Researchers may have pinpointed the source of a famous supposed alien broadcast discovered nearly a half century ago.

The prominent and still-mysterious Wow! Signal, which briefly blared in a radio telescope the night of Aug. 15, 1977, may have come from a sun-like star located 1,800 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius.

"The Wow! Signal is considered the best SETI candidate radio signal that we have picked up with our telescopes," Alberto Caballero, an amateur astronomer, told Live Science. SETI, or the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, is a field that has been listening for possible messages from otherworldly technological beings since the middle of the 20th century, according to NASA.

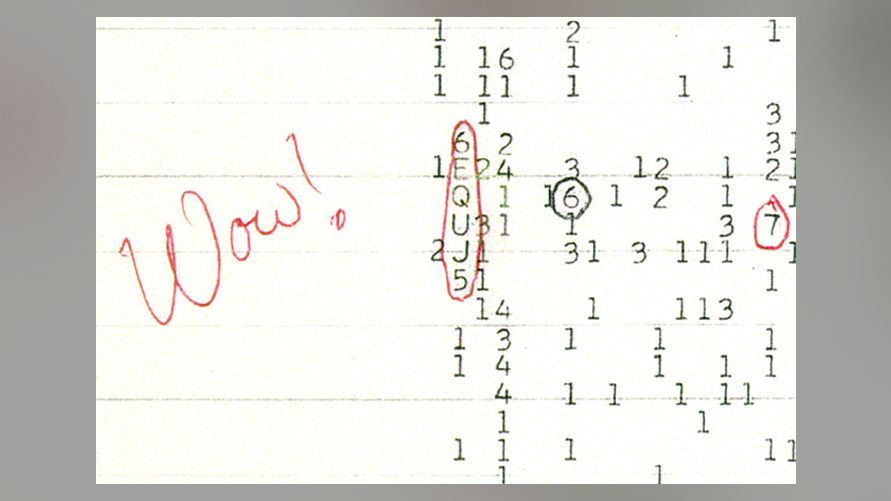

Appearing during a SETI search at the Ohio State University's Big Ear telescope, the Wow! Signal was incredibly strong but very brief, lasting a mere 1 minute and 12 seconds, according to a report written by its discoverer, astronomer Jerry Ehman, in honor of its 30th anniversary.

Upon seeing a printout of an anomalous signal, Ehman scribbled "Wow!" on the page, giving the event its name. The now-deconstructed Big Ear telescope looked for messages at the electromagnetic frequency band of 1420.4056 megahertz, which is produced by the element hydrogen.

Related: 9 things we learned about aliens in 2021

"Since hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, there is good logic in guessing that an intelligent civilization within our Milky Way galaxy desirous of attracting attention to itself might broadcast a strong narrowband beacon signal at or near the frequency of the neutral hydrogen line," Ehman wrote in his anniversary report.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers have since repeatedly searched for follow-ups originating from the same place, but they have turned up empty, according to a history from the American Astronomical Society. The Wow! Signal most likely came from some kind of natural event and not aliens, Caballero told Live Science, though astronomers have ruled out a few possible origins like a passing comet.

Still, Caballero noted that in our infrequent attempts to say hello to E.T., humans have mostly produced one-time broadcasts, such as the Arecibo message sent toward the globular star cluster M13 in 1974. The Wow! Signal may have been something similar, he added.

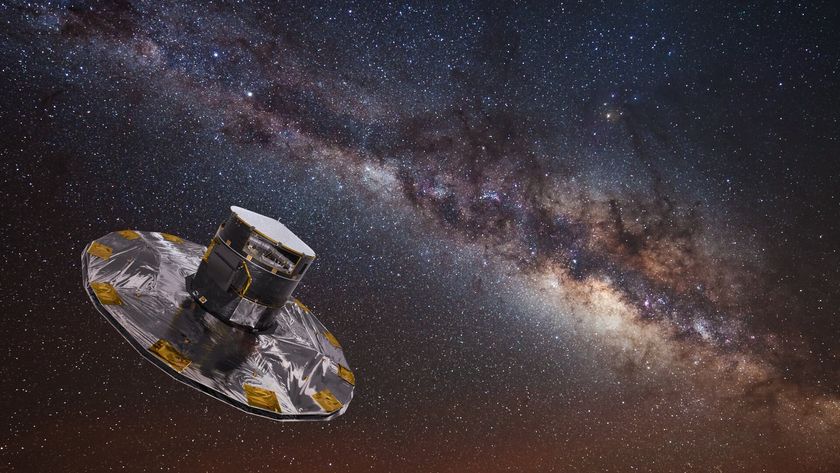

Knowing that the Big Ear telescope's two receivers were pointing in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius on the night of the Wow! Signal, Caballero decided to search through a catalog of stars from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite to look for possible candidates.

"I found specifically one sun-like star," he said, an object designated 2MASS 19281982-2640123 about 1,800 light-years away that has a temperature, diameter and luminosity almost identical to our own stellar companion. Caballero's findings appeared May 6 in the International Journal of Astrobiology.

While living organisms may exist in a wide variety of environments around stars quite dissimilar to our own, he chose to focus on sun-like stars because "we're looking for life as we know it." Given his results, he thinks it "could be a good idea to search [the star] for habitable planets, and even civilizations."

"I think this is perfectly worth doing because we want to point our instruments in the direction of things we think are interesting," Rebecca Charbonneau, a historian who studies SETI at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and who wasn't involved in the work, told Live Science. "There are billions of stars in the galaxy, and we have to figure out some way to narrow them down," she added.

But she wonders if looking for only sun-like stars is too limiting. "Why not just look at a bunch of stars?" she asked.

Humans have only one data point, ourselves, when considering what types of technology aliens may have, or how they might use that technology, Charbonneau said. The concept of SETI itself appeared in the middle of the 20th century, shortly after militaries around the world began broadcasting messages using powerful electromagnetic instruments.

"I don't think it’s a coincidence that the point in human history where we start putting intelligent signals in space is also the same point in history where we get the idea to look for intelligent signals from space," Charbonneau said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.