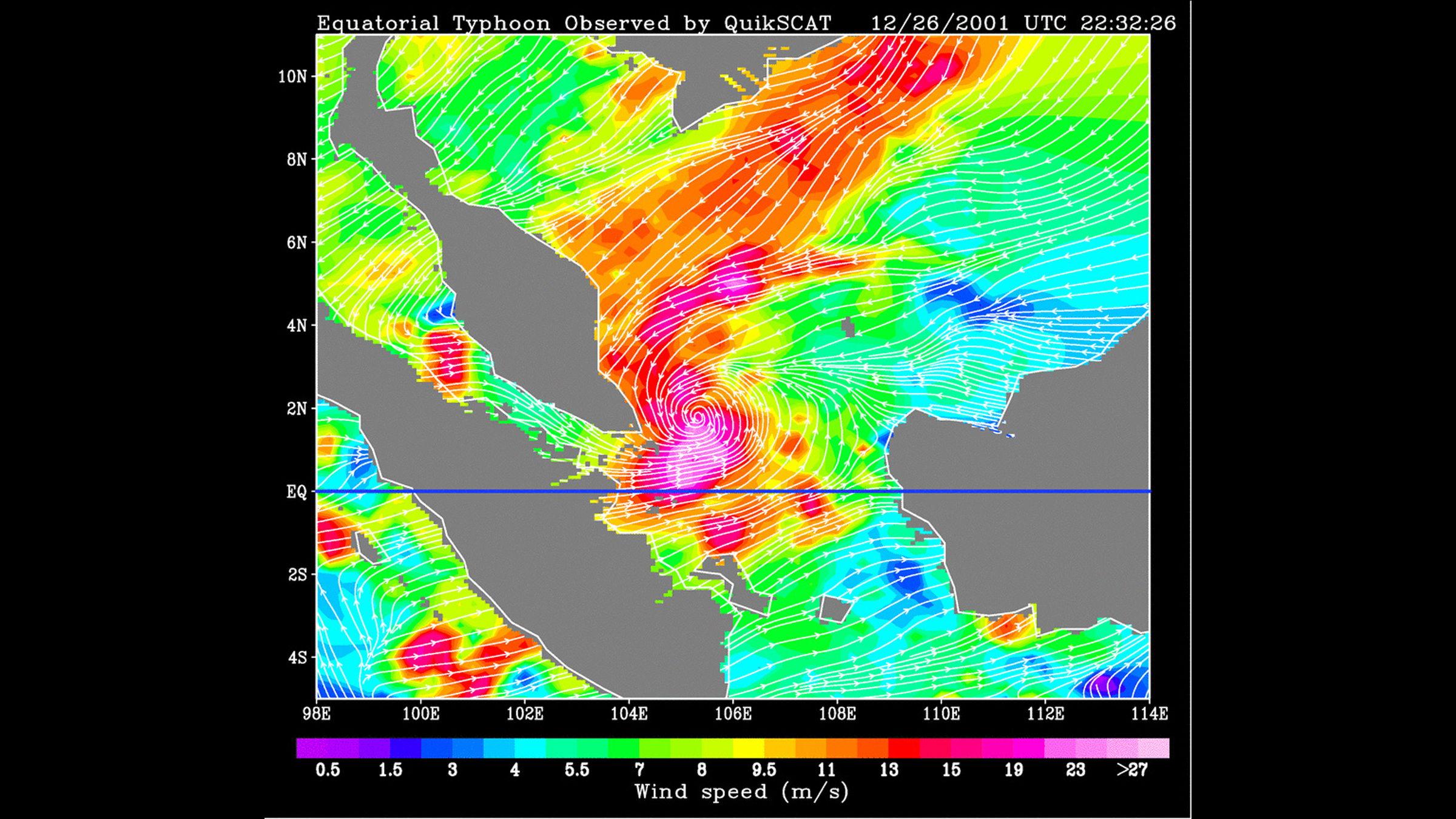

Still, "there are odd exceptions," Barnes noted. For instance, in 2001 the South China Sea, Tropical Cyclone Vamei "intensified within 2 degrees of the equator, but the nascent circulation actually formed earlier, farther away from the equator," he said. Scientists think winds interacting with island terrain in the Indonesian archipelago may have generated the rotation that gave rise to Vamei, he said.

If a tropical cyclone were to cross the equator, "it would begin ingesting air rotating in the opposite direction," Roundy said. Barnes noted that this would likely drive the storm to weaken and collapse.

However, "it's conceivable that a storm could cross the equator some small distance, since the opposing rotation remains fairly small close to the equator," Roundy said. "It is probably not possible for a tropical cyclone to cross several degrees of latitude into the opposite hemisphere."

Climate change "does not significantly affect the rotation of the Earth, so it won't directly impact the chances of a hurricane crossing the equator," Roundy noted. "However, if rare storms at low latitude were able to achieve higher intensities, if they happened to move toward the equatorial region, they might better maintain there. Climate change might increase the strength of the strongest storms."