Why haven't we cloned a human yet?

Is it for ethical reasons or are there technological barriers?

In 1996, Dolly the sheep made headlines around the world after becoming the first mammal to be successfully cloned from an adult cell. Many commentators thought this would catalyze a golden age of cloning, with numerous voices speculating that the first human clone must surely be just a few years away.

Some people suggested that human clones could play a role in eradicating genetic diseases, while others considered that the cloning process could, eventually, eliminate birth defects (despite research by a group of French scientists in 1999 finding that cloning may actually increase the risk of birth defects).

There have been various claims — all unfounded, it is important to add — of successful human cloning progams since the success of Dolly. In 2002, Brigitte Boisselier, a French chemist and devout supporter of Raëlism — a UFO religion based on the idea that aliens created humanity — claimed that she and a team of scientists had successfully delivered the first cloned human, whom she named Eve.

However, Boisselier was unwilling — or indeed unable — to provide any evidence, and so it is widely believed to be a hoax.

So why, almost 30 years on from Dolly, haven't humans been cloned yet? Is it primarily for ethical reasons, are there technological barriers, or is it simply not worth doing?

Related: What are the alternatives to animal testing?

"Cloning" is a broad term, given it can be used to describe a range of processes and approaches, but the aim is always to produce "genetically identical copies of a biological entity," according to the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Any attempted human cloning would most likely utilize "reproductive cloning" techniques — an approach in which a "mature somatic cell," most probably a skin cell, would be used, according to NHGRI. The DNA extracted from this cell would be placed into the egg cell of a donor that has "had its own DNA-containing nucleus removed."

The egg would then begin to develop in a test tube before being "implanted into the womb of an adult female," according to NHGRI.

However, while scientists have cloned many mammals, including cattle, goats, rabbits and cats, humans have not made the list.

"I think there is no good reason to make [human] clones," Hank Greely, a professor of law and genetics at Stanford University who specializes in ethical, legal and social issues arising from advances in the biosciences, told Live Science in an email.

"Human cloning is a particularly dramatic action, and was one of the topics that helped launch American bioethics," Greely added.

The ethical concerns around human cloning are many and varied. According to Britannica, the potential issues encompass "psychological, social and physiological risks." These include the idea that cloning could lead to a "very high likelihood" of loss of life, as well as concerns around cloning being used by supporters of eugenics. Furthermore, according to Britannica, cloning could be deemed to violate "principles of human dignity, freedom and equality."

In addition, the cloning of mammals has historically resulted in extremely high rates of death and developmental abnormalities in the clones, Live Science previously reported.

Another core issue with human cloning is that, rather than creating a carbon copy of the original person, it would produce an individual with their own thoughts and opinions.

"We've all known clones — identical twins are clones of each other — and thus we all know that clones aren't the same person," Greely explained.

A human clone, Greely continued, would only have the same genetic makeup as someone else — they would not share other things such as personality, morals or sense of humor: these would be unique to both parties.

People are, as we well know, far more than simply a product of their DNA. While it is possible to reproduce genetic material, it is not possible to exactly replicate living environments, create an identical upbringing, or have two people encounter the same life experiences.

Would cloning humans have any benefits?

So, if scientists were to clone a human, would there be any benefits, scientific or otherwise?

"There are none that we should be willing to consider," Greely said, emphasizing that the ethical concerns would be impossible to overlook.

However, if moral considerations were removed entirely from the equation, then "one theoretical benefit would be to create genetically identical humans for research purposes," Greely said, though he was keen to reaffirm his view that this should be thought of as "an ethical non-starter."

Greely also stated that, regardless of his own personal opinion, some of the potential benefits associated with cloning humans have, to a certain degree, been made redundant by other scientific developments.

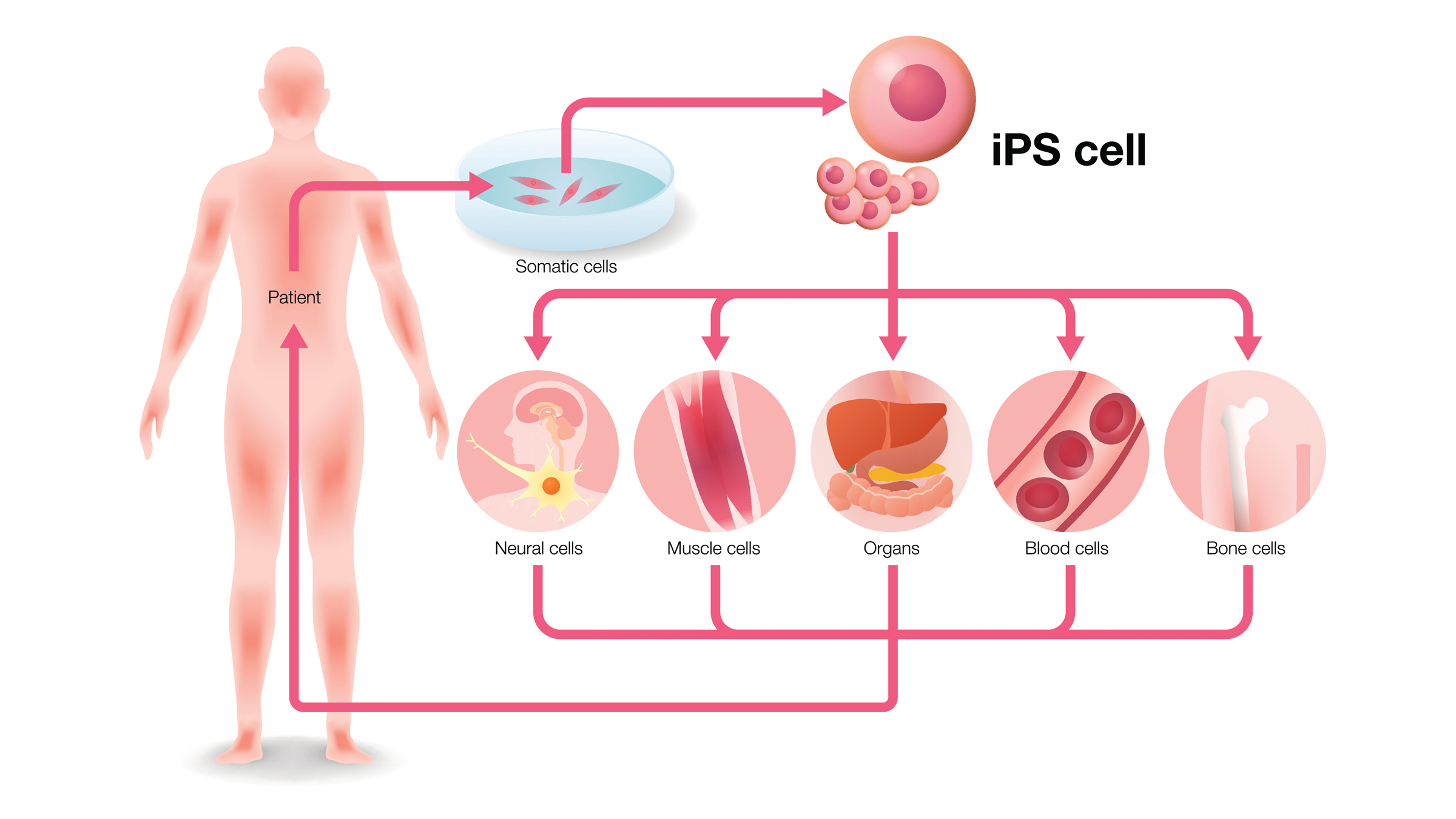

"The idea of using cloned embryos for purposes other than making babies, for example producing human embryonic stem cells identical to a donor's cells, was widely discussed in the early 2000s," he said, but this line of research became irrelevant — and has subsequently not been expanded upon — post-2006, the year so-called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were discovered. These are "adult" cells that have been reprogrammed to resemble cells in early development.

Shinya Yamanaka, a Japanese stem cell researcher and 2012 Nobel Prize winner, made the discovery when he "worked out how to return adult mouse cells to an embryonic-like state using just four genetic factors," according to an article in Nature. The following year, Yamanaka, alongside renowned American biologist James Thompson, managed to do the same with human cells.

When iPSCs are "reprogrammed back into an embryonic-like pluripotent state," they enable the "development of an unlimited source of any type of human cell needed for therapeutic purposes," according to the Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Therefore, instead of using embryos, "we can effectively do the same thing with skin cells," Greely said.

This development in iPSC technology essentially rendered the concept of using cloned embryos both unnecessary and scientifically inferior.

Related: What is the most genetically diverse species?

Nowadays, iPSCs can be used for research in disease modeling, medicinal drug discovery and regenerative medicine, according to a 2015 paper published in the journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.

Additionally, Greely also suggested that human cloning may simply no longer be a "sexy" area of scientific study, which could also explain why it has seen very little development in recent years.

He pointed out that human germline genome editing is now a more interesting topic in the public's mind, with many curious about the concept of creating "super babies," for example. Germline editing, or germline engineering, is a process, or series of processes, that create permanent changes to an individual’s genome. These alterations, when introduced effectively, become heritable, meaning they will be handed down from parent to child.

Such editing is controversial and yet to be fully understood. In 2018, the Council of Europe Committee on Bioethics, which represents 47 European states, released a statement saying that "ethics and human rights must guide any use of genome editing technologies in human beings," adding that "the application of genome editing technologies to human embryos raises many ethical, social and safety issues, particularly from any modification of the human genome which could be passed on to future generations."

However, the council also noted that there is "strong support" for using such engineering and editing technologies to better understand "the causes of diseases and their future treatment," noting that they offer "considerable potential for research in this field and to improve human health."

George Church, a geneticist and molecular engineer at Harvard University, supports Greely's assertion that germline editing is likely to garner more scientific interest in the future, especially when compared with "conventional" cloning.

"Cloning-based germline editing is typically more precise, can involve more genes, and has more efficient delivery to all cells than somatic genome editing," he told Live Science.

However, Church was keen to urge caution, and admitted that such editing has not yet been mastered.

"Potential drawbacks to address include safety, efficacy and equitable access for all," he concluded.

Originally published on Live Science.

Joe Phelan is a journalist based in London. His work has appeared in VICE, National Geographic, World Soccer and The Blizzard, and has been a guest on Times Radio. He is drawn to the weird, wonderful and under examined, as well as anything related to life in the Arctic Circle. He holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Chester.