Is the Yellowstone supervolcano really 'due' for an eruption?

Yellowstone's supervolcano last erupted 70,000 years ago. Will it erupt again anytime soon?

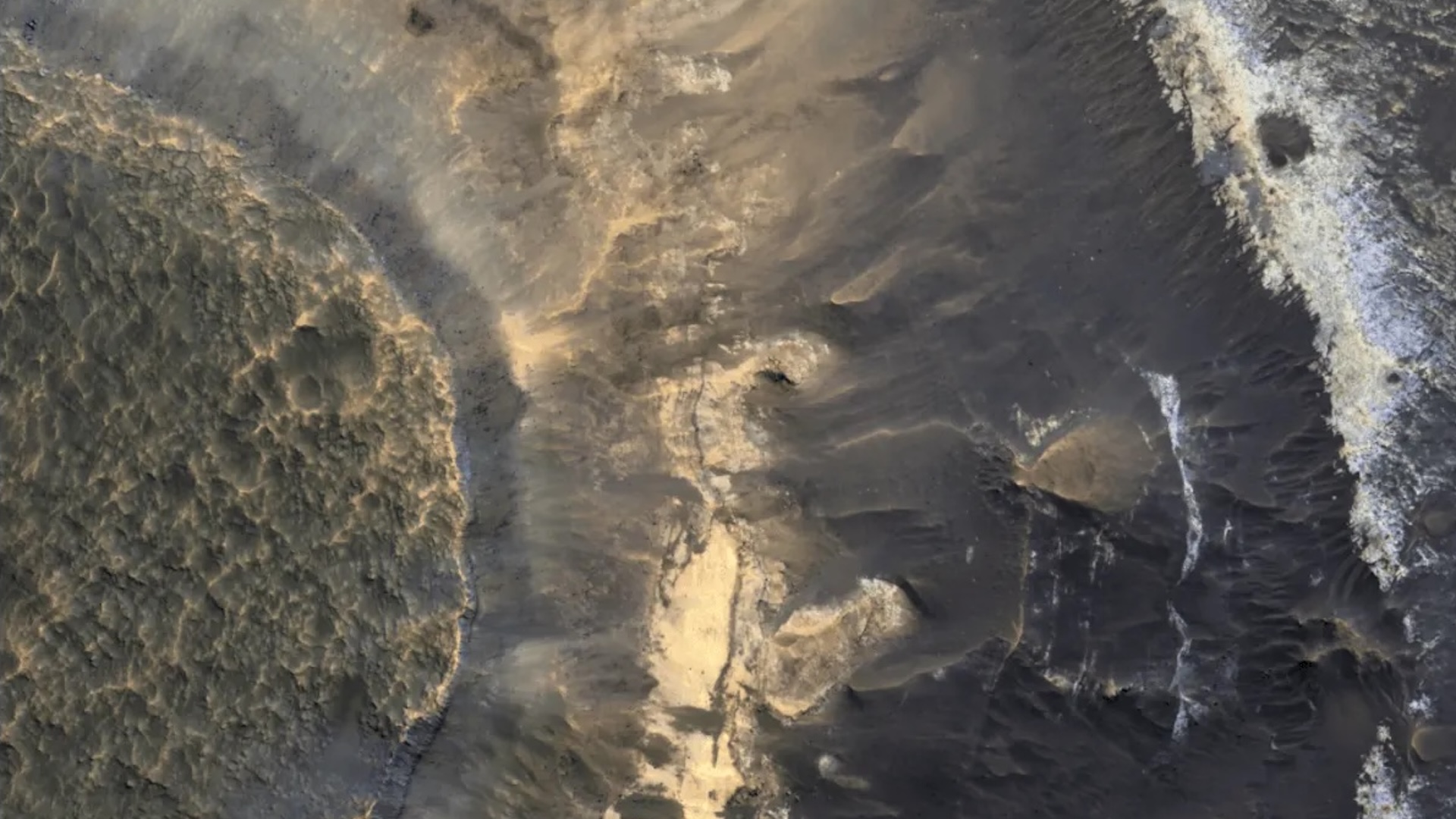

Beneath Yellowstone National Park, a vast region of spectacular wilderness visited by around 3 million people annually, lurks one of the largest volcanoes in the world.

The Yellowstone Caldera — the cauldron-like basin at the summit of the volcano — is so colossal that it is often called a "supervolcano," which, according to the Natural History Museum in London, means it has the capacity to "produce a magnitude-eight eruption on the Volcanic Explosivity Index, discharging more than 1,000 cubic kilometers [240 cubic miles] of material."

To put that into perspective, the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo in the Philippines, arguably the most powerful volcanic eruption in living memory, was rated a 6 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index, making it, according to the Natural History Museum, "around 100 times smaller than the benchmark for a supervolcano."

So should we be worried? Will Yellowstone erupt anytime soon?

Is Yellowstone "due" for an eruption?

Media reports have often claimed that Yellowstone is due to erupt. They claim that because the last eruption of the supervolcano was 70,000 years ago, it's bound to blow soon. But that's not how volcanoes work.

"This is perhaps the most common misconception about Yellowstone, and about volcanoes in general. Volcanoes don't work on timelines," Michael Poland, a geophysicist and the scientist-in-charge at Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, told Live Science in an email. "They erupt when there is enough eruptible magma beneath the surface, and pressure to cause that magma to ascend.

"Neither condition is in place at Yellowstone right now," he added. "It's all about that magma supply. Cut that off, and the volcano won't erupt."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many volcanoes go through cycles of activity and inactivity, Poland said. More often than not, a volcano's activity is a direct consequence of the magma supply. "Some volcanoes do seem to have regular eruptions, but this is because the magma supply is relatively constant — think Kilauea in Hawaii or Stromboli in Italy," Poland said.

Related: The 11 biggest volcanic eruptions in history

So where does the idea of Yellowstone being "overdue" for an eruption come from, then?

"I suspect the 'overdue' idea comes from the concept of earthquakes," Poland said. "Earthquakes happen as stress accumulates on faults, and in many places this stress accumulates at relatively constant rates due to, for example, plate motion. That being the case, you might expect earthquakes to occur at somewhat regular intervals. It is, of course, more complicated than that — there are many variables at play — but for that reason, it makes more sense to say that a fault is 'overdue' for an earthquake."

Poland also noted that "supervolcanoes" — a term he considers somewhat crude and sensationalist — are "no more or less temperamental" than other volcanoes. So, how do experts keep an eye on Yellowstone's subterranean activity so that, in the case of a major volcanic eruption, warnings can be given?

"Yellowstone is very well monitored by a variety of techniques," Poland said. "It is covered in terms of seismicity and ground deformation. We track the temperatures of some thermal features, although this is not an indicator of volcanic activity, but rather of the behavior of specific hydrothermal areas. We look at overall thermal emissions from space, collect gas and water to assess chemistry over time, and track stream/river flow and chemistry."

So what might indicate that a massive eruption is imminent?

"Having thousands of earthquakes in a short period of time (a few weeks), with many felt events, would be noteworthy, as long as it was not an aftershock sequence from a tectonic event," Poland said. "That seismicity would need to be coupled with really extreme ground deformation (tens of centimeters over the same short period), park-wide changes in geyser activity, and thermal/gas emissions. The ground rises and falls normally by 2-3 cm [0.8 to 1.2 inches] every year, and there are typically ~2000 quakes annually in the area, so it would have to rise far beyond these normal background levels."

While Yellowstone is relatively stable right now and has not displayed any unusual seismic activity lately, if it were to erupt, the consequences could be extreme. Volcanologists have suggested that the ramification they are most concerned about is wind-flung ash, which could end up coating a surrounding region 500 miles (800 kilometers) across in more than 4 inches (10 centimeters) of ash. This could, experts predict, result in the short-term destruction of Midwest agriculture, and would leave scores of watercourses clogged. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, "the surrounding states of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming that are closest to Yellowstone would be affected by pyroclastic flows, while other places in the United States would be impacted by falling ash." Poland added that the effects would also be felt beyond the United States' borders.

"If there were a very large explosive eruption, it could impact the global climate by emitting ash and gas into the stratosphere, which could block sunlight and lower global temperatures by a few degrees for a few years," Poland explained.

Research published in the journal Science in December 2022 found that the Yellowstone caldera holds more liquid molten rock than previously estimated. Given that volcanoes tend to erupt only when a vast amount of magma is readily available, should this finding be a cause for concern?

"This [research] really just confirms what we already know about Yellowstone," Poland said. "Initial findings were that the magma chamber beneath Yellowstone was only 5-15% molten. The new research, which uses more advanced techniques but the same data, suggests it is closer to 16-20% molten. The take-home message is that the magma chamber is mostly solid. And that means there is far less likelihood of a consequential eruption. I find this result reassuring."

Joe Phelan is a journalist based in London. His work has appeared in VICE, National Geographic, World Soccer and The Blizzard, and has been a guest on Times Radio. He is drawn to the weird, wonderful and under examined, as well as anything related to life in the Arctic Circle. He holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Chester.