Why is there still no male birth control pill?

Researchers have spent half a century investigating contraceptives for men, but how close are we to getting a male birth control pill?

With no male birth control pill currently on the market, contraceptive options for men are limited. Instead, birth control generally falls to women, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reporting that of all the sexually active women using contraceptives in the United States, just 8.6% rely on the man wearing a condom.

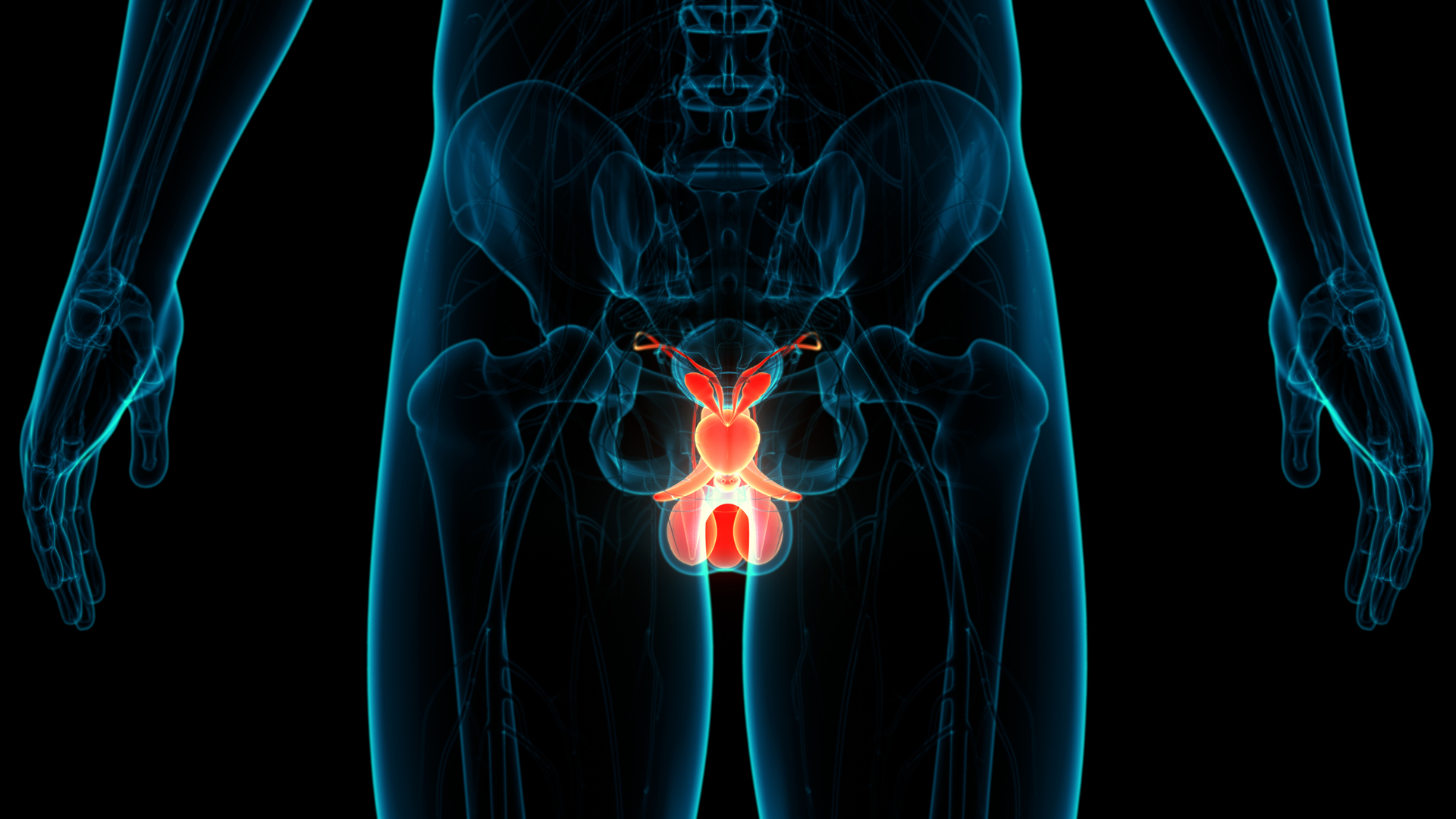

Aside from a condom, the other option for male birth control is a vasectomy — a procedure that blocks the tubes carrying sperm from a man’s testicles to the penis. This can be costly to have and even more expensive to reverse. Planned Parenthood reports a vasectomy can cost up to $1,000, depending on your personal circumstances and healthcare plan, while the Mayo Clinic notes that the procedure also comes with risks and side effects. These can include bruising, swelling and blood in the semen.

But scientists are getting closer to developing a male birth control pill that is safer, effective and doesn't impact fertility later down the line. The candidate closest to sale is a hormonal contraceptive pill that works by stopping the testicles from making testosterone, which affects sperm production.

Here, we look at how the male birth control pill works, what barriers stand in its way to market, and whether there are any other contraceptives that could be developed sooner.

How does the male birth control pill work?

Just like the female hormonal contraceptive pill, the male birth control pill works by blocking signals from the brain to the reproductive system. Most researchers are targeting one signal in particular, according to a 2021 review published in Fertility and Sterility: the brain's message to the testicles to produce the hormone testosterone.

Testosterone has a range of responsibilities in the body. It maintains a man's libido, stimulates the growth of new bones and muscles, and supports other organs in the reproductive system like the prostate. But it also plays a key role in sperm production.

High levels of testosterone in the testicles stimulate the testes to make viable sperm, said Dr. Stephanie Page, a professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine and a lead researcher on studies into contraceptives for men, including a potential male birth control pill.

"We can give men testosterone [via a pill] so that the brain senses that there's plenty of testosterone in the body and the man stops making testosterone within the testicle," Page told Live Science. "Without high concentrations of testosterone in the testicle itself the sperm don't mature."

Dr. Stephanie Page completed her undergraduate degree at Stanford University before moving to Seattle where she received her MD and PhD in immunology from the University of Washington. She completed her residency in medicine at the University of Washington in 2002 and her fellowship training in Endocrinology and Metabolism in 2006. Page serves as the section head for the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Her research focuses on male reproduction and the development of novel male hormonal contraceptives.

As with other hormones, the brain has to monitor the level of testosterone in the bloodstream and send out signals to start or stop making more of the hormone as needed. Natural testosterone circulates via blood around the body, but the hormone is also made in high quantities within the testicle to get a direct line to sperm production. Testicular testosterone can be as much as 1,000 times more concentrated than that of the blood, Page said.

When testosterone is given orally, the hormone travels through the bloodstream to other spots in the body and is recognized by the brain in the same way as natural testosterone. In the male birth control pill, this circulating testosterone is at the right concentration to signal to the brain to stop making the hormone elsewhere, including in the testes. But very little, if any, of the testosterone from the pill can get into the testicles, Page said. With the body not making testosterone and none reaching the testes, mature sperm are unable to develop.

However, one of the problems with taking testosterone orally is that the body breaks it down quickly, meaning men would have to take a pill two or three times a day to effectively suppress sperm production, Page said.

This led Page and her colleagues to investigate a different compound called dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU), which can also block the production of testosterone in the testicles. DMAU stays in the body for at least 24 hours, making it similar to the daily female pill.

Male birth control pill: What do we know so far?

A 2018 study of the male birth control method DMAU in 100 men found that the pill markedly reduced levels of testosterone. DMAU is currently in phase one clinical trials, which involve studies into different dosages, any side effects and close monitoring of sperm counts, said Page.

Only after it has completed basic safety tests can its effectiveness be tested in a small number of couples.

In addition to male birth control pills, Page and colleagues are working on a non-oral form of contraception — a hormonal gel. This gel is applied to men's shoulders daily and delivers testosterone into the body and bloodstream, blocking the signals to the testicles. The gel is already in phase two trials and has shown promise among its first 100 couples, Page said.

Though they have yet to publish results, Page said that their research into the gel contraceptive shows "for sure that it's very effective" in reducing sperm count.

In most cases, men's sperm counts dropped to less than 1 million per milliliter of ejaculate, compared with 15 to 200 million per milliliter found in a healthy, fertile man. Anything under 15 million is considered a low sperm count, according to the Mayo Clinic, and can make it more difficult to conceive.

"That's at least as good as the female birth control pill, and probably better," Page said.

Male birth control pill: What do we still not know?

Some men worry about potential side effects with a hormonal contraceptive. But Dr. Brian Nguyen, assistant professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology at Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, found that most men in the clinical trials of the hormonal gel are willing to accept some potential side effects in exchange for the peace of mind the contraceptive would offer.

"There could be some changes to mood, libido, skin problems like acne, and weight gain," Nguyen told Live Science, who worked together with Page on a 2022 study into men’s openness to using DMAU, published in the Contraception journal.

Similar side effects have been noted in some women taking hormonal contraceptives, including a small percentage of people with libido changes, according to a 2012 review published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

"But no matter what birth control method you use, there will always be some kind of untoward side effect, because you're applying something that inevitably changes some function of the body," Nguyen said.

For him, the more important question is which person in a relationship is more willing to accept the side effects of contraception. Currently, that role often defaults to women, but male birth control pills will provide couples in heterosexual relationships with more choice.

There are also non-hormonal options being tested, such as a penile injection that temporarily blocks the tubes by which sperm travel out of the testicles in ejaculate — similar to a vasectomy.

Other researchers are developing implants that could release contraceptive drugs into the body over a longer period of time. But Nguyen believes the hormonal options are the most promising because they have proven reversibility and don't touch the "machinery" of sperm production.

When it comes to long-term effects of hormonal male birth control, early studies show that sperm counts return to normal levels within eight to 12 weeks, Page said. But more research is needed to say confidently that fertility isn't impacted once a man stops using the contraceptive.

When could we expect a male birth control pill?

One barrier to putting new male contraceptives on the market is unclear regulatory standards from agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Page said.

"We still don't know how many people need to be studied and for how long, before a male birth control pill could be approved."

Page said this makes investors hesitant to fund studies. Nguyen agreed that this is another barrier to the development of the pill for men.

"I think that what we've learned from the COVID vaccine studies is that if there's enough investment in the industry, we [scientists] can move very quickly," Nguyen said.

With the pill in phase one trials and the gel in phase two, both Page and Nguyen believe we're much closer to seeing the non-oral option available for use. Other studies, such as the non-hormonal injection or implant, still need to publish human trial results that will meet FDA standards.

"I think the soonest we could get the gel to the market is probably about seven years and that would be if things go really well," Page said. Nguyen is cautiously optimistic that the next 10 years could see both the gel and pill options on sale. The 2030s, then, could be the decade of new male birth control options.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Amy Arthur is a U.K.-based journalist with a particular interest in health, medicine and wellbeing. Since graduating with a bachelor of arts degree in 2018, she's enjoyed reporting on all kinds of science and new technology; from space disasters to bumblebees, archaeological discoveries to cutting-edge cancer research. In 2020 she won a British Society of Magazine Editors' Talent Award for her role as editorial assistant with BBC Science Focus magazine. She is now a freelance journalist, with bylines in BBC Sky at Night, BBC Wildlife and Popular Science, and is also working on her first non-fiction book.

Man gets sperm-making stem cell transplant in first-of-its-kind procedure

'Love hormone' oxytocin can pause pregnancy, animal study finds