Why do wisdom teeth come in so late?

Were these late-blooming teeth ever useful to humans?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

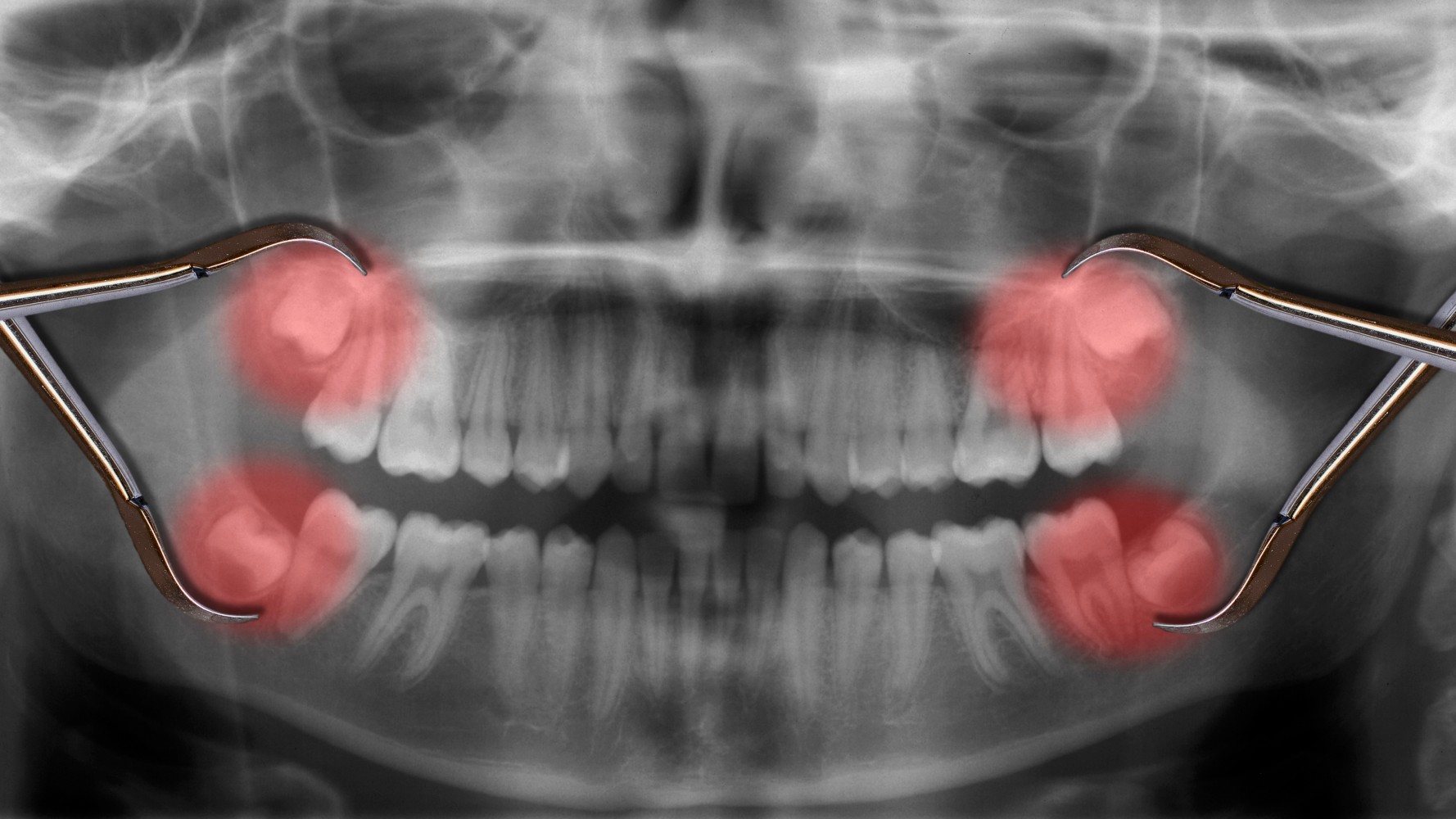

Wisdom-teeth removal is a rite of passage for many people in their late teens and early 20s. But why don't they come in during childhood with the rest of our permanent teeth?

The answer comes down to child development. There's not enough room in a child's jaw for wisdom teeth to come in. But as a kid grows, their jaw grows too, and there's more room for wisdom teeth to emerge, according to an October 2021 study in the journal Science Advances.

However, many modern human jaws don't grow long enough for wisdom teeth to come in without issue, which is why wisdom teeth removal is so common. Again, this is because of child development. Ancient humans ate diets full of hard nuts, uncooked vegetables, gamey meats and other tough foods. Following this diet as a youngster actually makes the jaw grow longer, Julia Boughner, anthropologist at the University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine in Canada, wrote in The Conversation. But as people in industrialized nations have shifted to eating softer foods, we've stopped maxing out our potential of jaw growth.

Related: Does charcoal toothpaste really whiten teeth?

Another reason wisdom teeth come in during young adulthood is that they're not needed until then. When ancient people would grind down or lose their molars to tough food, wisdom teeth — the third set of molars — would take their place. "They're meant as kind of a backup for somebody who may have lost another molar tooth," said Steven Kupferman, an oral surgeon at Cedars Sinai in Los Angeles. But because most people don't lose their molars as young children, wisdom teeth wait until adulthood to arrive. In other words, if you lost your molars or ground them down as a child or teenager, your wisdom teeth are programmed to erupt to fill the gap.

The first set of permanent molars, or teeth in the back of the mouth that are designed to grind food, first come in around 6 years of age, when a child starts losing their baby teeth. Around age 12, the second molars emerge, serving as a backup to the 6-year molars in case they develop cavities, Kupferman told Live Science. Third molars, or wisdom teeth, come in around the ages of 17 to 21.

Nowadays, dentists often remove wisdom teeth because their emergence can cause pain in crowded mouths. Even if a person doesn't have pain, removing wisdom teeth in young adulthood can prevent health issues later in life, such as gum infections. Dentists and oral surgeons generally don't remove wisdom teeth as a preventive measure past age 27, because the risks of complications, such as damage to nearby nerves, increase. However, people may get their wisdom teeth removed past this age, usually due to issues such as pain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most people have 32 teeth, including four wisdom teeth. But some have more or less, and some people may be missing their wisdom teeth altogether, Kupferman said. Others may have a fourth molar, called a paramolar, behind each wisdom tooth. There is almost never enough space for paramolars in the modern human mouth, so they are always removed at the same time as the wisdom teeth.

Not everyone gets their wisdom teeth removed, though. "Even today, when people have teeth pulled for braces purposes, they often will keep their wisdom teeth because there's enough room for them," Kupferman said.

However, keeping your wisdom teeth can lead to issues down the line. Not all wisdom teeth pop through the gums during the late teens and early 20s. But as a person gets older and their gums recede, their wisdom teeth may peek through. In this case, the wisdom teeth come through the gums only partway, so they are prone to cavities and thus must be removed, Kupferman said.

"There are naysayers that [claim] all surgeons are just trying to make money by taking out wisdom teeth, but I think if you know any teenagers and you've seen just a few X-rays, you know that there's good reason to take out third molars," Kupferman said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tyler Santora is a freelance science and health journalist based out of Colorado. They write for publications such as Scientific American, Nature Medicine, Medscape, Undark, Popular Science, Audubon magazine, and many more. Previously, Tyler was the health and science Editor for Fatherly. They graduated from Oberlin College with a bachelor's degree in biology and New York University with a master's in science journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus