6 times that 2020 showed us women from antiquity were totally badass

Women of the ancient world were not to be trifled with.

Throughout history, women have been fighters, strategists and charismatic leaders, performing feats of strength, cunning and bravery. And in 2020, archaeologists uncovered intriguing evidence from the past showing that women didn't hesitate to kick butt and take names. From hoisting a spear to hurling a vengeful spell, here are six times that women from antiquity showed us that they were not to be trifled with.

Inspiration for 'Mulan'

Two women — one about 50 years old and the other about 20 — who were buried in Mongolia during the Xianbei period (A.D. 147 to 552) possibly inspired the famed "Ballad of Mulan," about a girl who served in the military in her father's place. Though the Ballad of Mulan was first transcribed by Chinese writers, tales of her brave deeds may have originated in what is now Mongolia; she is described in the ballad as serving the "khan," a term reserved for Mongolian leaders, and China did not have military conscription at the time, the researchers said. The Mongolian women's skeletal remains revealed that they were expert archers and horseback riders, and they likely fought alongside men.

Read more: Two 'warrior women' from ancient Mongolia may have helped inspire the Ballad of Mulan

Big game hunter

A 9,000-year-old burial of a female hunter sparked an investigation upending the long-held notion that men were the primary hunters in ancient hunter-gather societies, while women were relegated to collecting herbs and plants. When researchers excavated the grave in the Andes Mountains in southern Peru, they found a hunting "toolkit" near the skeleton containing multiple projectile weapons, hinting that the person was a skilled hunter and respected as such by their community. Though the remains were initially thought to belong to a man, further analysis of the bones and teeth revealed that the hunter was female.

"These findings sort of underscore the idea that the gender roles that we take for granted in society today — or that many take for granted — may not be as natural as some may have thought," said lead author Randy Haas, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis.

Read more: Ancient burial of fierce female hunter (and her weapons) discovered in Peru

Road warrior

A paved 1,000-year-old limestone road connecting two ancient Mayan cities may have been built by a ruthless queen named Lady K'awiil Ajaw, so that she could expand her regional power. She ruled in Cobá in what is now Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula, and archaeologists recently reported that the Mayan queen constructed the road in order to invade a town about 60 miles (100 kilometers) to the west, called Yaxuná, which had been steadily growing in strength and threatened her rule.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using lidar (light detection and ranging), a remote-sensing method using laser pulses to measure distances, the researchers analyzed the ancient "white road." Earlier surveys declared that the road ran in a straight line between Cobá and Yaxuná. But the new analysis revealed unexpected twists and turns in the so-called white road that likely encompassed small settlements, which the queen's forces would also have conquered on her path to victory.

Read more: Maya warrior queen may have built the longest 'white road' in the Yucatán

Polo champ

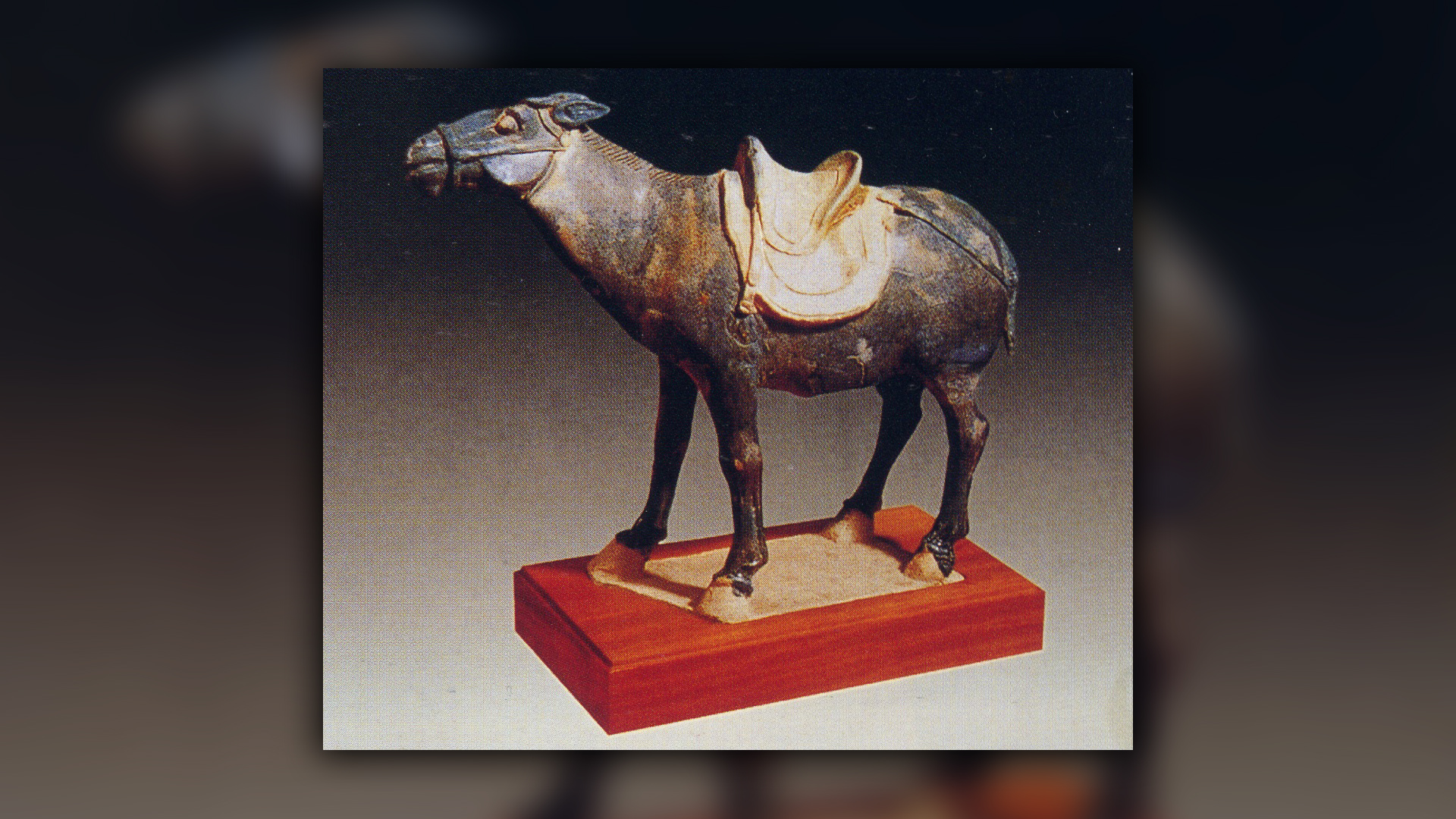

The burial of a noblewoman named Cui Shi from ancient China included donkeys, perhaps so that she could play polo in the afterlife. Because Cui Shi was wealthy and a member of the elite, the donkeys in her tomb likely served a more important purpose in her household than merely a means of carrying heavy loads.

Archaeologists discovered Cui Shi's tomb in 2012, and recent analysis of the donkeys' leg bones confirmed that they had a different gait than pack animals did, hinting that they were bred for quick maneuvering during high-speed polo games. Records from this period during the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618 to 907) show that polo was popular among imperial China's upper classes, despite the game's dangers; one historic account notes that Cui Shi's husband lost an eye during a polo match.

Read more: First proof of donkey polo in ancient China found in noblewoman's tomb

Under her spell

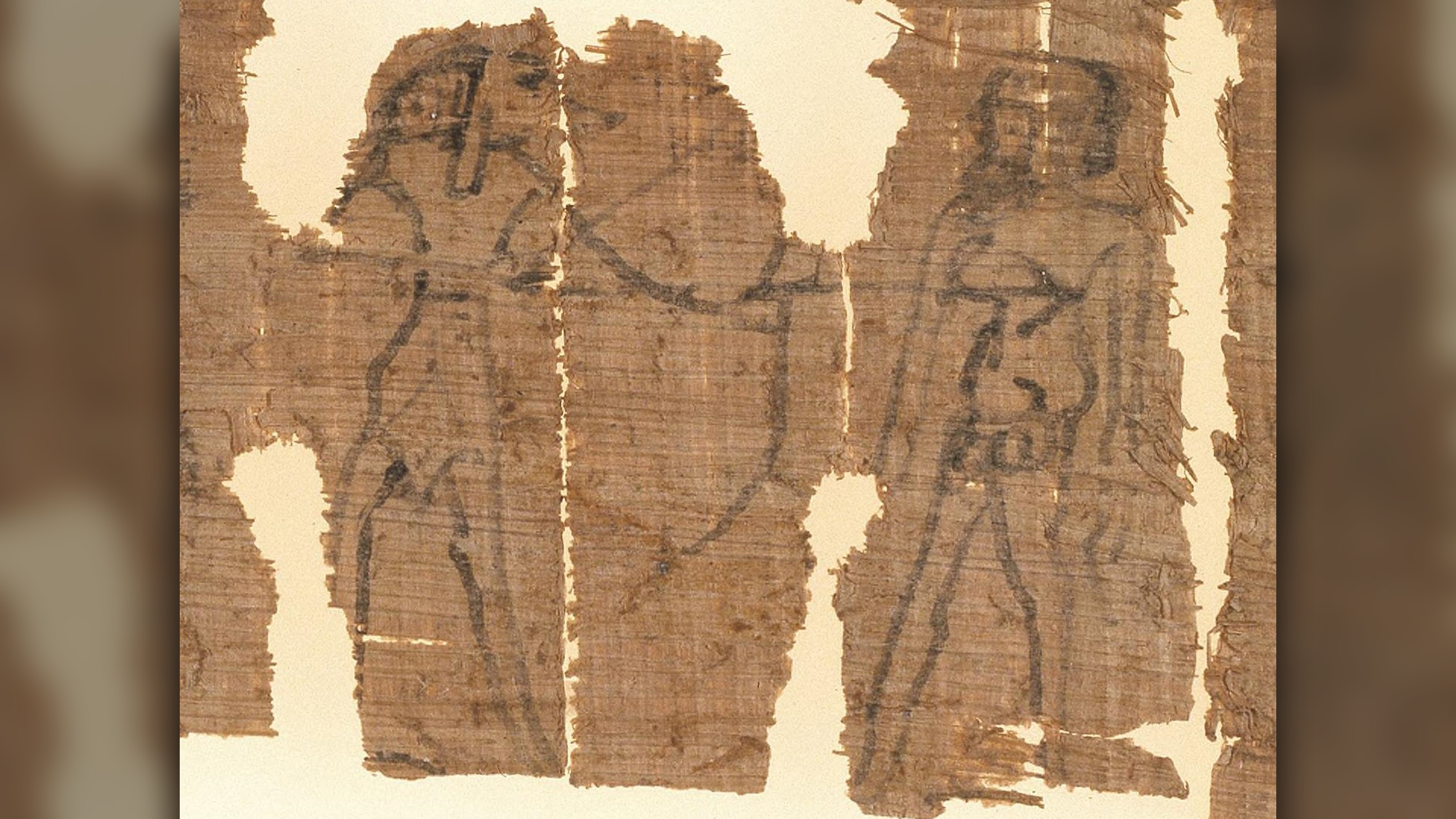

About 1,800 years ago in ancient Egypt, a lovestruck woman named Taromeway commissioned an "erotic binding spell" to drive a man named Kephalas mad with lust — the spell was documented in a papyrus scroll, which researchers recently translated. It called upon a ghost to hound Kephalas until he gave in to Taromeway, with "his male organs pursuing her female organs," according to the spell. The scroll also contained a drawing of Kephalas in the nude, with the Egyptian jackal-headed god Anubis firing an arrow at the naked man (presumably to inflame Kephalas' desire for Taromeway). Scholars have translated binding spells like this one before, but such spells are typically used by men to attract women, the scientists reported.

Read more: Woman seeks man in ancient Egyptian 'erotic binding spell'

Daggers, knives and an axe

A 2,500-year-old burial in Siberia holds a woman warrior and her weapons stash, including an axe, knives and bronze daggers. There are four bodies in total in the grave — the woman, a man, an older woman and an infant — and they belonged to the ancient Tagar culture, a subset of southern Siberia's nomadic Scythian civilization. The woman was likely in her 30s or 40s when she died, and she was arranged on her back with her set of weapons positioned close by. Tagarian women were often buried with long-range weapons, so the presence of a melee-style long-handled battle axe is very unusual, one of the archaeologists said.

Read more: Ancient Siberian grave holds 'warrior woman' and huge weapons stash

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.