Mass grave from Nazi atrocity discovered in Poland's 'Death Valley'

Among the victims were members of the Polish resistance.

Archaeologists in Poland have discovered a mass grave that the Nazis tried to destroy at the end of World War II, a new study finds.

The mass grave, filled with the remains of about 500 individuals, is linked to the horrific "Pomeranian Crime" that took place in Poland's pre-war Pomerania province when the Nazis occupied the country in 1939. The Nazis killed up to 35,000 people in Pomerania at the beginning of the war, and they returned in 1945 to kill even more people, as well as to hide evidence of the prior massacres by exhuming and burning the bodies of victims.

Despite this elaborate Nazi cover-up, archaeologists have now found abundant evidence of one of these mass graves after examining archives, interviewing locals and conducting extensive archaeological surveys, the researchers said.

Related: Photos: Escape tunnel at Holocaust death site

The 1939 Pomeranian Crime was the first large-scale atrocity of World War II in Poland. This includes 12,000 people who were killed in the forests around the village of Piaśnica and 7,000 people who were buried in the forests near the village of Szpęgawsk in 1939. Some historians say the massacres were a prelude to the later Nazi atrocities committed during the Holocaust, the researchers said.

So many people were killed in 1939 and 1945 in one area of Pomerania, near the outskirts of the town of Chojnice, it became known locally as Death Valley. One witness, who testified after the war, recalled seeing that "a column of approximately 600 Polish prisoners from Bydgoszcz, Toruń, Grudziad̨z and neighboring villages, under the escort of the Gestapo, was taken to Death Valley during the second half of January 1945," the researchers wrote in the study. "They were executed there, and the witness speculated that the bodies of the victims were burned to cover up the evidence."

After the war, in 1945, exhumations at that spot in Death Valley unearthed the remains of 168 people. But it was evident from the exhumation reports and the witness' testimony that there were more burials to be found, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was commonly known that not all mass graves from 1939 were found and exhumed, and the grave of those killed in 1945 was not exhumed either," study lead author Dawid Kobiałka, an archaeologist and cultural anthropologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences, said in a statement.

To investigate, Kobiałka and his colleagues used noninvasive techniques to study the area, including with lidar (light detection and ranging), which uses lasers shot from an aircraft flying overhead to map the topography of the ground. The lidar work revealed trenches that the Polish army had dug in 1939 in anticipation of a war with the Third Reich. But just a few months later, the Nazis used these trenches to hide the bodies of their victims, the researchers said.

"Executions took place at the trenches," they wrote in the study. "The victims fell into the trenches or their bodies were thrown there by the perpetrators. Later, the trenches were backfilled with soil."

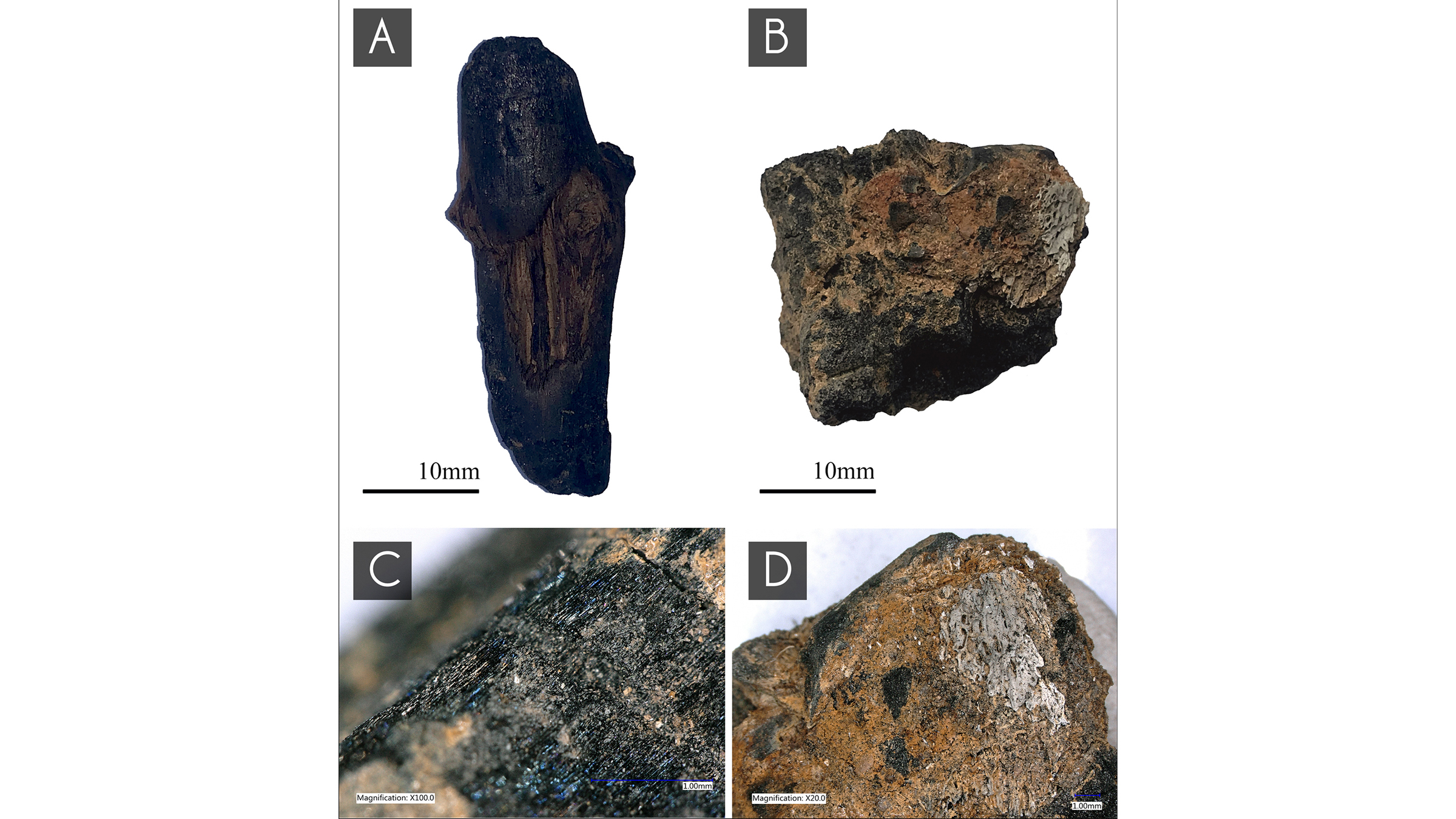

At the trench site, the team performed surveys on the soil underground with ground-penetrating radar, electromagnetic field analysis and electrical resistivity, and found many anomalies hidden in the soil underground. Metal-detector surveys also revealed many artifacts, which led the researchers to excavate eight of the trenches. Since then, they have found more than 4,250 artifacts, many from 1939 and 1945, that included bullets, shell casings and charred wood that was likely used to burn the bodies.

The team also found cremated bones and jewelry, including a gold wedding ring, suggesting the victims were not robbed when they were killed. The researchers identified the ring's owner as Irena Szydłowska, a courier in the Polish Home Army. "Her family was informed about the finding, and the plan is to return the ring to them," Kobiałka said.

Their historical investigation revealed that some of the killed prisoners were part of the Polish resistance.

"A series of specialized analyses of the finds is taking place right now," Kobiałka said. "It is believed that more victims killed in Death Valley will be identified soon, and their families will be informed about what really happened to their beloved ones."

The team also hopes to identify some of the victims with DNA analysis. After the researchers are done examining the site, "the remains will be reburied in Death Valley and the site will become an official war cemetery," they wrote in the study.

The study was published online Wednesday (Aug. 18) in the journal Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.