Massive disk galaxy could change our understanding of how galaxies are born

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

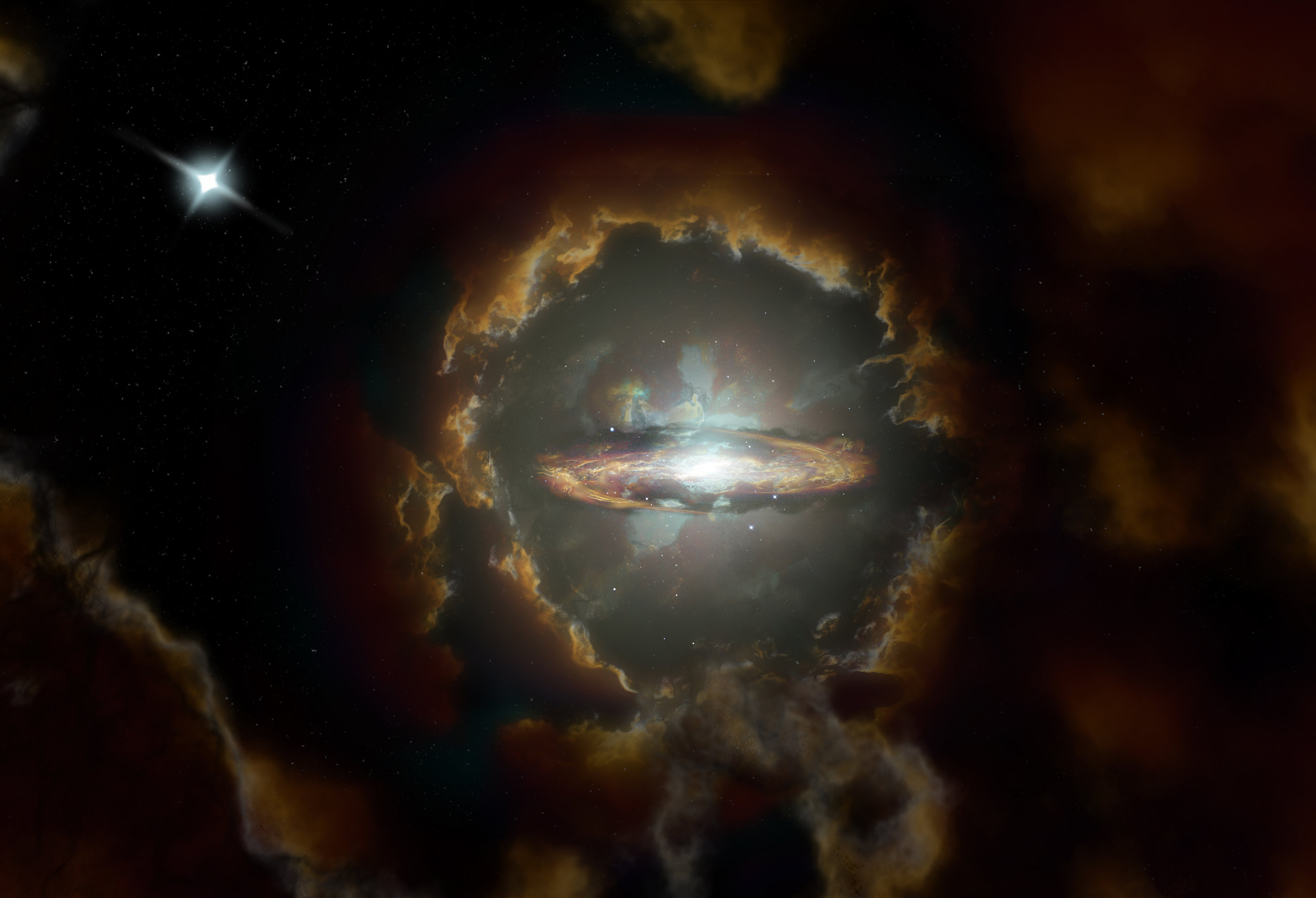

A massive, rotating disk galaxy that first formed just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, could upend our understanding of galaxy formation, scientists suggest in a new study.

In traditional galaxy formation models and according to modern cosmology, galaxies are built beginning with dark-matter halos. Over time, those halos pull in gases and material, eventually building up full-fledged galaxies. Disk galaxies, like our own Milky Way, form with prominent disks of stars and gas and are thought to be created in a method known as "hot mode" galaxy formation, where gas falls inward toward the galaxy's central region where it then cools and condenses.

This process is thought to be fairly gradual, taking a long time. But the newly discovered galaxy DLA0817g, nicknamed the "Wolfe Disk," which scientists believe formed in the early universe, suggests that disk galaxies could actually form quite quickly.

Related: Milky Way Quiz: Test Your Galaxy Smarts

In a new study led by Marcel Neeleman of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, researchers spotted the Wolfe Disk using ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile. They found out that the object was a large, stable rotating disk, clocking in at a whopping 70 billion times the mass of our sun.

In the new observations, the disk appears as it was when the universe was just 1.5 billion years old, or 10% of its current age. The disk appears extremely massive and stable for something so young. So how could such a massive galaxy form so quickly, so early in the universe?

Researchers suggest that the galaxy might have formed by a process known as "cold-mode accretion." They think that the gas falling in towards the galaxy's center was actually cold so, because the gas didn't need time to cool down as it approached the galactic center, the disk was able to more rapidly condense.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The result provides valuable input for a present-day discussion about how galaxies form," according to a statement from the Max Planck Institute.

However, astrophysicist Alfred Tiley noted in a Nature News & Views article accompanying this study, these findings are based off of a single galaxy. He emphasized that more similar observations would be needed to validate this hypothesis.

This work was published Wednesday (May 20) in the journal Nature.

- Get Ready for Milky Way Season with These Galactic Night-Sky Photos

- Pretty Panoramic Milky Way Photo Resembles an Astronaut's-Eye View

- The Universe Reveals Its True Colors in This Stunning Milky Way Photo

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Chelsea Gohd joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2018 and returned as a Staff Writer in 2019. After receiving a B.S. in Public Health, she worked as a science communicator at the American Museum of Natural History. Chelsea has written for publications including Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine, Live Science, All That is Interesting, AMNH Microbe Mondays blog, The Daily Targum and Roaring Earth. When not writing, reading or following the latest space and science discoveries, Chelsea is writing music, singing, playing guitar and performing with her band Foxanne (@foxannemusic). You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus