Older people don't take more precautions against coronavirus

Older people, who are far more likely to experience severe illness or die from the new coronavirus than younger people, aren't taking more preventive measures to avoid infection, a new international study finds.

Using survey data from 27 countries, researchers found that age has no impact on how likely people are to follow recommendations such as avoiding crowds, wearing face masks and shunning shops and other trips away from home. People in their 70s and 80s are no more likely to self-isolate than those in their 50s and 60s.

"This is very surprising because it is exactly that subpopulation (the 60+ year-olds) that should be, according to public health agencies around the world, more careful when it comes to self-isolation," study author Jean-François Daoust, a political scientist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, wrote in an email to Live Science.

Overall, willingness to self-isolate and take other preventative measures was high across all age groups, so it's not clear how much the lack of additional caution by the oldest individuals might affect the spread of SARS-CoV-2. It depends on other factors, Daoust said: For example, if an older individual who sees very few people normally refuses to self-isolate completely, their chances of spreading the disease might not change much. If that person is a social butterfly, their reluctance could have a larger impact.

Related: Latest updates on COVID-19

Age and COVID-19

I would make the following parallel: How is it that you voted in most of the elections in your life, if not always, because you see it as a duty, part of a collective action, but that you do not see your current behavior as an important duty to protect yourself and others?

Jean-François Daoust

Age has emerged as a clear risk factor for sickness and death from SARS-CoV-2 infection. A paper published June 16 in the journal Nature Medicine estimates that while 21% of infected 10- to 19-year-olds show symptoms, about 69% of infected individuals over 70 do. In New York City's outbreak, those over 75 have made up almost half of all COVID-19 deaths as of May 12, while those ages 65 to 74 made up another quarter of deaths. Only about 4% of New York's fatalities in mid-May were individuals18 to 44 years old.

Given this risk, you might expect older people would be the most cautious about avoiding infection. And in a survey done in March, the Pew Research Center did find that older Americans were more likely to see the disease as risky to their personal health compared with how younger Americans viewed their own risk. But many coronavirus opinion surveys have questioned a relatively small number of older adults, and most use linear models to explore the effect of age. What this means is that the statistics provide an average across the entire age span, even if subgroups look very different from one another.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, Daoust said, imagine that every additional year of age was linked with a 5-point increase in coronavirus concern on a hypothetical scale for 18- to 35-year-olds, with a 10-point increase among 35- to 60-year-olds and with a 1-point increase for those over 60. Averaging 5, 10 and 1 across the three groups would yield 5.3, suggesting that each year of life between 18 to 60+ would raise coronavirus concerns by 5 points.

Related: Why COVID-19 kills some people and spares others

That average is accurate for the 18- to 35-year-olds, but way off for the 35- to 60-year-olds and especially for those over 60. A statistical method that doesn't require a linear result could yield a more accurate picture, showing the differences in how age impacts concern in different phases of life, Daoust said.

Daoust's dataset came from polling conducted by The Institute of Global Health Innovation (IGHI) at Imperial College London and the polling company YouGov in 27 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, United Arab Emirates (UAE), United Kingdom (UK), United States (USA) and Vietnam. The surveys, conducted repeatedly since April, are nationally representative for each country, and 72,417 people have responded.

Attitudes by age

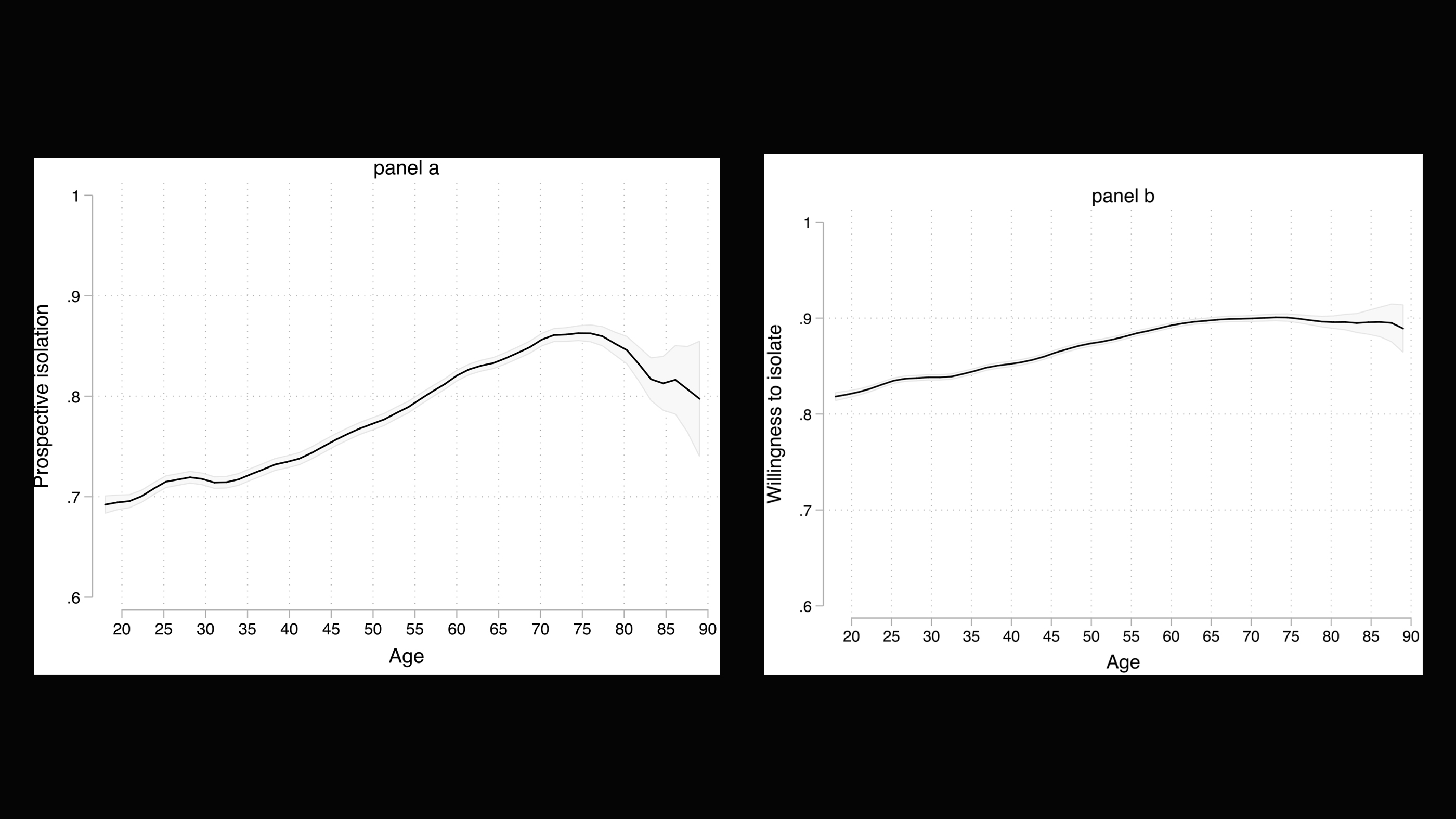

The surveys asked people about their willingness to self-isolate should they experience possible COVID-19 symptoms, as well as their willingness to self-isolate if advised to do so by a health authority. They also answered questions about a suite of preventive behaviors, including hand-washing, mask-wearing, and the avoidance of gatherings, crowds, shops and public transportation. Willingness was ranked on a scale of 0 to 1, with 0 being "not at all" and 1 being "always."

The age breakdown showed that willingness to self-isolate if experiencing symptoms rose from 0.7 at age 20 to about 0.85 at age 70, then flattened and declined to 0.8 by age 90 — back to the same level seen in 50-year-olds, who are at much less risk than someone in their 80s. In a more stable but similar pattern, willingness to isolate if told to by a medical or health authority crept up slightly from just over 0.8 at age 20 to just under 0.9 at age 60 and then stalled out.

Daoust combined the other 16 preventive measures into a single scale and found that when it comes to following social-distancing and hygiene recommendations, age is not a factor at all. Though youth have a reputation for incautious behavior, Daoust said, "everyone seems to respect the preventive measures to the same degree." (Overall, the respect was relatively high, with people reporting engaging in 12 out of 16 behaviors, on average.)

There were not enough individual respondents by country for Daoust to compare each nation, though he did confirm that the lack of differences by age wasn't driven by reluctant elders in just a few countries — the phenomenon appears similar in all countries surveyed.

There could be many reasons that older people aren't more likely than younger to take precautions, Daoust said. They may be less comfortable with technology that would allow them to socialize without meeting face-to-face, he said. Or perhaps the oldest age groups view risk differently. After the paper was published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on July 2, Daoust received an email from a reader who was over 70. The person said that at that age, death feels inevitable. It's not that older people want to die, the reader wrote, but the danger of the virus seems less relevant.

For those who hope to convince an older loved one to take precautions, Daoust said his political participation work might provide some advice. Older people are more likely than younger people to view voting as a duty, he said. It's possible that appealing to that same sense of duty might help persuade older people to be careful to avoid coronavirus, he said.

"I would make the following parallel: How is it that you voted in most of the elections in your life, if not always, because you see it as a duty, part of a collective action, but that you do not see your current behavior as an important duty to protect yourself and others?" Daoust said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.