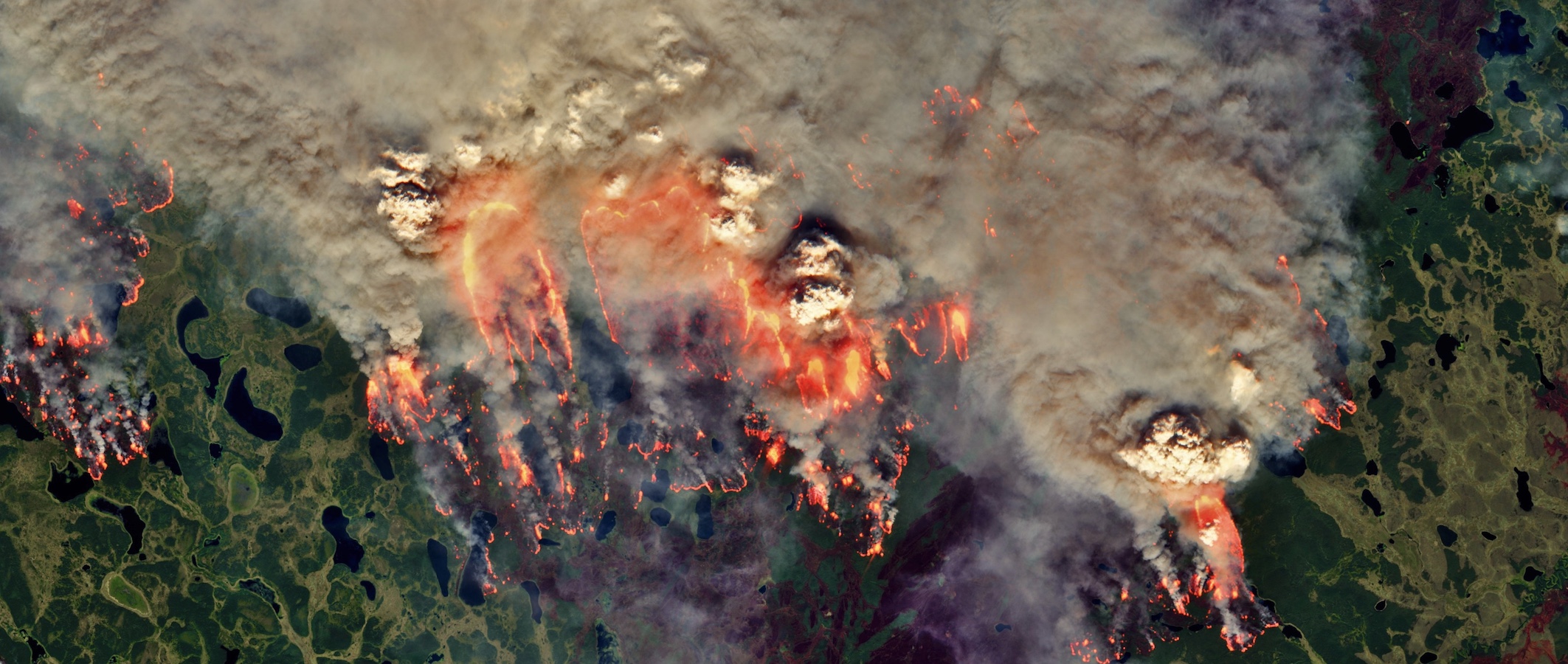

Zombie wildfires are blazing through the Arctic, causing record burning

The Arctic wildfire season has been the worst since record-keeping began.

"Zombie" wildfires that were smoldering beneath the Arctic ice all winter suddenly flared to life this summer when the snow and ice above it melted, new monitoring data reveals.

And this year has been the worst for Arctic wildfires on record, since reliable monitoring began 17 years ago. Arctic fires this summer released as much carbon in the first half of July than a nation the size of Cuba or Tunisia does in a year.

That's according to monitoring by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, the European Union's Earth-monitoring organization. More than 100 fires have burned across the Arctic since early June, according to Copernicus. "Obviously it's concerning," Copernicus senior scientist Mark Parrington told the BBC. "We really hadn't expected to see these levels of wildfires yet."

Related: In photos: Devastating look at raging wildfires in Australia

Zombie fires

The "zombie fires" tracked by Copernicus were likely smoldering beneath the ice and snow in the carbon-rich peat of the Arctic tundra. When the ice and snow melt, these hotspots can ignite new wildfires in the vegetation above.

"The destruction of peat by fire is troubling for so many reasons," Dorothy Peteet, a a senior research scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, told Earth Observatory. "As the fires burn off the top layers of peat, the permafrost depth may deepen, further oxidizing the underlying peat."

The fires then release carbon and methane from the peat, both greenhouse gases that further contribute to the warming of the planet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But zombie fires aren't the only cause for the rough wildfire season; lightning strikes and human behavior are also causing conflagrations.

Parrington and his colleagues had previously tracked the vicious wildfire season of 2019, but were surprised at how the fires intensified this year over the course of July, Parrington told Earth Observatory.

Siberia wasn't the only wildfire hotspot in the Arctic this summer. Northern Alberta, Canada has also been particularly impacted. The Chuckegg Creek Fire in northern Alberta, for example, burned more than 1,351 square miles (350,134 hectares) and took three months to contain, according to Global News Canada.

Fire season

The Arctic fire season runs from May to October, with the worst fires usually occurring between July and August. The 2019 fire season broke records for the number of fires and carbon released, with Copernicus reporting that in June alone, the fires released 50 megatonnes of carbon dioxide.

The 2020 fires are already outpacing 2019's conflagrations. All told, Copernicus estimates that between January and August, the fires released 244 megatonnes of carbon. That's more than the entire nation of Vietnam released in 2017. The fires also release other pollution that has worsened air quality in Europe, Russia and Canada, according to Copernicus. Earth scientists are expecting similar conditions for 2021 and beyond.

"We know that temperatures in the Arctic have been increasing at a faster rate than the global average, and warmer/drier conditions will provide the right conditions for fires to grow when they have started," Parrington said in a statement released by Copernicus, adding, "Our monitoring is important in raising awareness of the wider scale impacts of wildfires and smoke emissions which can help organizations, businesses and individuals plan ahead against the effects of air pollution."

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.