Why do hummingbirds 'hum'?

Answering this question took multiple high-speed cameras and thousands of microphones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Colorful hummingbirds get their name from the hum generated by their fast-moving wings as they hover; these tiny aerodynamic marvels have the fastest wingbeat of all birds, clocking in at around 70 strokes per second (more than 4,000 per minute).

But how exactly do their wings produce a humming noise? Researchers recently took a closer look at hummingbirds as the birds hovered and flew, to better understand what generated their signature sound.

The scientists created the first-ever 3D acoustic model of flying hummingbirds, combining video and audio recordings of the birds in motion with measurements of the forces generated by hummingbird wings as they oscillated. The team traced the humming sound to the upstroke of hummingbird wingbeats, which provided the birds with an extra boost of lift — unlike the upstrokes in the wingbeats of other birds.

Related: How high can birds fly?

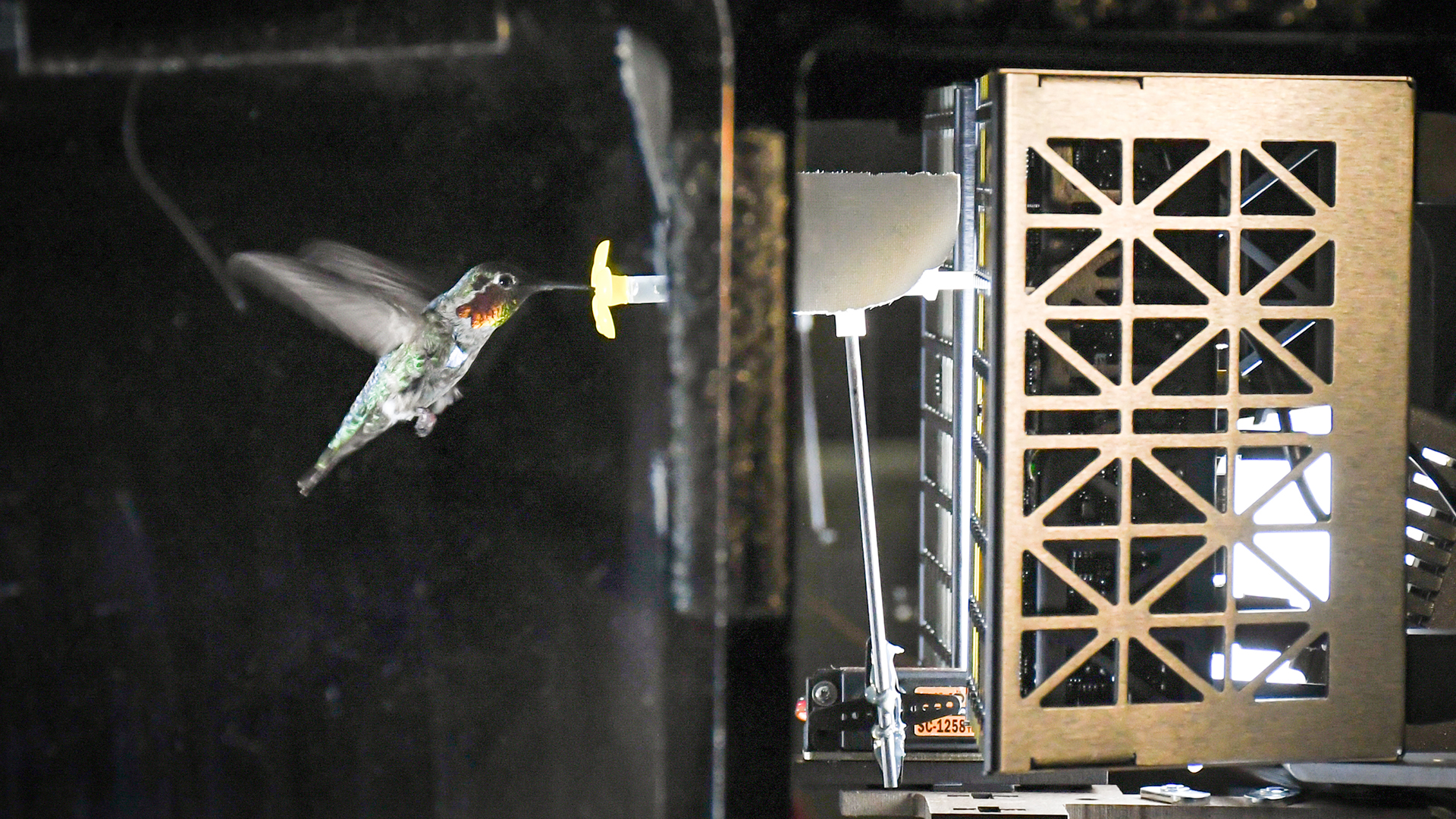

To capture all the elements of hummingbird flight, the researchers used sensitive pressure plates that measured the force of wingbeats, a dozen high-speed cameras, 2,176 microphones and six obliging Anna's hummingbirds (Calypte anna) that were each caught, filmed and released on the same day, according to a new study published March 16 in the journal eLife.

The captured birds were brought to a specially constructed flight enclosure at Stanford University. As the free-flying hummingbirds fluttered around the enclosure and sipped nectar from fake flowers, they were filmed by high-speed cameras that were linked to microphone arrays "to make the sound visible," said Rick Scholte, a researcher and CEO for Sorama, an offshoot of Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands and the company that created this acoustic visualization system.

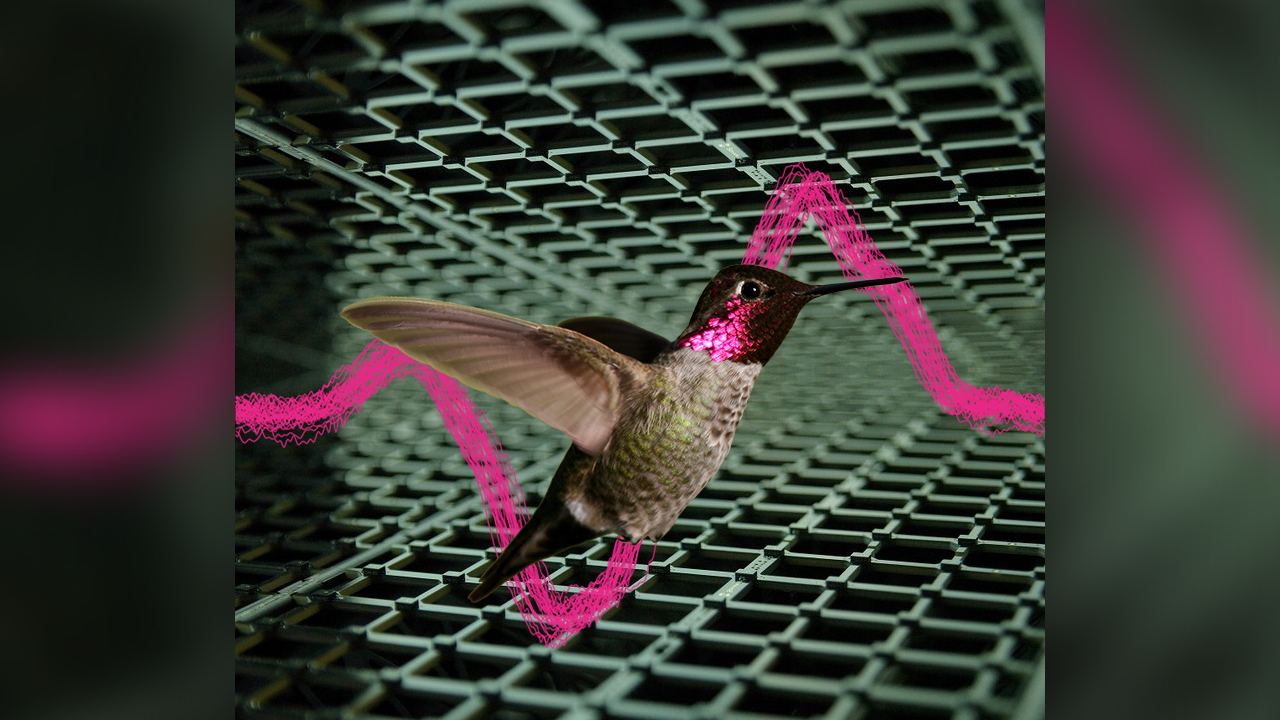

"Together they work a bit like a thermal camera that allows you to show a thermal image," said Scholte, co-author of a new study published March 16 in the journal eLife. "We make the sound visible in a 'heat map', which enables us to see the 3D sound field in detail, he said in a statement. This enabled the scientists to create a frame-by-frame map synching audio data to wing motion.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another piece of the puzzle was the amount of aerodynamic force generated by the hummingbirds' wings during upstrokes and downstrokes, which the scientists measured using pressure plates, said lead study author Ben Hightower, a researcher who conducted these experiments when he was a doctoral candidate at Stanford's School of Engineering. Gravity is constantly pulling the hummingbirds down, but the force the birds generate from wing flaps to offset gravity's pull varies a little with every beat, Hightower explained.

"During the downstroke they're creating more lift, and then during the upstroke they're creating a little bit less lift," he said.

In most flying birds, the "whoosh" that you hear is the sound of their downstroke — the only wingbeat to generate lift. By comparison, hummingbird wings, which trace a "U" shape in the air as they flap, produce lift on both the downstroke and upstroke, the study authors found. At the speed that hummingbird wings move, these actions and air pressure differences during wingbeats account for the hummingbirds' humming sound. Variability in the way air moves over feathers and the wing's overall shape add overtones and nuance to the sound. This make the hum sound pleasant to humans — unlike the more irritating whine of a mosquito or the buzzing of a fly, according to Scholte.

"A hummingbird wing is similar to a beautifully tuned instrument," Scholte said.

But how does the hum of fast-moving wings sound to a hummingbird? In some species of hummingbirds, males generate high-pitched mating calls by vibrating their tail feathers, the study authors wrote. Might the hum of hummingbird wings also serve as a form of communication? It's unknown how well the birds can hear the sound of humming while in flight, but it's possible that this might play a role in how the birds interact with each other, Hightower said.

"Hummingbirds are very territorial; if you've ever seen them around a feeder, they will fend off other hummingbirds. It'd be interesting to see if hummingbirds can use the hum to detect other hummingbirds in the area," he said.

Hummingbirds also dine on fruit flies — so, can fruit flies hear those humming wings, and can they thereby tell when a bird is nearby and about to strike?

"Those are two questions that stick out to me as interesting areas to look into," Hightower said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus