Winter solstice 2024: When does winter start?

When does winter start in 2024? Here's the science of the winter solstice, and why its the shortest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere.

The winter solstice heralds the astronomical start of winter and marks the day with the fewest hours of daylight for the year. In 2024, the winter solstice happens on Saturday, Dec. 21 at 4:21 a.m. EST in the Northern Hemisphere. But what's the science behind the shortest day and longest night?

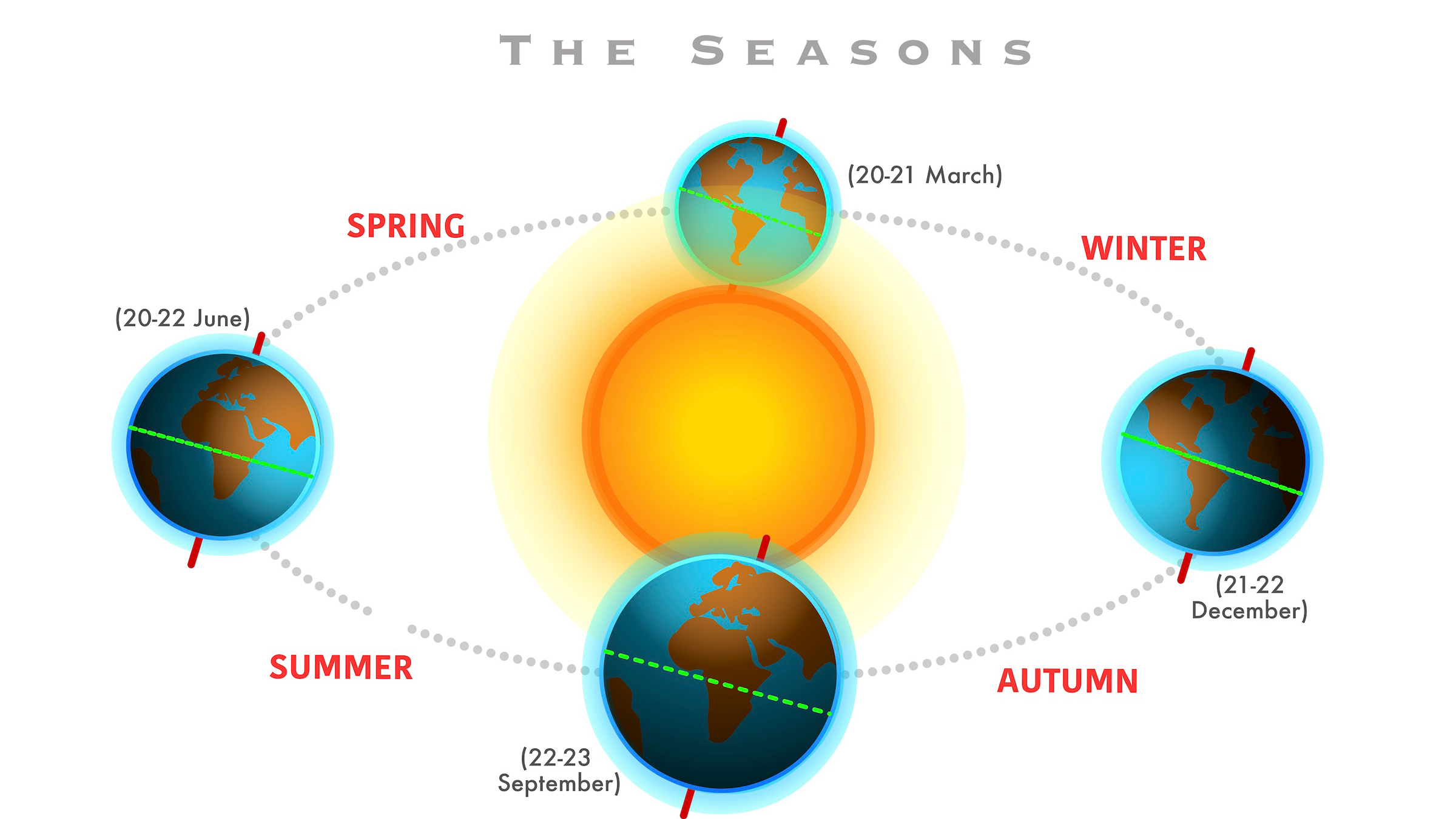

The winter solstice — and for that matter, the four seasons — occur because Earth is tilted at an angle of about 23.5 degrees relative to the sun. Instead of rotating on a straight axis, our planet is "tipped a bit," said Michael S. F. Kirk, a research astrophysicist in the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

This tilt means the Northern and Southern hemispheres receive different amounts of sunlight, and the amount of light each hemisphere gets varies throughout the year as our planet moves around the sun — which is why we experience seasons. Much of the Northern Hemisphere receives scant daylight during its wintertime months, while the Southern Hemisphere experiences the opposite — enjoying summer during the Northern Hemisphere's winter and enduring winter just as the Northern Hemisphere basks in summertime.

But although the Northern Hemisphere's winter solstice gets an entire day of recognition, it happens in an instant, when the North Pole is at its farthest tilt of 23.5 degrees away from the sun. This position leaves the North Pole beyond the sun's reach, plunging it into total darkness, Kirk said.

At the same time in the Southern Hemisphere, this moment will mark the summer solstice, or the day this year with the greatest number of daylight hours, as the South Pole will be tilted toward the sun and have more sunny exposure. "The [northern] winter solstice is when the North Pole is entirely shrouded in darkness; the South Pole is entirely bright — it's the opposite down there, it's summer," Kirk told Live Science.

What happens to the sun on the winter solstice?

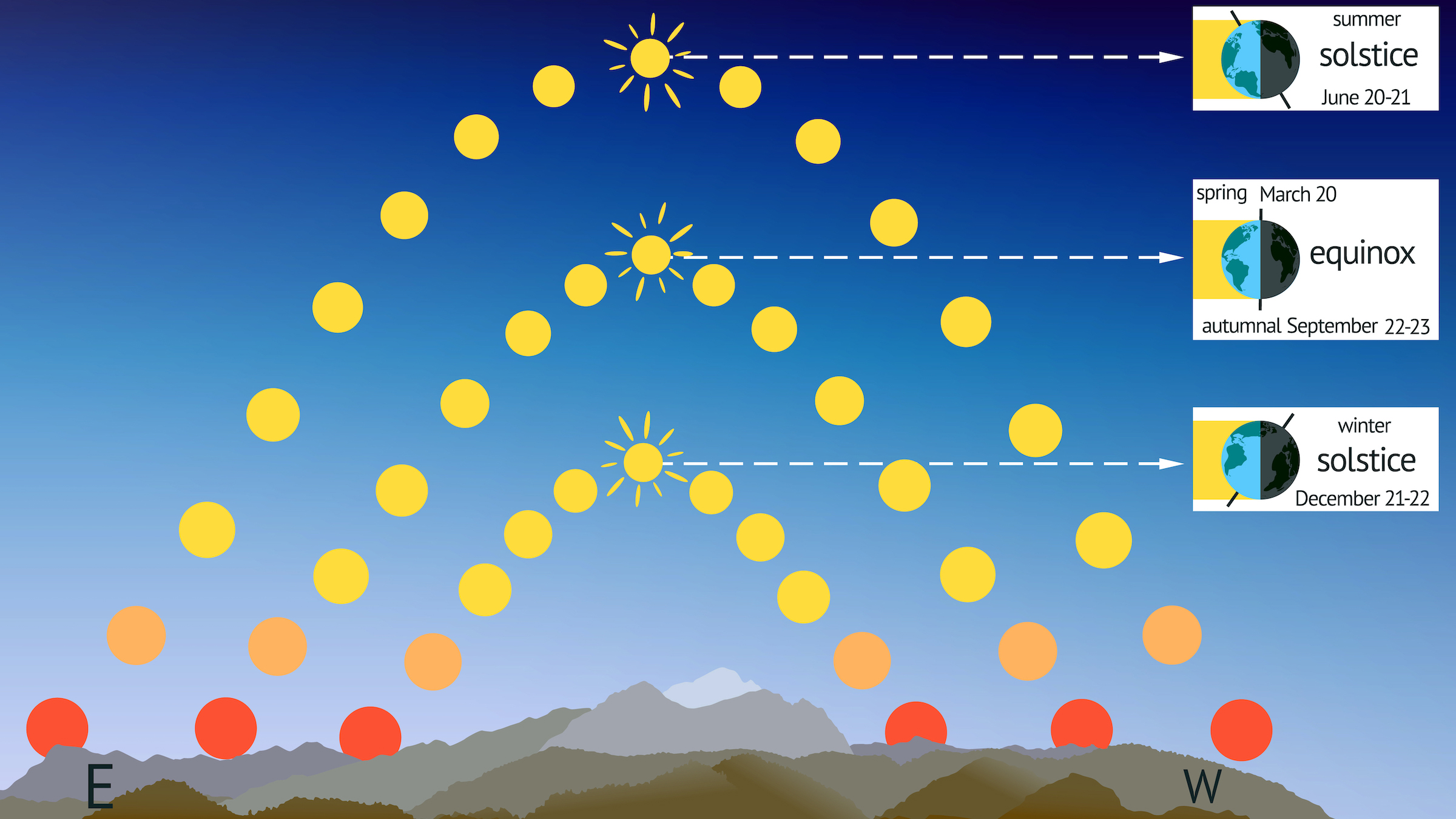

On the December winter solstice, there are fewer hours of sunlight the farther north you go in the Northern Hemisphere. People in this hemisphere might notice that the sun is not that high in the sky, even at noon.

On the equinox — the two days of the year when both hemispheres experience the same amount of daylight and nighttime — the sun appears directly overhead, at 90 degrees above the equator at noon. But on the northern winter solstice, the noon sun appears directly overhead at a lower latitude: the Tropic of Capricorn, which sits about 23.5 degrees south of the equator and runs through Australia, Chile, southern Brazil and northern South Africa. The Tropic of Capricorn is the most southerly latitude at which the sun can appear directly overhead at noon, according to the Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System, a project based at the University of Hawaii.

Because the sun reaches its zenith at noon at such a southerly latitude, at higher northern latitudes, the sun "just barely comes up over the horizon and goes back down again," Kirk said.

Why does the winter solstice date vary?

Each year, the winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere falls on one of two days: Dec. 21 or Dec. 22. In the Southern Hemisphere, the winter solstice happens on June 20 or June 21.

The date varies because the Gregorian calendar has 365 days, with an extra leap day added in February every four years. In reality, Earth's orbit around the sun takes 365.25 days, NASA reported. Due to this discrepancy, the winter solstice doesn't always occur on the same day.

Earth's distance from the sun

Some parts of the Northern Hemisphere get so cold during the wintertime, you might think that Earth is farther from the sun at this time. "Actually, it's the exact opposite," Kirk said. "In the Northern Hemisphere, winter happens when we're closest to the sun."

On average, Earth is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) from the sun, according to NASA. Earth will be closest to the sun, or at perihelion, at 8:28 a.m. EST on Jan. 4, 2025, when it will be 91,405,992 miles (147,103,686 km) from the sun, according to timeanddate.com.

Earth will be at its farthest from the sun, or at aphelion, at 3:54 p.m. EDT on July 3, 2025 when it will be 94,502,939 miles (152,087,738 km) away from our star.

How long is winter?

Astronomically, or according to the solstices and equinoxes, winter begins on the winter solstice and ends on the spring equinox. So, winter in the Northern Hemisphere lasts from Dec. 21 or 22 until March 19, 20 or 21. Because Earth has an oval, or elliptical orbit, the seasons aren't the same length; winter lasts an average of 89 days in the Northern Hemisphere and an average of 93.6 days in the Southern Hemisphere, according to timeanddate.com.

Meteorologically speaking (looking at the climate), in the U.S. winter lasts from Dec. 1 through Feb. 28 or 29, which are usually cold months in much of the country, according to Weather Underground. Using this definition, winter lasts 89 or 90 days.

What does solstice mean?

A few days before and after the solstice, the sun's trek across the sky looks so similar, it appears like it's taking the same path every day — hence the name "solstice," which means "sun stands still" in Latin, according to NASA. That's not really the case; the sun's path is slightly different on these days, but it can be hard to notice without modern instruments.

Why isn't the winter solstice the coldest day?

If there's such little sunlight in the Northern Hemisphere during the winter solstice, why isn't it the coldest day of the year?

"The most intuitive way [to understand it] is that it takes time for everything to cool off," Kirk said. "The sun is getting less radiation, less heat down on the Earth. It takes a long time for the Earth and the oceans to radiate all that energy out and cool off from all of that lack of sunlight."

Once the land and the oceans cool off, it can take weeks or months for them to heat up again. After the winter solstice, the days begin to get longer in the Northern Hemisphere. But the sun still doesn't shine as long as it does in summertime; for instance, northern midlatitudes experience about 9 hours of daylight in the weeks following the solstice, compared with the roughly 15 hours of daily sunlight they get around the summer solstice. In addition, the Northern Hemisphere is still tilted away from the sun, making it chilly.

When is the winter solstice?

| Year | Northern Hemisphere winter solstice | Southern Hemisphere winter solstice |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 4:19 am EST Dec. 21 | June 20 |

| 2025 | 10:02 am EST Dec. 21 | June 20 |

| 2026 | 3:49 pm EST Dec. 21 | June 21 |

Winter solstice celebrations

Many cultures have recognized the winter solstice. The most famous prehistoric site that ties in with the solstice is at Stonehenge in England. When the sun sets on the shortest day of the year, the sun's rays align with Stonehenge's central Altar stone and Slaughter stone, which may have had spiritual significance to the people who built the monument.

In Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, the ancient stonewalled Mayan city of Tulum also has a structure honoring the solstices. When the sun rises on the winter and summer solstices, its rays shine through a small hole at the top of one of the stone buildings, which creates a starburst effect.

"I think there's a deep connection between our lives as humans and the amount of daylight and the seasonal patterns that we experience," Kirk said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

- Brandon SpecktorEditor