Will monkeypox become a pandemic?

It's possible, but many factors lower the risk.

As of Sept. 21, the current monkeypox outbreak has infected 62,532 people across 105 countries. Still, the World Health Organization (WHO) has not yet classified the current caseload as a pandemic.

But could that change? Given its spread, could monkeypox become a pandemic?

The answer to that question depends on the definition of "pandemic." A pandemic is a "worldwide epidemic," in which there are high numbers of cases or outbreaks in many countries, Rachel Roper, a professor of microbiology and immunology at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina, told Live Science in an email.

"I think it's a matter of opinion as to just how many cases you have to have in how many countries," Roper said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines pandemic as "a disease event in which there are more cases of a disease than expected spread over several countries or continents, usually involving person-to-person transmission and affecting a large number of people."

There's always a chance that something, such as the virus's genetic code, could change, but several factors reduce the chances that monkeypox will become a pandemic. Even if it does, monkeypox will not exact anywhere near the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts told Live Science.

Historically, monkeypox has not been terribly contagious, and outbreaks have been small

Monkeypox (sometimes abbreviated as MPXV or MPX) "is much less contagious than COVID," Roper said. Typically the transmission chain of monkeypox was short — one case of MPXV transmitted to about seven people maximum before dying out, so outbreaks have been short lived in the past, Roper said. Monkeypox was first documented to infect humans in 1970, and outbreaks since then, excluding the current pandemic, were "kind of small," she said. In countries where it is endemic, monkeypox is always present in animal hosts and typically spreads between humans only when they catch it from animals and start transmitting it to other people.

But an analysis of monkeypox genomes from the current epidemic, published June 24 in the journal Nature Medicine, suggests that the version of the virus that is currently circulating has been passing from human to human in an uninterrupted transmission chain since 2017. This indicates that the average transmission chain is increasing, Roper said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, for monkeypox, the reproductive number (R0), or the number of people directly infected by each person with the disease, has historically been less than 1, meaning any epidemic would burn out eventually even without active disease control measures (In contrast, the R0 for the currently circulating omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is estimated to be between six and 10, according to The Conversation.) But researchers don't know the R0 for the version of monkeypox currently circulating, according to a June 2022 paper in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

It's hard to say why monkeypox is infecting so many people now, she added. It may be because mutations have made it more transmissible, or it may be because it has entered new populations that as a whole, have different behaviors or risk factors that increase transmission rates, Roper said.

For example, in the African countries where monkeypox is endemic, the virus has not previously been known to spread via men having sex with men, Roper said. But the current outbreak is primarily affecting men who have sex with men and spreading through sexual and other close physical contact, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Monkeypox mutates pretty slowly

Monkeypox is a virus made of DNA, as opposed to being made up of single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA). This matters because DNA replication involves fewer mistakes than copying RNA does, so monkeypox mutates more slowly than counterparts such as SARS-CoV-2 or HIV. This gives monkeypox viruses fewer opportunities to evolve to become more transmissible than RNA viruses would, according to the American Society for Microbiology.

Still, for a poxvirus, monkeypox is developing mutations quickly, according to the June Nature Medicine genome analysis. Compared with strains circulating in 2018 and 2019, the currently circulating virus has 50 mutations, most likely picked up while circulating in humans, according to the paper. That's six to 12 times the number of mutations expected based on the typical mutation rate for poxviruses, the paper authors noted.

Not a lung virus

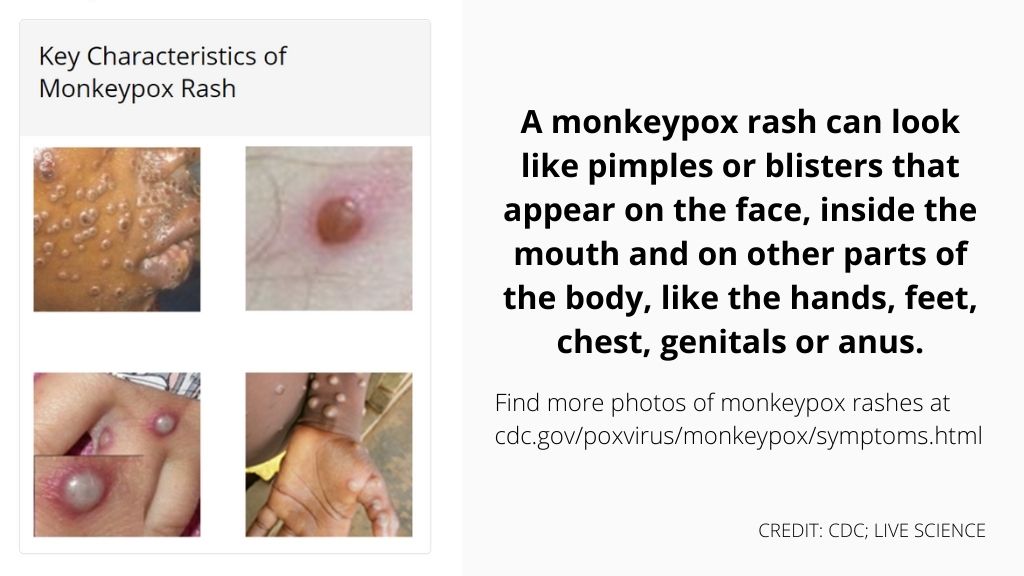

The virus that causes COVID-19 is "majorly respiratory," Roper said. "Its main target organ is the lungs." SARS-CoV-2 spreads when an infected person sneezes, coughs, or even just breathes, Roper said. In contrast, monkeypox is spread primarily by "direct contact with monkeypox rash, scabs, or body fluids from a person with monkeypox," according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The virus can also spread when a person touches objects and surfaces that have been used by someone infected with monkeypox.

"Monkeypox is so inefficient in how it's spread," Rodney Rohde, a professor and chair of clinical laboratory science at Texas State University, told Live Science. "You've got to be really close, skin-to-skin contact, or maybe with fomites like bed linen or clothing. And it actually takes kind of a long time, so several hours of contact, for it to occur, whereas [for] an aerosolized virus, it might be instantaneous — somebody sneezes or coughs in a room and you inhale it, and maybe 8, 10, 12 people get it."

We already have vaccines and treatments for monkeypox

Two vaccines, JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, are approved for use against monkeypox in the U.S., as Live Science previously reported.

While there are no treatments specifically for monkeypox, according to the CDC, antiviral drugs that were developed to fight smallpox, such as tecovirimat (TPOXX), may be recommended for people with weakened immune systems.

Given the existence of vaccines and treatments, combined with other factors, such as the low mortality rate of the monkeypox strain that's currently circulating, it should be possible to slow the rate of infection and limit deaths, Rohde said. The mortality rate for the type of monkeypox circulating in the current epidemic has historically been about 1%, according to the CDC. But the current outbreak may be much less deadly; based on WHO numbers from late September, the fatality rate is 0.04%. While those numbers are still a rough estimate, they do suggest the toll of monkeypox is likely to be much, much lower than that of COVID-19, even if monkeypox does become a pandemic. "It could be deemed a pandemic at some point due to the number of countries that have cases and kind of the linear rise in cases that we're seeing," Rohde said. "But I do not believe it will be the type of global mortality crisis that we saw with COVID."

Originally published on Live Science.

Ashley P. Taylor is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York. As a science writer, she focuses on molecular biology and health, though she enjoys learning about experiments of all kinds. Ashley's work has appeared in Live Science, The New York Times blogs, The Scientist, Yale Medicine and PopularMechanics.com. Ashley studied biology at Oberlin College, worked in several labs and earned a master's degree in science journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents